On Spreading Learning Innovations: Pandemic Update

This is an update to a 2017 post.

Expanding access to valuable learning experiences is one of the most important change forces for good, potentially rivaling cleantech, biotech and democracy for the potential to promote peace and prosperity on planet Earth.

But, as noted in Smart Cities, we don’t know much about how these learning innovations are created and spread—what social scientists call innovation diffusion. Developing new ways to scale quality will be as important as new approaches to learning. Why is scaled innovation and improvement so challenging in education? Learning is a complicated mixture of influences of formal institutions and informal experiences. Very simply, learning (or, more broadly, youth development) is a function of the public delivery system, family and cultural transmission and self-directed activities.

It takes a village, or more precisely (as we’ll discuss below), it takes an ecosystem. For this discussion, let’s focus on schools. It’s not that we don’t know how to create schools that work for nearly all kids–there are great examples all over the country. We don’t seem to know how to get out of the box we’ve created. We don’t know how to untie the Gordian Knot of federal, state and local policies intertwined with employment agreements that would allow quality at scale. Adding to the gravity (just to add a third metaphor) is our collective and idealized memory of school–grade levels and report cards, courses and credits, some kids get it and some don’t, and summers off.

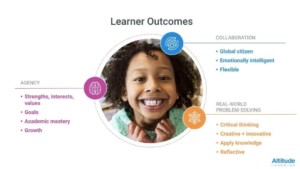

About experiences that promote deeper learning competencies (critical thinking, collaboration, communication and learning how to learn), the Hewlett Foundation summarized the challenge in three parts:

- Systemic Problem: Much of the system that has accumulated over the last hundred years mitigates against deeper learning experiences and fixing that is big technical, political and economic challenge.

- Equity Problem: You could observe deeper learning in many schools but it’s traditionally underserved students who are the least likely to experience deeper learning.

- Dosage Problem: Many teachers are deploying deeper learning strategies but it’s not clear that it is insufficient frequency and quality to produce desired outcomes.

The pandemic related shift to learning at home in the spring of 2020 highlighted all three of these problems. It rocketed the adoption of video conferencing from nothing to widespread use in a matter of days but with big differences in access and quality of usage.

The schools that made successful transition to remote learning were most typically located in districts with a ten year track record of building equitable infrastructure and supporting commonly used learning models. Many were located in states that had proactively supported equitable infrastructure and new learning models. The big districts of Florida like Dade and Broward County benefited from strong sustained local leadership in a state that has supported digital learning for 15 years.

To summarize this introduction:

- Youth development is a complicated mixture of influences including family, school and community.

- We’re beginning to better understand the knowledge, skills and dispositions most important to civic and career success, but a small percentage of youth have access to experiences that promote those outcomes.

- We know how to create good schools that promote these next-gen outcomes but we know less about doing it at scale–particularly where it’s needed most. Sustained and effective local leadership and a supportive state context appear to be critical.

Let’s begin by exploring why education is prone to fads but resistant to systemic change.

Scaled Impact

There are three change models that correlate with grain size: an easy to adopt practice or tool; a package of tools and practices; and reframing the whole ball game.

1. Practice: New practice, product or tools that require minimal behavior change. Like a sales transaction, these are well defined, easy to deploy and may or may not result in sustained use. A compelling proposition (often free/cheap) with little or no permission required promotes viral adoption. Examples include:

- Tools: Google apps in education (100 million users); ClassDojo (95% of U.S. K-8 schools), and now Zoom video conferencing.

- Practices: Behavior management tactics, learning in stations, projects, maker or coding unit.

Adoption of a product or practice often follows the Rogers curve (below). Innovators, who create or adopt early innovations, approach their work with an innovation mindset. Early adopters and the early majority may require an observation or experience to give it a go (and this is important as adopters at different stages have different mindsets and may require different pitches).

Use of a practice or product may be reinforced by promising early results, positive feedback other users, and the beginning of a community of practice.

2. Package: An innovation that involves a combination of tools and practices like blended and personalized learning that requires new tools and behaviors. A new opportunity (computers in the classroom) or compelling proposition inspires innovators that create new learning models–a combination of aims, practices, assessments and tools.

A package innovation is usually developed by a team (where an adopted practice/product is often an individual act). Teams may want to test their bundle of tools and practices by running a pilot. For a decade, the 4.0 Schools fellowships have been training educators to run iterative pilots.

