Why Must Literacy Be Reframed?

By: Gene M. Kerns, Ed.D.

Imagine, in a year devoid of major financial market disruption, that you dutifully invested twice the amount you did the previous year into your retirement account, only to see that your account balance remained the same at year’s end. You doubled down on your investment strategy, yet it made no difference. How long would you continue that approach?

Or imagine working overtime only to find that your paycheck remained flat. Would you question the extra time you put in? Of course you would. Would you work overtime the following week? Probably not.

As educators, we want to know that our investments of time, energy, and resources pay reasonable dividends for our students. Well, it’s time for us to be honest and admit that we have a major literacy problem in the US: we have expended vast amounts of resources and have little to show for it. It appears that elements of our current approach to literacy are deeply flawed, yet we continue to make huge investments that yield little to no return.

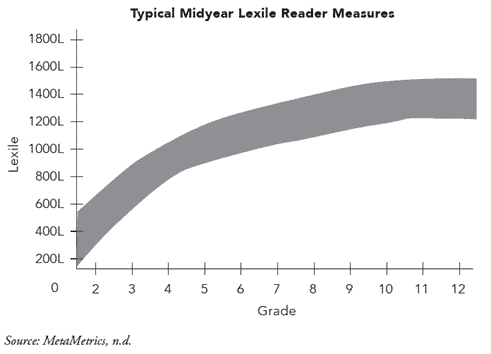

So, what is the literacy challenge we face? Succinctly stated, it’s stunted reading growth for students after the late elementary years. One of the most commonly used measures of text complexity, which is used to evaluate both the difficulty of books and the reading abilities of students on the same scale, is the Lexile Framework created by MetaMetrics. The graph below depicts typical midyear Lexile measures across grades 2–12 for US students who range in performance from the 25th to the 75th percentile. In other words, this figure illustrates how a vast number of our students grow in terms of literacy.

What we see is consistent growth in the early grades that then levels off quite substantially in the later grades. To some degree, this is a normal pattern for cognitive development and not necessarily a cause for immediate concern. Students often see very large reading gains in the early years; the difference between a student’s reading skills in grade 1 and his or her reading skills in grade 2 will always be greater than the difference in the student’s reading skills between grades 10–11. That said, it is a sad state of affairs when the difference in ability between grade 7 and grade 12 is negligible. These five additional years of schooling typically do not substantially increase most students’ abilities to engage with more difficult texts.

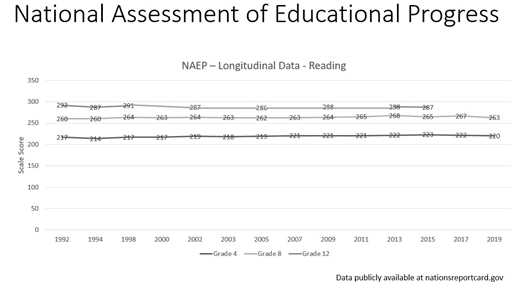

Other data sets reflect this flatlining pattern. The most insightful may be results from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) which document stagnant reading proficiency rates across decades. Unlike state tests that, in most cases, have changed drastically over the past 30 years, the NAEP benchmarks have remained relatively stable, and they depict a grim picture of abject flatlines.

Similarly, in most states, the highest rates of proficiency occur on grade 3 reading tests. Fewer students are then proficient by the end of grade 5, and still fewer in grade 8 and grade 10. Over the years of school, proficiency rates drop considerably, and the gap between the highest- and lowest-performing readers gets wider. On some level, many educators have recognized this pattern, and sadly—whether consciously or unconsciously—they have, in essence, accepted it.

There is another piece of this flatlining story that we must also acknowledge. When No Child Left Behind was enacted in 2001, many schools reacted by cutting time devoted to science, social studies, and anything other than ELA and mathematics in order to increase time for the assessed areas of ELA and mathematics. McMurrer (2007) notes there was a “47 percent reduction in-class time devoted to subjects beyond math and reading” (cited in Hirsch, 2017). By increasing our efforts in the name of literacy and by allocating nearly twice as much time for its study, did we see any substantive changes in students’ proficiency? No. And this reality should cause us to re-examine everything.

Continually stagnant rates of proficiency—even after many schools substantially increased the time devoted to ELA—clearly tell us that the way we are currently addressing literacy simply is not paying adequate dividends. E.D. Hirsch (2017) suggests that our current approach must be a “misconceived scheme,” because “the ‘accountability’ principles based on [it] have not induced real progress in higher-level reading competence.”

This brings to mind the familiar definition of insanity often attributed to Albert Einstein but actually written by novelist Rita Mae Brown—doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. The “reading wars” debate about the best way to teach reading (whole language versus phonics) did not help, nor did the billions of dollars in spending authorized through Reading First, nor did the major reallocation of our most precious resource, time. All of this indicates that we are in desperate need of new insights around literacy. Our current approaches simply are not paying adequate dividends.

Researchers Jared Myracle, Brian Kingsley, and Robin McClellan (2019) conclude, “Alarm bells are ringing—as they should be—because we’ve gotten some big things wrong: Research has documented what works to get kids to read, yet those evidence-based reading practices appear to be missing from most classrooms.” So, how do we bring real change to an enormous and often deeply entrenched institution like K–12 education? In our new book, Literacy Reframed, my co-authors and I explore elements of the solution. Some of the most important aspects include:

- New insights from cognitive science that help us to critically re-think our teaching practices.

- How vast amounts of vocabulary can be efficiently acquired.

- The critical and often underappreciated role of knowledge in reading comprehension.

- The symbiotic relationship between reading and writing.

- What we know and still need to learn about reading digitally.

While there are still many things to be learned and many discussions to be had, the good news is that there are some relatively simple things that we can do that will drastically improve student performance. It’s time for our hard work and investments to pay adequate dividends. It’s time for literacy to be reframed.

For more, see:

- Teaching Through Change, Stories of Resilience: Austin ISD

- Hybrid Instruction Creates More Time for Formative Assessments

- Why Mentorship Matters

Gene M. Kerns, Ed.D. is the Vice President and Chief Academic Officer at Renaissance.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

References

Hirsch, E.D. (2017). Why knowledge matters: Rescuing our children from failed education theories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Educational Press.

Myracle, J., Kingsley, B., & McClellan, R. (2019). We have a national reading crisis. Retrieved from: www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2019/03/07/we-have-a-national-reading-crisis.html

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.