How to Innovate Without Getting Fired

The board of a struggling school district hires a new superintendent to make things better.

A new independent school head joins a community successful by traditional measures but with a board that thinks the school could be more relevant.

In both cases, a school administrator could rush into making big changes and find a lot of resistance, make a few missteps, lose support and get fired before their agenda really takes hold.

Before digging into the question of how to innovate without getting fired, it’s worth differentiating between improvement (doing things better) and innovation (doing things differently), hoping for big gains in old measures and/or new outcomes.

Compared to improvement, innovation is more difficult, involves more risk, and may take more investment. As a result, it usually requires broader agreements.

For educators itching to innovate, there are five tips that will build support and mitigate risk. They may slow you down initially, but it’s a case of go slow to go fast.

1. Update your personal vision. The first step is to make sure your personal conception of what young people should learn and how they should learn it is current. There are at least four topics you and your leadership team should consider in shaping your learner experience vision:

- Learning science developments suggest that effort, failure, and reflection yield growth. Digital Promise has organized learner variability resources that help teacher teams match strategies for every learner.

- The future of work is being driven by artificial intelligence and exponential technologies that are reshaping every sector. Novelty and complexity require leadership and design skills.

- The global shift to competency includes personalized pathways and supports and authentic demonstrations of learning.

- The evolving postsecondary landscape includes new pathways to employment and contribution that start in high school.

2. Build political capital. Hard work requires political capital. Think of your ability to act as a bank account. There are three ways to make deposits in your political capital bank account:

- Personal deposits: showing empathy, demonstrating reliability, showing up, saying thank you, and celebrating progress.

- Community deposits: building support with the board, parents, business partners, and community leaders.

- Resource deposits: delivering new supports, resources and partnerships.

Withdrawals include changing routines, adding demands, terminations, making mistakes, and anything that feels like draining resources.

A negative balance in your political capital bank account means you’re fired (or at least, at risk of it).

3. Facilitate a shared vision. Invite staff and community into a conversation about what’s happening in the world, what graduates should know and be able to do, and the kinds of experiences likely to produce priority outcomes.

In a dynamic environment, education leaders must be skilled conversation hosts and agreement facilitators. The first step in building a shared vision is to build agreement on the profile of a graduate. It should identify priority learning outcomes while leaving room for multiple pathways to community contribution.

With clear aims, the conversation shifts to productive learning experiences. Visiting good schools is a great form of learning for staff and community members—traveling and studying creates an expanded and shared sense of what is possible.

These community conversations help education leaders to gauge the interests and risk profiles of stakeholder groups and the appetite for better or different.

It’s worth acknowledging the personal tension created by developing a compelling personal vision (no. 1) and the listening and facilitating required in order to build a shared vision. While ed leaders should use every opportunity to share their personal learnings and convictions, building a shared vision is a community agreement around a shared future state.

4. Build a frame. More than a vision but less than a step-by-step plan, a framework brings a vision to life with shared values, design principles, tools and supports. Invite and support teacher teams to grow into the frame and (just like personalized learning for students) support unique pathways.

We’ve seen this approach used successfully in many school districts, including Albemarle County, Cajon Valley, Dallas, El Paso, Salisbury, Lindsay, Loudoun County, and Windsor Locks.

From leading districts, we’ve learned four lessons about this approach:

- Distribute leadership: identify teacher leaders and expand leadership opportunities. Attack problems with teams.

- Pilot future environments: illustrate the future with model classrooms and microschools.

- Start small, iterate up: work from the edges in, using available entry points.

- Build fast and slow lane support: allow teacher teams and schools to move at their own pace (but put the vision on a timeline to guarantee equitable access).

5. Share progress. Build a dashboard of metrics important to stakeholders and report out as often as possible. Eric Ban from Dallas County Promise sends out a data-rich email every week celebrating progress.

Find ways to measure what matters. Make sure the dashboard reflects the portrait of a graduate as well as responsiveness to stakeholders.

Invite students to share presentations of learning to public audiences at least twice a year. Encourage them to build a portfolio of personal bests. Create learner profiles and extended transcripts that help learners share their capabilities.

Not only does St. Vrain Valley Schools (@SVVSD) do a great job of sharing their progress, they tell the good news of public education in Colorado through Our Schools Our Community and @COSchoolsProud.

If you develop your personal vision, build trust and support, facilitate a shared vision, invite teacher teams to grow into a frame, and share progress you’ll have a long career of innovating for equity.

For more, see:

- 10 Turning Points: Why It’s Time to Lean Into The Opportunity of the Innovation Age

- 10 Innovations that Support Students’ Community Contributions

- Advancing Equity Through Innovation: 7 Noteworthy Approaches From Brooklyn LAB

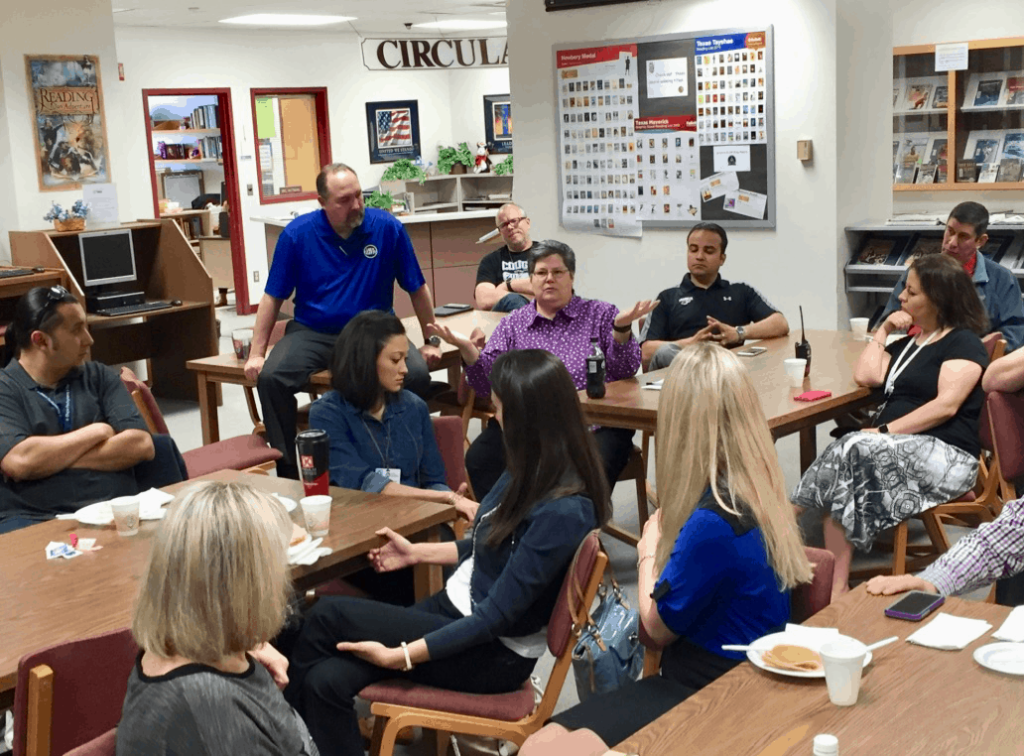

Header image: El Paso superintendent Juan Cabrera talking to teachers at Franklin High

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

This blog was originally published on Forbes.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.