How Design Thinking Transforms Communities, One Project at a Time

Key Points

-

For many, entrenched in an outdated system, what if’s are the stuff of science fiction.

-

Too many structures hold this kind of innovation back- from standardized tests, to grades, to unwavering curriculum.

-

Design Thinking can transform communities.

By: Kyle Wagner and Maggie Favretti

#Whatif

What if every course began with a single Essential Question?

What if people were rewarded for having ideas and not ownership of them?

What if every student experienced success in solving a community problem?

What if school buildings were leveraged as community centers?

What if success in school was measured based on contribution to your community, rather than rote knowledge?

What if every learner could co-author their learning journey?

These were questions that rose to the surface from educators around the world when given a blank canvas to re-imagine school.

For many, entrenched in an outdated system, they are the stuff of science fiction. Too many structures hold this kind of innovation back- from standardized tests, to grades, to unwavering curriculum.

But for a bold and courageous few, these ‘what ifs’ are a manifesto for immediate action.

Meet Maggie Favretti, founder of ‘DesignEd4Resilience,’ (DE4R) an organization that uses design thinking to facilitate collaborative community responses to climate change and other complex issues.

Maggie has empowered young people to transform these ‘what ifs,’ into ‘what happens when?’

“What happens when young people find a meaningful, healing purpose, and connect with nature and other people to create a more equitable and sustainable world?”

This powerful and provocative question has propelled young people in DesignEd4Resilience to: Develop community disaster plans and co-create logistical centers to respond to devastating hurricanes. Create toolkits and resources for emotional and mental well-being during proliferating pandemics. Build community gardens and shared farming plots to protect from food shortages.

It’s a way to connect us to each other with openness and empathy.

Kyle Wagner and Maggie Favretti

These young people’s canvas is not limited by the four walls that shape traditional schools.

Their canvas is their community.

And the brush they are using to fill it in is design thinking.

Design Ed 4 Resilience version of Community Design Thinking is based on Stanford D-school’s 5-step process and also on the National Equity Project’s Liberatory Design processes. The DE4R 6-step process provides a clear, repeatable framework for addressing challenges and drawing on innate creativity and collaborative courage, from innovation through implementation. Young people and their communities worldwide are using models like this to address problems as existential as climate change, to issues as localized as clean fresh water and food security.

But it’s more than a framework to address community challenges.

It’s a way to build coherence in learning and the capacity to understand issues more complex than our traditional textbooks and fragmented, watered-down curriculum provide.

It’s a way to connect us to each other with openness and empathy. The Design Ed 4 Resilience version of design thinking is set up to co-empower. It begins with belonging and safety and challenges us to notice and address our preconceptions. It calls on us to reflect critically on relationships of power within the process and our communities, to be sure that the authentic power of design (from challenge and opportunity-seeking through problem-solving through decision-making and implementation) is inclusive of youth and more specifically, those voices typically unheard.

You can use the same process in your community.

This article will unpack each step of the design thinking process in the context of real community projects, and provide ideas for how you might use the process in your own classroom and community.

Step 1: Gathering Knowledge; Cultivating the Power of People

Maggie Favretti is a firm believer in ‘zero-based thinking.’ Zero-based thinking asks us to rid ourselves of all preconceived notions, biases and assumptions, and literally start from zero. Assuming we know nothing, what questions might we ask? Only in this way can we build on our empathy and remain open to new ideas and ways of thinking and being.

Maggie prepared young people to embody this empathy-based process when seeking to address the resilience to flooding of a nearby town in Puerto Rico, into which Hurricane Maria had poured her fury.

Using the three mental frameworks of ‘People, Place, and Purpose,’ young people uncovered the nearby town’s greatest concerns and strengths by interviewing community partners:

What does the community value? Where was there visible evidence of these values?

Where was there evidence of community resilience? How did the community develop this resilience?

What impact did disaster and climate change have on mental and emotional health?

What else contributed to this trauma and sense of unease?

What are their biggest fears/ areas of concern, and what do they identify as strengths?

Through countless interviews, phone calls and observations, young people uncovered four major areas of concern: flood and earthquake-proof housing, better evacuation planning, climate recovery and mental health, and overall community resilience.

Building Deep Listening and Relationships In Your Community:

How might you uncover issues and needs in your community? Who are prominent members that you might partner with to discover these needs and connect to key stakeholders? Who usually gets left out of those conversations, and how might you partner with them also?

Some Strategies/Ideas:

- Observe, Ask, and Listen, listen, listen. Engage youth and community in recording their own stories and images, using tools like Photovoice. Think of this from the beginning as a shared process, where ‘the designers’ are facilitating community (or student) design.

- Build a shared community map to identify potential needs and assets.

- Attend City Council Meetings and jot down issues being discussed during the open forums, or host community fun events where you are also cultivating participation.