A whole school model is created by adding to a learning model structure, schedule, staffing, systems and supports. This design work may be grant supported (e.g., NSVF grants, Raise Your Hand Texas grants, Walton Innovative Schools grants).

Developing or adopting a package innovation is much harder than a practice. It’s usually a team sport and often requires some investment (e.g., learning experiences for teachers, computers for all students). It’s what Bror Saxberg calls learning engineering–designing new models by applying good learning science and gathering evidence at scale.

A package of innovations may require permission or waivers, and barriers to development or adoption may include:

- Resources: Budget, systems, limitation of tools

- Permission: Agreement of colleagues and supervisor

- Legal: Contracts, local, state and federal policies

The widespread adoption of an innovation package may be encouraged by public investment (e.g., Ohio Straight A Fund), policy supports or barrier reduction, or networks that bundle components such as a school model, platform and professional learning experiences (below). These like-minded schools may be organized as managed networks (e.g., Achievement First, Aspire, Harmony) or voluntary networks (e.g., EL Education, ConnectEd, New Tech Network) as detailed in our 2018 book on school networks, Better Together.

Platform networks (whether districts, networks, or charter management organizations) that shared school models, tools, and professional learning experiences (illustrated above) were able to make effective transitions to remote learning–especially those with a strong culture of trust, respect and agility.

Platform networks (whether districts, networks, or charter management organizations) that shared school models, tools, and professional learning experiences (illustrated above) were able to make effective transitions to remote learning–especially those with a strong culture of trust, respect and agility.

3. Frame: A new way of framing delivery or a new framework of policies that change the rules of the game. NCLB reframed the last 25 years of U.S. education around standards, assessments and accountability. Regional efforts to reframe the system include the Great Schools Partnership’s work in New England to create school, policy and HigherEd support for proficiency-based learning (read more in this CompetencyWorks series).

Lobbying for a new policy frame can be a super efficient change strategy–one new law and it impacts everyone in a state or the whole country. The problem is that it’s hard to legislate good practice and, as we saw with NCLB, new frames can come with a whole set of unintended consequences.

Given the PTSD of NCLB, a new federal frame is unlikely for the next few decades. But the pandemic halted state testing for a year or two and created a new opportunity for new state frameworks to emerge–one that makes effective use of formative assessments. States will stop mandating week long standardized tests when it is easier to combine multiple forms of formative assessment in valid and comparable ways. New frameworks will consider growth as well as proficiency in basic skills and will also incorporate broader outcomes.

To summarize these observations about scaled impact:

- If you want to get at the systemic problem, the equity problem and the dosage problem, random adoption of products and practices won’t do–it takes new learning models that are a bundle of tools and strategies developed or adopted by teams or systems.

- Development of these innovation bundles is really complicated at this stage so progress is likely to be lumpy and context specific–not a smooth Rogers curve.

- The pandemic transition to remote learning illustrated the benefits of platform networks (with shared goals, tools, and PD). Tens of thousands of schools will be joining platform networks this summer in preparation for reopening in the fall of 2020.

Before we dismiss the old Roger’s adoption curve, let’s unpack how it’s supposed to work and how smart people have built on the model.

Innovation Diffusion

Theories of how change happens in the social sector consider demand, the attributes of innovation, the complexity of change and how it impacts people–the specific behavior change required.

1. Demand. This is how people discover and come to desire the product or practice and the role of communication and decision making, particularly among those rogue innovators. The Rogers curve (above) suggests that innovation is spread from five adopter categories: innovators to early adopters to early majority and late majority, and finally those pesky laggards. The five stages of the adoption process are knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation and confirmation.

Let’s apply this to the grain size analysis above. It’s easy to communicate demand for a specific product, say Pokemon Go–just download and play. It’s harder for a package innovation like personalized learning where there are competing definitions, multiple dimensions and lots of contributing components. The potential benefits of personalized learning must be higher than the apparent complexity and difficulty of assembling and implementing the package innovation.

This is where the Rogers model is insufficient–public education is not just seven million individual actors, it’s a complicated network of more than 100,000 schools and 14,000 districts and their constituent communities. The super complexity suggests the need for a more robust model of innovation diffusion (and may explain why a good idea won’t walk across the street in education).

2. Attributes. There are seven main factors (five from Rogers, two recently added by Billions Institute) that influence adoption of an innovation, and each of these factors is at play to a different extent in the five adopter categories mentioned.

