It Takes a Village: Rebuilding Education Opportunities in NOLA

By Rosie Clayton

Over the last decade in New Orleans, it has taken not just a village but a whole community to do so many things: reassemble, rebuild, repair, redesign, reimagine and regain the soul and spirit that I first caught a glimpse of back when I visited in 2008.

This is a hard piece for me to write. While reflecting on my time and experiences last week, I’ve tried to make some sense of these interrelated themes, most of which I have a very limited understanding of. I’m going to focus on the building and defining of new communities in education, but I also want to highlight some of the things I was left questioning and wondering at the end of the week.

Hurricane Katrina was a defining moment in the recent history of New Orleans, leading to manifest changes on all levels including across and within the city’s education system. Pre-Katrina, education provision in the city was deemed to be failing, and outcomes for young people were close to being the worst in the U.S.

The movement toward reform had already begun, but the change was accelerated post-Katrina with the city takeover of all schools, the firing and partial re-employment of teachers, and mass “charterization” (the equivalent of the move towards academization in England) as a means for rapidly improving schools and managing the demographic changes.

There are many people better placed to provide insight and narrative on this than me—for example:

New Schools for New Orleans: On Closures and Restarts

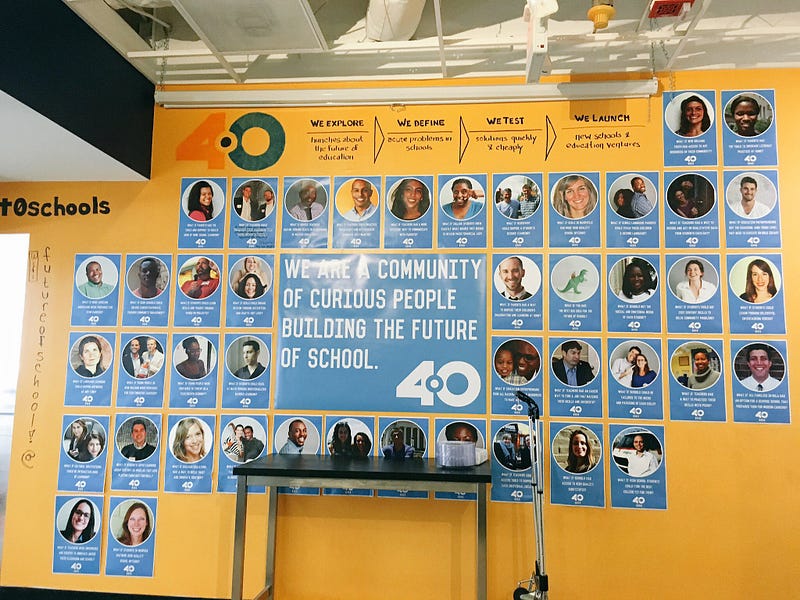

4.0 Schools

System evolution has since moved at a fast pace, driven significantly by the vast numbers of people and organizations from across the U.S. who have gravitated to New Orleans post-Katrina, as well as high levels of capital investment and strategic vision.

I asked Adrien Maught, COO of Rooted School, why there had been such a ‘brain pull’ to a City that at the time resembled a disaster zone, and he described the phenomenon of the Millenial generation seeking and needing a purpose, and wanting to be part of the challenge and effect change.

The city now has a thriving and close-knit innovation ecosystem in education, with its epicenter at the home of 4.0 Schools, which Tom Vander Ark has described as probably the best school innovation and design catalyst in the U.S. 4.0 Schools is one of a number of accelerator and catalyst type organizations which have popped up across the city, a “clustering of capability” developing strong and positive network effects.

These catalysts have a number of important functions within the ecosystem, including (and building on my learning from across the Bay Area):

- Enabling the creation of communities or clusters around issues and challenges — bringing diverse communities together to solve grassroots education issues;

- giving a voice and platform to individuals at the grassroots and a way into the system;

- acting as a talent magnet, drawing together people with an innovation mindset, and framing a collaborative focus on impact;

- constructing and shaping powerful and impactful conversations;

- creating momentum and energy, and collective risk taking (strength in numbers); and

- providing space and time through targeted resource.

4.0 Schools programs provide pathways to innovation on a number of different levels, most powerfully at the very micro level–for example through the Tiny Fellowship, which allows individuals to test their ideas and develop a proof of concept.