- Look for relevant community organized events via MeetUp.

- Attend local NGO fairs and Outreach events (make sure to cross-reference the NGOs)

- Learn as much as you can, noticing your own assumptions and biases, about the environmental, historical and political context of the community.

- Run a short ‘design challenge’ or mini-project as a warm-up for larger scale prototyping (this can also be done in the first stage of the design process to sustain momentum and increase trust in the process).

Step 2: Defining Perspectives, Challenges, and Opportunities

After uncovering areas of need, to better frame the problem, Maggie worked with her young learners to envision what success might look like for the community had the challenges been addressed. How would life be different with earthquake and flood-proof housing? What changes would they see with a clear and coherent evacuation plan?

Imagining these ‘best case scenarios’ helped students to frame specific problems they hoped to design around. They captured these opportunity statements as ‘how might we’ questions to help guide the design of their solutions.

Identifying Challenges and Opportunities In Your Community:

How might you identify the most pressing community needs? How will you ensure that you have gathered all relevant stakeholder input? How can you make visible the abstract inferences and learnings from your community partners? How can you create a challenge/opportunity statement that will generate rich ideation?

Here are some examples from the Puerto Rico D-Lab:

How might we cultivate community resilience, well-being, and empowerment in our community center?

How might we speed evacuation and ease anxiety around potential flooding and earthquakes?

How might we support mental health recovery without labeling/othering people as mentally ill?

Some Strategies/Ideas:

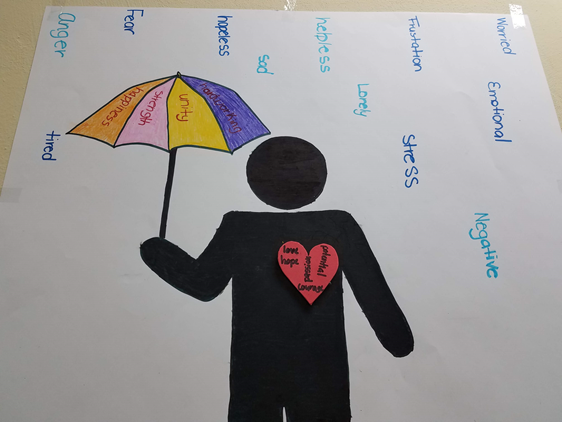

- Make thinking visible, using image-making such as the one above. Create a public event held at a visible community center to share findings and gather more stakeholder input to surface key concerns. Challenge/Opportunity statements can be created and ideated together.

- Connect with global partners who have addressed similar problems.

- Create an advisory board that connects students with their community partners to ensure the fidelity of solutions.

Step 3: Ideating Solutions and ‘Unleashing Creativity’

Our young people are never short of ideas once we remove the shackles that often bind them. During this phase of the design process, we want young people to think divergently. This way of thinking values the quantity of ideas, not the quality. That’s for a later stage. Using the ‘25 ideas in 10 minutes’ challenge, Maggie got some teams to create over 100 ideas around developing flood and earthquake-proof housing.

Other good frameworks for ideation include the ‘Yes, and’ strategy, where one team develops a series of solutions and then passes the sheet to another group to affirm the idea (‘yes’), and add (‘and’) 3 to 5 more of their own. This cross-collaboration between teams helps young people see challenges from fresh perspectives. Maggie also stresses the importance of including community partners in this process:

“Involving community stakeholders in ideation yields trust in the process and helps creative consensus to emerge about what’s possible.”