- Relative Advantage: The degree to which an innovation is seen as better than the idea, program or product it replaces.

- Compatibility: How consistent the innovation is with the values, experiences and needs of the potential adopters.

- Complexity: How difficult the innovation is to understand and/or use.

- Trialability: The extent to which the innovation can be tested or experimented with before a commitment to adopt is made.

- Observability: The extent to which the innovation provides tangible results.

- Adaptable: The extent to which the innovation can be adapted to a particular context.

- Scalable: The balance between elements scaled easily and those requiring infrastructure (e.g., HR, finance, technology and governance).

Personalized learning, especially aimed at deeper learning competencies, has high advantages but high complexity, low trialability, adaptability and scalability. Given the limited ability to measure broader aims (i.e., mindsets, creativity and collaboration), personalized learning has limited observability.

The big advantage of school networks is that they bundle innovations reducing complexity and boosting adaptability and scalability. They range from lightweight design networks like Future Ready Schools that just require a pledge to a set of principles, all the way to managed networks which ensure classroom by classroom fidelity to a learning model.

As personalized learning platforms get more robust they will make it easier for schools to support sophisticated learning sequences. For example, Cortex, developed by New York nonprofit InnovateEDU and piloted at Brooklyn LAB, is an extensible platform that supports a variety of personalized learning models.

3. Change. Innovation diffusion is a function of the complexity of the system and the ability of incumbents to manage the adoption process. Systems analyst Donella Meadows suggested a dozen leverage points including mindsets, structures, information flows and feedback systems.

Rogers argues that innovation that is complex, ambiguous or unfamiliar will be slow to spread–that all sounds like personalized learning, right? But personalized learning has become the dominant meme in U.S. education despite the fact that we’re at a point of maximum complexity–tools don’t work together, data lacks interoperability and policy and measurement systems remain orthogonal to desired outcomes. As a result, interest in personalized learning is high but models are early and implementation is often weak.

4. Behavior. Innovation that requires behavior change is a much heavier lift than an innovation that reinforces an existing behavior. Roger’s model, proposed in 1962, is most applicable to consumer adoption (and new practices more than stopping behaviors). Rogers (and others) have suggested behavior change is a function of information, motivation and conditions.

Public health studies suggest the process varies depending on the nature and complexity of the innovation, costs and incentives, communication channels and the social context.

A quick dip into diffusion theory suggests that:

- Clarity on desired outcomes, specific experiences that develop those outcomes and agreement on feedback/measurement will speed adoption;

- Better tools that simplify design and adoption of new learning models will speed adoption;

- Networks of schools that share innovation bundles (including clarified outcomes and better tools) appears to be a promising diffusion strategy; and

- Testing leverage points to see what works best with folks in each stage of adoption may be promising.

Ecosystems Matter

Old schools don’t change easily. New schools aren’t developed quickly. Market signals are diffuse. What will transform this sector? Missing from most conversations about innovation diffusion is research on entrepreneurial ecosystems (see this Kauffman report).

In her preface to Smart Cities, Michele Cahill said, “At the heart of an ecosystem for learning is an ability to draw upon the assets of an entire city or community to support students as they grapple with the two primary tasks of adolescence: building competencies and forming their identities.”

The two-year Smart Cities investigation observed islands of improvement (e.g., traditional schools executing at a high level) and new learning models producing strong results in cities large and small nationwide, and there was always evidence of effective and sustained leadership, collaborative partnerships and focused investment.

The study concluded that, given the opportunities and challenges of personalized learning, most regions are missing layers of inspiration, incubation and intermediation in education. Some of these intermediary supports are best provided locally. Others are only periodically accessed and could be regional or national.

| Local Intermediaries | Local, Regional or National |

|

Incubation: Assistance for new models Grants: Develop/adapt new models Conveners: Host edupreneurs Catalyst: Bridge for innovators Harbormaster: Coordinate quality seats Feedback: Personalized learning pilots |

Talent Development: Recruit/develop great talent Tech Support: Select and support tech tools PD: Develop talent Networks: Connect/support like-minded schools Seed: Support EdTech entrepreneurs Design: Support school and EdTech design |

One problem common to most regions is that no one owns the innovation ecosystem. A dozen cities associated with The City Fund have local intermediaries (called harbormasters or quarterbacks) that support new schools to build access to “quality seats” but often not the broader innovation agenda. Learn Launch in Boston is a good emerging example of an innovation catalyst for the region.