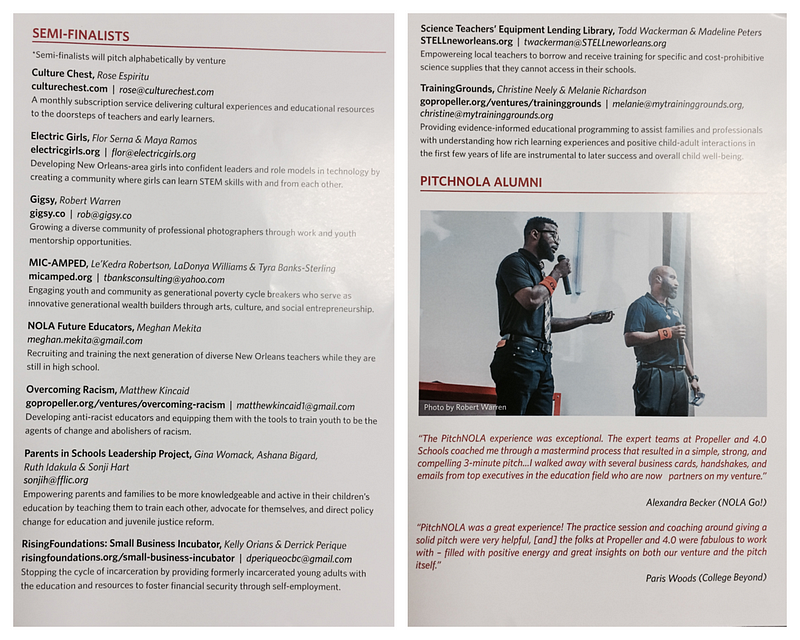

Very excitingly, I was in town for the second annual PitchNOLA Education, a joint 4.0 Schools and Propeller incubator pitching competition, profiling a diverse range of ideas and grassroots-led innovations. Following the competition, the winning projects now have access to other 4.0 or Propeller social innovation programs to further develop their projects or businesses.

As the MC for the evening highlighted, these pitching events have proven to be important platforms for people in the community to “voice insights and genius on the challenges the city faces” around education and youth. And as an audience member later commented, it was great to see the broad community working together to tackle challenges and difference, where politics in many ways is failing and exacerbating such difference.

Since its inception, 4.0 Schools has built a powerful community of edupreneurs, providing the space, structure, insight, capital and networks needed for change making and for leading education innovation thinking across the U.S. in exploring new ideas around prototyping and de-risking innovation. Linked to the points above, its effectiveness is powered by the high density of risk taking individuals and groups that make entrepreneurial pathways the norm rather than the exception.

NOLA Micro Schools

Matt Candler, CEO of 4.0, is an extremely interesting thinker, and one of 4.0’s most recent missions has been around the development of Micro and Tiny Schools. These are schools typically with around 150–250 students, developed through a rapid prototyping innovation model of “pop-up” schools allowing for continual iteration, feedback and flex. Through this model, new ideas can be tested quickly and effectively—leading to lower risk for entrepreneurs and also reduced impact if ineffective.

I spent a day at NOLA Micro Schools, which opened in 2015 and is currently co-located in a renovated market hall. It was co-designed by Matt Candler and Kim Gibson, school principal and another force of nature in the ed-innovation world (and yet another person that moved to New Orleans post-Katrina to be involved in rebuild efforts).