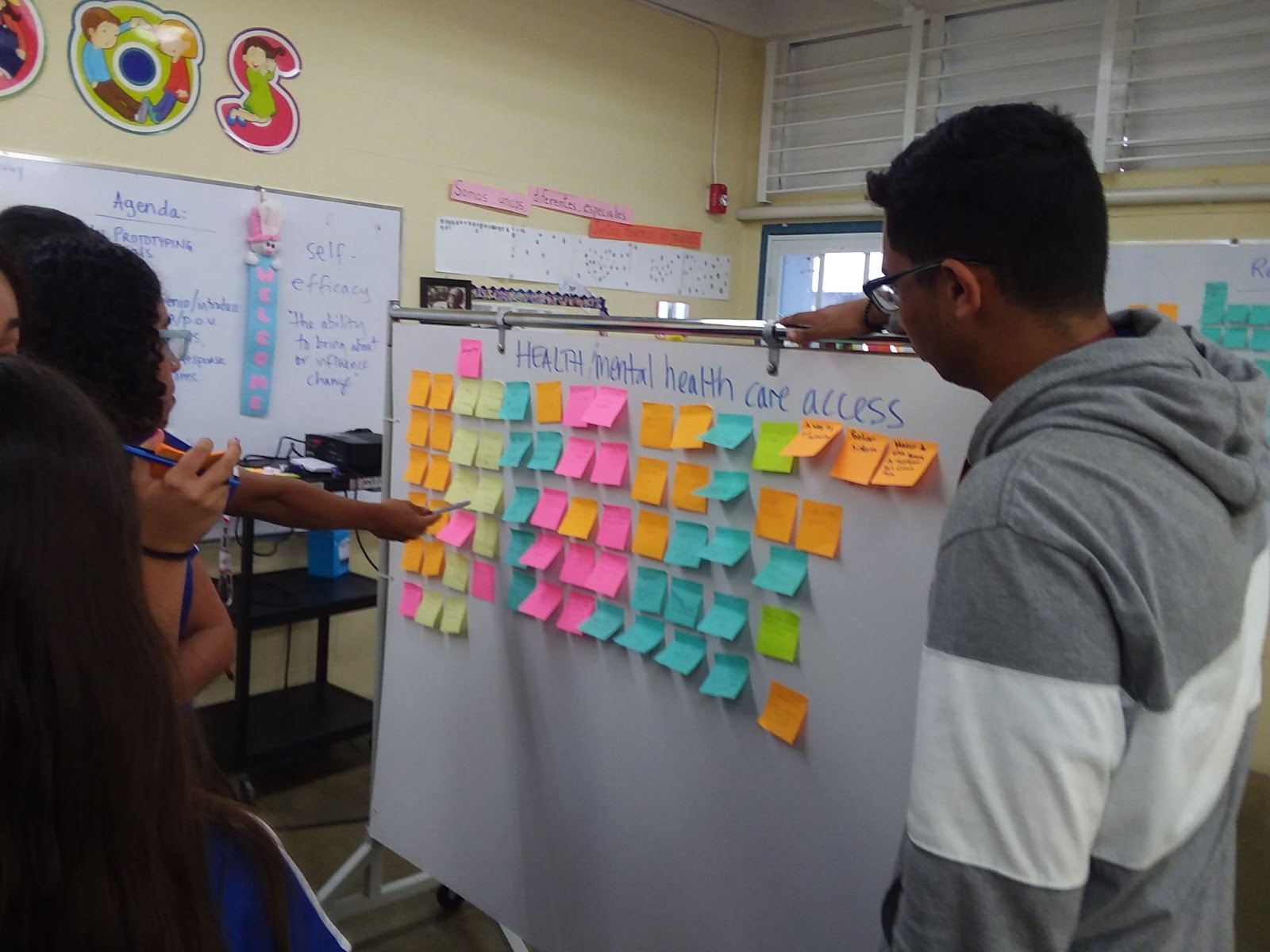

After spending time ideating, it’s time to categorize and connect. Like ideas can be grouped together and be measured against the design constraints and their potential to fulfill the opportunity emerging from key aspects of concern. New questions arise, such as, ‘is this possible? And how will we do this?” The picture below captures this process:

Ideating Solutions to Needs in Your Community

How might you help unleash creativity in your students? How might you group them to generate a number of ideas? How might you facilitate groups to include community partners, and materials for ideation? (post-its, white boards, manipulatives, shapes, gifts, food, etc.)

Some Strategies/Ideas:

- Do warm-up games (like easy improv) before ideation, or do your ideation while running on a treadmill, or on a walk through nature. Research proves it works! In a classroom, provide opportunities to stand, lean, and move around.

- Have lots of manipulatives to hold, touch, feel and play around with. This helps distract the mind and allows ideas to flow. Many people find art materials, colors, and music inspiring.

- Break into smaller teams, and invite community members to co-ideate to generate more ideas and deepen trust.

- Develop a design brief around the specific problem that captures research, insights, timelines and key deliverables.

Step 4: ‘Rapid Prototyping’ Bold Ideas

There’s a prevailing thought in the education world, that we shouldn’t try something until it’s been researched, analyzed, tested, and weighed in on by experts. The problem with this way of thinking is that by the time all of this takes place, the idea is outdated. Innovation relies on a concept called ‘rapid prototyping.’

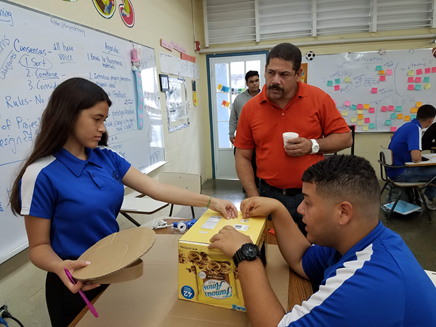

In this phase of the design process, young people in Puerto Rico constructed models of their solutions using whatever materials were available. Cardboard, legos, scrap paper, and recycled materials– ‘clean garbage.’ The goal here is not perfection, but simply a prototype that can easily demonstrate the idea in action.

