Portland Youth Exercise Power through Participatory Budgeting

Key Points

-

Young people are completely capable of being involved in work that matters and real-world problems.

-

Intergenerational collaboration is a critical part of democracy.

By: Rebecca Jacobson

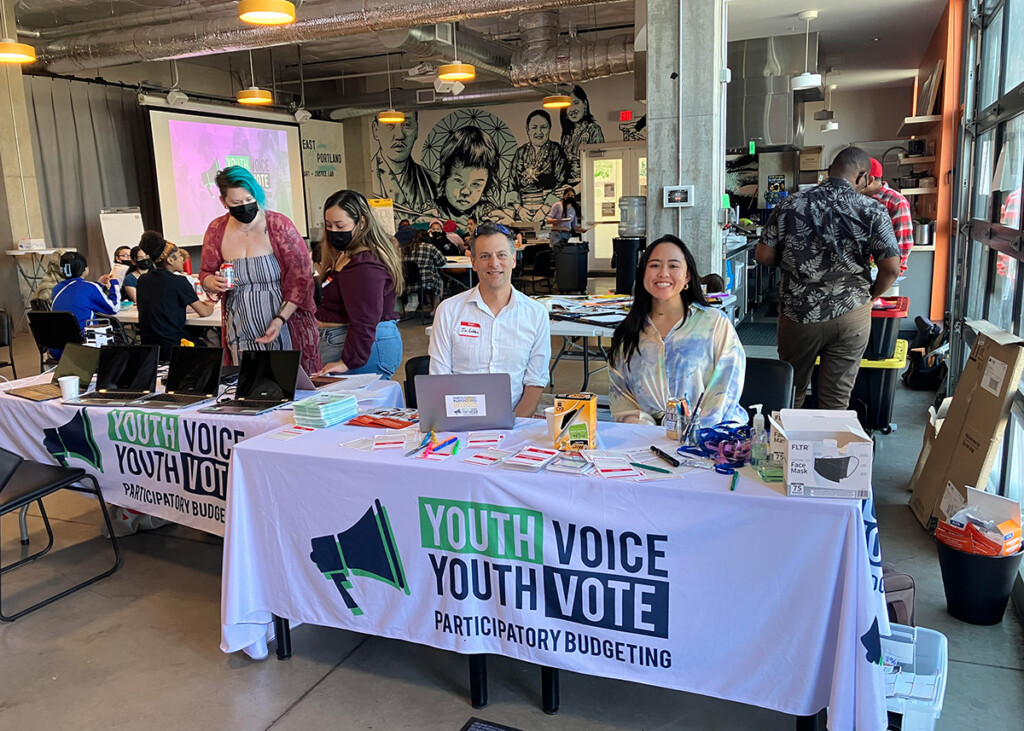

Lillyanne Pham ’20 and Jim Labbe ’95 were part of Oregon’s first-ever experiment in giving community members direct say over how to spend public dollars.

Participatory budgeting, a democratic process in which ordinary people decide how to spend part of a public budget, isn’t a new phenomenon. It was first tried in 1989 in Porto Alegre, Brazil, and has since spread widely; researchers count more than 11,000 initiatives worldwide. But until recently, it had never been implemented in Portland (or anywhere else in Oregon).

Jim, whose career was for many years focused on natural resource conservation, has been engaged in PB efforts in Portland since 2016, and in 2018 helped found a nonprofit called Participatory Budgeting Oregon. In 2022, that organization launched Youth Voice Youth Vote, a program that aimed to enact Oregon’s first-ever PB process. The goal was to engage at least 2,000 youth in Portland’s east metro area to decide how to spend $500,000 allocated by the American Rescue Plan Act.

Why begin with youth? In part, Jim says, it’s precedent: other American cities, including Seattle, Boston, and Phoenix, have carried out successful youth-led PB processes. But it’s also to build a constituency that will be invested in PB over time. “We’re in it for the long haul, which is why we started with a youth-based process,” Jim says. He emphasizes, too, that youth in Portland’s east metro area are a high-need group who represent the racial and ethnic diversity of the region’s future population.

The first step was to hire a paid, all-youth steering committee to design the process and write the rulebook, which is when Lillyanne, an artist and organizer with a focus on place-based and racial equity work, came on board. In addition to being drawn to how PB gives community members a direct say in how public money is spent, Lillyanne was excited by the way this particular program gave the decision-making power to youth (defined here as 13- to 25-year-olds). “I hadn’t known PB could be done totally by youth,” she says. “To have a whole process by youth is crazy cool.”

Process design took place over the summer of 2022, as Lillyanne and 11 other steering commitee members worked to produce a robust plan and timeline. Step two: idea collection, with youth in the project area brainstorming both online and at in-person assemblies about what they wanted to see in their communities. Next, upwards of 100 budget delegates worked in committees alongside community-based organizations to vet and refine ideas into feasible, youth-centered projects.

And last summer, nearly 800 youth took part in a binding vote to determine which projects would receive $100,000 apiece in funding. Voting took place both in person and online, and the winning projects—a job resource fair, a paid two-week program for youth artists, paid internships for youth, expansion of access to menstrual and hygiene products, and improved connections to rental and housing assistance—are entering the implementation phase. Simply put, this means that projects developed by and for young people, and directed at their own communities, are currently being supported by federal dollars.

“The cool thing about PB is that it has different levels of participation,” Jim says. “The steering committee is a deep, deliberative process. With idea collection, anyone can show up and throw out an idea. Budget development again goes deep, and then the voting phase opens up. Unlike a lot of other participatory democracy innovations, PB has both the deep and the broad.”

For Lillyanne, a highlight of the process was witnessing what happens when youth across an age range come together. “It was interesting to see what cross-generational youth collaboration looks like,” she says. As an older youth, Lillyanne felt it important to step back in order to empower her younger peers to trust what they already know and, as she says, to “follow their gut.”

Though efforts to secure funding for a second round of PB have thus far been unsuccessful, Jim remains committed and optimistic. A recent poll found that 72 percent of Portland voters support implementing PB in the city, and 51 percent expressed some or significant interest in participating in a PB process. In a small win, Portland’s recently passed climate investment plan authorizes up to $150,000 per school district for participatory budgeting purposes. While districts aren’t required to implement PB, it’s at least a nod to the process, and comes in part thanks to Youth Voice Youth Vote leaders who pushed to include PB in the plan.

“Part of our goal was to build our capacity and knowledge to do PB, and [to build] the young people’s capacity,” he says. “If PB is going to last, it’s going to have to be from the ground up in a significant way. We’re making youth the experts in a new way of governance.”

This post was originally published in Reed Magazine.

Akhil Sharma

Excellent blog to read very informative