There are five primary approaches that regions take to developing and scaling instructional innovations:

- Communications: How to guides and case studies of successful models

- Talent: Professional development around new models

- Tools: Design and invest in EdTech tools and interoperability

- Technical Assistance: Incubate new learning models and support scaling efforts

- Networks: Replicate bundles of powerful learning models

Some regions will do very little to develop EdTech and may rely on homegrown strategies rather than recruit and scale networks. In some regions recruiting talent will be a priority, in others developing local talent will be the right solution. A strategy evolves in each region, sometimes proactively, with contributions from constituent actors. It’s not clear which solution bundle will produce the best long-term results.

Ecosystem research contributes three lessons to the diffusion discussion:

- Complex solutions require a web of support

- Every region needs a learning innovation agenda

- Every region has gaps in their solution map and could use better ecosystem coordination

Finally, advocacy–what is it, why does it matter and where to start?

Advocacy

Advocacy aims to change hearts and minds. Advocacy seeks to shape decisions impacting political, social and economic systems. Advocacy has a view of what’s working and why. Advocacy imagines that the future can be better for more people.

Many school superintendents come to see themselves as chief advocates for their districts–making the case internally and externally with stakeholders for a change agenda. Some campaigns are formal elections that require subtle support, others are district-led campaigns to build teacher or partner support. Education leaders build and spend political capital to support their advocacy agenda.

Lobbying–a case made to power–is advocacy of the most direct sort. It may be called “education” if it doesn’t include a specific request for money or language but it’s still an effort to change heart and minds. Making the case for change requires a compelling vision. It helps to have a track record of success. And it almost always needs to be a sustained drumbeat over what might be years of telling the story.

Two specific forms of advocacy that achieve scaled impact include jointly funded projects and public-private partnerships:

- Jointly Funded Projects. Foundations can lobby the federal government for new programs if they help foot the bill. These jointly funded projects can provide a big return on effort. In 1998, Mott Foundation entered into a public-private partnership with the U.S. Department of Education to support the country’s 21st Century Community Learning Centers. This partnership led to increased funding for the program from $40 million to $1 billion as part of NCLB.

- Public-Private Partnerships. State investment can help bring early innovations to scale. Examples include:

- Inspired by Kaiser Foundation investments Oklahoma has a universal preschool program (despite terribly low funding for K-12).

- The Texas High School project (now Educate Texas), a partnership between the state and two national foundations, resulted in more than 130 high-quality STEM and early college high schools.

- The goal of Computer Science for Rhode Island (CS4RI) is to have computer science taught in every public school by December 201state-sponsoredonsored initiative includes many private partners and sponsors.

- The RAMTEC robotics training program launched in Marion Ohio expanded to sites as a result of an Ohio Straight A grant.

Good work as advocacy. More subtle is work done well and shared broadly. Civic engagement is advocacy. Social service is advocacy. Active citizenship is advocacy.

A school that breaks barriers and extends equity is advocacy–a proof point that provides evidence of a claim. Public work products and community connections are important forms of advocacy for a school.

Advocacy usually focuses on what and why (e.g., all students deserve to be college and career ready) into the early adopter phase, and shifts to why and how through the tipping point (e.g., curriculum programs, guidance strategies).

Joining a network is advocacy. Networks form community–a commitment to learn and improve together. When communities of practice produce favorable working conditions and remarkable life outcomes across hundreds of schools in widely varying conditions–that’s more than a proof point, it’s a movement.

Some advocacy lessons include:

- Good work is advocacy–at least when people hear about it

- Look for analogous scaling strategies that might translate

- Join a network to amplify your work and voice

Diffusion is something that happens to a gas in a vacuum or a fad in a culture, but it doesn’t explain how innovation happens in education. The old Rogers’ model is more appropriate for individual actors adopting new products or practices. Education has layers of context variables that make progress more lumpy, more episodic.

Robust ecosystems create supportive conditions for innovation, but most important are school and system leaders who facilitate agreements among communities of practice. Where leadership exists, innovation can flourish. Where it does not, it is squelched.

For more, see:

- Structures Drive Behavior: Right is Magic, Wrong is Deadly

- How School Networks Work and Why That’s Important

- How to Promote College Readiness: A Washington Case Study

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.