As young people constructed their prototypes, Maggie asked students to “brainstorm what kind of expertise their ideas would require to fully build,” as well as “community partners who might share knowledge.”

Below are students seeking more expert input about emergency evacuation based on their prototypes:

Building Prototypes:

What materials do you have readily available for prototyping, and how might you demonstrate how to use it? Cardboard, old newspaper, magazines, etc. What expertise do your parents and other community members have that might assist in measuring the feasibility of ideas? How might you share prototypes students build?

Some Strategies/Ideas:

- Gather/upcycle scrap materials for prototyping. Do a cardboard collection!

- Invite parents or community partners with relevant expertise to assist students in their designs.

Step 5: Testing with Real Community Members/Stakeholders

Unfortunately, this is the stage where most projects end. Students dress up nicely and share their prototypes in a public exhibition, and then the prototypes go promptly to the place most projects wind up; the dumpster.

Not in Maggie’s Design4Resilience Program. She understands that the impact on youth self-efficacy and confidence of this repeated message that ‘your ideas don’t actually matter’ is strongly felt and ripples back through the community. DE4R Design Thinking also has an Enact step, which is where collaborative leadership, entrepreneurship, and civic agency takes root.

“At this point, we invite back our community partners and potential funders and present to them.”

Unlike a science fair where ribbons are awarded, prototypes are actually advanced into the ‘development phase’ to be enacted in the real world.

The student projects opened the door to a mobile mental health clinic that was actually a makerspace and funspace, an ongoing relationship between a UPR architecture class and the community, a new evacuation map and an agreement with the PRDE to unlock the school located on the highest ground in anticipation of flooding, an evacuation/emergency plan for their school, and plans for resilient community hubs such as the one being shown below. The programming framework for it created by the students got published and is being used throughout the Puerto Rican archipelago and beyond.

Developing and Enacting Ideas:

What potential funding might exist for student ideas? Are there incubators in your community that hold ‘startup’ competitions for new ideas? How might you connect with them? Are there high-tech design labs that exist in the community to build prototypes? Are there engineering students or university partners who can offer expertise in the development phase? What ‘low-tech’ maker partners can help create scale model working prototypes? Who can build it and maintain it? What community allies do you need to advocate with in order to enact the project?

Some Strategies/Ideas:

- Use Feedback Protocols to help stakeholders provide feedback on each proposed prototype.

- Partner with a university, a Fabrication or Design Lab in the community to help build out prototypes and develop ideas.

- Hold ‘Pitch Events’ for students to pitch ideas to potential funders or investors (with any profit generated going back into the community).

The TRANSFORMATIONS

Critics of design thinking might assume that this process is generally reserved for rich kids, in elite private school settings. But that’s the magic of the framework. Looking at it with a critical lens helps to make it work for young people of all backgrounds, socio-economic classes, and cultures.

Maggie’s students, many of whom come from less privileged backgrounds in Puerto Rico, were transformed by the experience. Using Likert Scales, students reported an increased sense of self-efficacy, deeper knowledge of climate change, and positive feelings towards schools as a result of the experience. Most importantly, they felt a renewed sense of optimism for the future. One student said, “After the storms, all I could do was draw. I just drew and drew. Design Lab gave me my voice back. Now I know I have ideas that can help.”

Turning OUR ‘What Ifs’ into ‘What Happens When’

What’s holding you back from innovating on your campus? Yes, it would be nice to re-make the master timetable, rigid curriculum standards, and mandated state testing; but those are things many of us have little control over. Most of us do however have control over how we organize learning experiences. Rather than start from a textbook, try starting your next learning experience from a community need.

In this way, you will no longer have ‘what ifs’ but rather, ‘what happens when?!’

Want to dip your toes into the design process? Joining the Design Thinking Hackathon Wednesday, October 27th where we will hack the process of effective project design by designing creative solutions around teacher well-being!

Maggie Favretti, a Yale-and Middlebury-educated cultural historian, has spent 35 years happily helping her students to ask, “why not now?” She is the author of the new book Learning in the Age of Climate Disaster: Teacher and Student Empowerment Beyond Futurephobia. Maggie has won scholarship and teaching awards from three professional historical organizations (WHA, AHA, OAH), a national organization of bankers (Sallie Mae Foundation Teacher of the Year), and a national organization of student leaders (21st-century Teacher of the Year).

Joy Favretti

Full of great ideas! and good "out-of-the box" thinking so relevant for solving todays problems

Mara Simmons

Fabulous on so many levels! 1) I am a HUGE fan of design thinking and it combined with PBL. 2) Currently I am in Puerto Rico and am encouraged to find out more about the results of this project. 3) I am in the process of planning a project for a school I am working with in Abuja and can’t wait to use this write up as a framework to help the teachers consider this approach to designing future projects… THANK YOU!