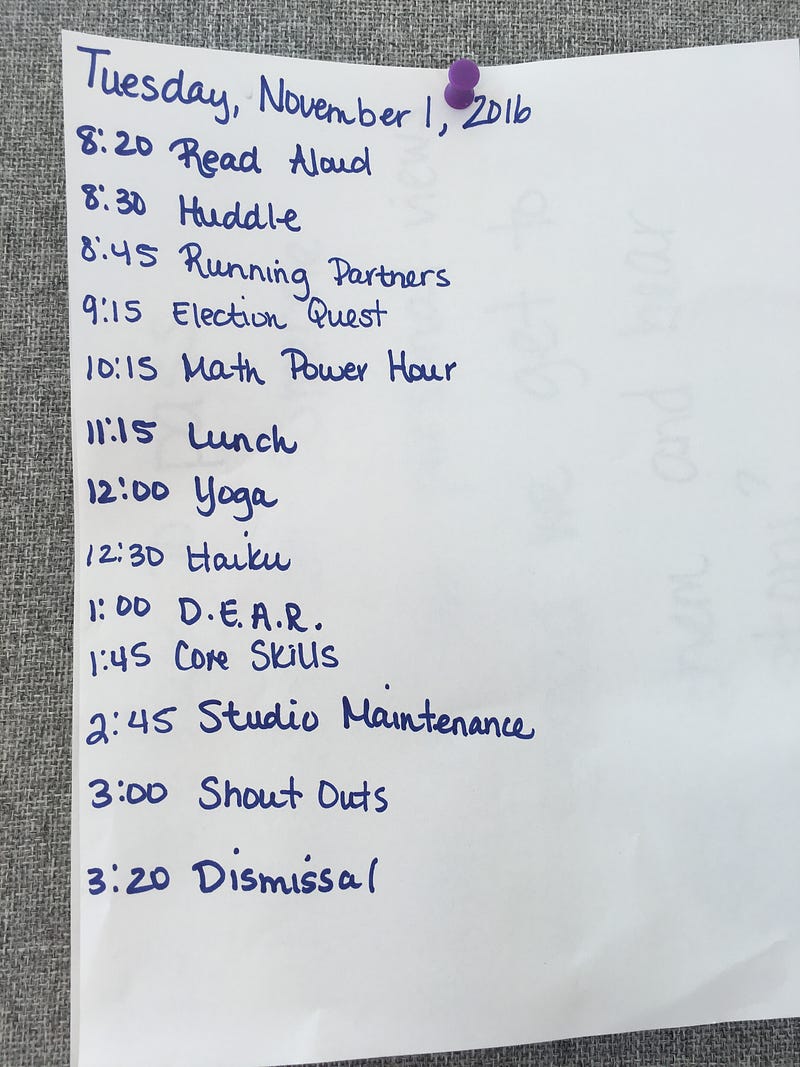

Similar to Big Picture Learning, the school is also very much an “unschool” school in its design, with a focus on student-driven and enabled learning, play and deep inquiry. The school currently has 28 students across two-year groups, and will eventually be an all ages school across four “learning studios.”

A number of things stood out to me during the day as I talked to staff and students about the power of the micro model:

- The strength of relationships across the school community, including relationship dynamics and the range of personalities which enmesh to build a strong community.

- Highly self-directed and also community-directed learning across the school, enabling ongoing balance and flex around autonomy.

- Peer-led and peer-defined personalization. For example, their approach to target setting and assessment is peer-led through a “running buddy” approach, and designed around a challenge wheel where students are constantly pushing themselves outside of their comfort zone. It’s a brilliant tool—simple, personal, and powerful as a tool both for reflective and personal development and for structuring conversations.

- Culture building through shout outs at the end of the day is used to build the value system and interpersonal relationships.

- Their approach to conflict resolution and mediation–allowing “conflicts” to progress either unchallenged or mediated through student debate–was fascinating to watch.

- Tech-driven personalization in its truest sense. They source specific learning platforms for students even at an individual level where necessary, depending on student needs in a particular curriculum area.

I also spent time with the team at Rooted School, a new micro high school which is opening next September and is designed to provide high-level pathways into the tech and digital sector as an alternative to college, addressing acute and emerging skills needs across key employment sectors in New Orleans.

Its curriculum is designed around rapid skill development, with the aim of providing students with the opportunity to access graduate level jobs without the need for a degree. A similar ethos to Make School, but at high school level, and also similar to the Studio School model which I have previously worked on in the U.K.

Micro-schools, and start-up schools in general, have to be agile and resourceful in their nature. Talking to Kim, Jonathan and Adrien, it was clear that they are all highly effective in making connections and leveraging a range of partnerships and resources.

It was particularly impressive to see the way that Kim and her staff team mobilize community assets and resources, from developing multiple learning spaces and opportunities for learning across the city, to drawing on the personal resources of parents and other stakeholders.

For me, it really brought my thinking back to the notion that it takes a village or community to raise a child, and that education should in a sense be the responsibility of a range of stakeholders, not just the teacher in a school building—especially considering that in both the U.K. and U.S., a teacher is regularly a scapegoat for failure or lack of “progress,” and taken to another level in the U.S. through things such as the teacher jail. Drawing on the assets and knowledge of the wider community also recognizes and values the importance of life learning across home, family and friendship settings and cultures.

Poverty and Education

And finally…I feel it’s important to say something briefly on the undercurrents and tensions that I encountered across the city, invariably tied to poverty.

Jonathan told me a heartbreaking story of a young African-American student he had taught whilst a teacher at KIPP. He was on course for a top score in Louisiana State tests and gain a full scholarship to college when he was murdered due to involvement in the drug trade to support his family.

This experience had in part motivated Jonathan to set up Rooted School — as he said to me, “what is the point of an education system that delivers great test results and gets kids into college, but does nothing to address the serial conditions of poverty and life realities of young people. The school community and wider network needs to respond to this too.”

Racial bias in education also regularly came up in conversations during the week, and Jonathan made an extremely interesting point related to his time at KIPP and how their work on growth mindsets in education had been a paradigm shifter around perceptions of African-American underachievement, as well as other destructive narratives related to low-income communities (see the work of Carol Dweck and Angela Duckworth).

It now makes our job as educators and community builders even more vitally important and has magnified the role of schools and education systems in building and bridging communities across all level of societal divides, and in developing understanding between them. Our next generation needs to be equipped to navigate the breakdown of old certainties and enabled to define new ones, to achieve success in life in whatever form that may take, and to have a good standard of living with economic security and opportunity.

The original length version of this blog originally ran on Medium.

For more, see:

- Personalization and Real-World Learning at Big Picture Schools

- An Education Innovation Discussion with Tom Vander Ark

Rosie Clayton is a freelance consultant currently working across education, tech, school and network design in the U.K. She is exploring innovation ecosystems in education across the U.S. as part of a Fellowship with the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust. Follow her on Twitter: @RosieClayton

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.