Measuring Learning Growth: Competencies and Standards

Key Points

-

The role of competencies has become increasingly important as employers, students and educators realize the impact of transferable skill deficit in young people.

-

The challenge, however, becomes implementation.

The role of competencies has become increasingly important as employers, students and educators realize the impact of transferable skill deficit in young people. States, networks, districts and schools have begun to accommodate this challenge by building Portraits of Graduate that articulate the need for transferable skills (durable and applicable across many domains). These competencies include leadership, collaboration, communication, etc. and despite many different efforts in this area, there is general consensus about the nature of these competencies.

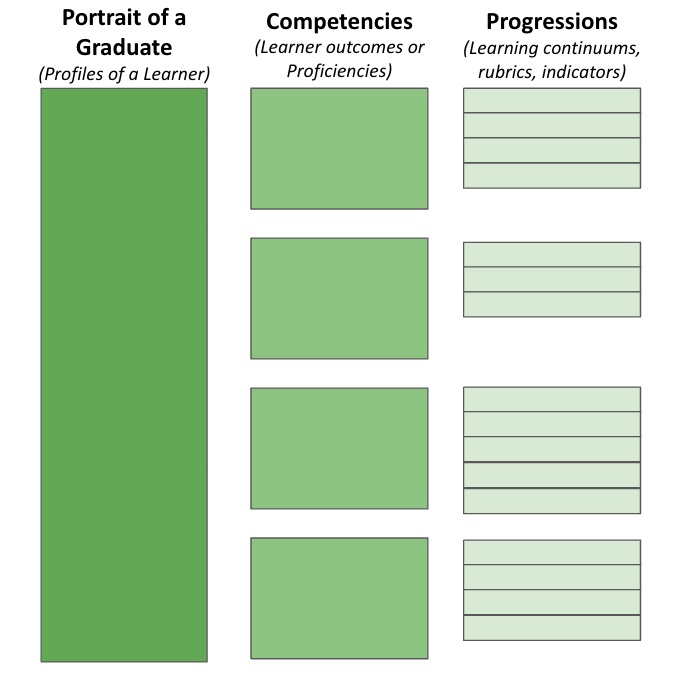

The challenge, however, becomes implementation. With Katie Martin, we highlight the specific steps to take the Portrait of a Graduate into reality. Nomenclature can be confusing here, so for clarity, we define some overlapping terms. A Portrait of a Graduate (also called a Profile of a Learner, Learner Outcomes, Profile of a Graduate, etc.) consists of a set of competencies (also called outcomes, proficiencies, etc.). Competencies are broken down into progressions (also called indicators, rubrics, etc.) that describe multiple levels of proficiency on each competency. Most progressions articulate a level of competency that is expected of learners prior to earning a credential (such as a diploma).

These competencies can be:

- core: high-level skills in core academic areas such as written communication, mathematical thinking, etc.

- technical: high-level skills specific to a particular sector, often CTE related, and

- transferable: transferable across multiple sectors often built into the Portrait of a Graduate)

Regardless of the type, competencies are broad assertions that a learner can apply a particular set of skills across multiple situations with varied contexts.

Learners that can demonstrate these competencies are better equipped both personally and professionally as adults. And, the one question we continue to get is how to specifically assess competencies once a progression of indicators has been built out for each competency?

Traditional standardized assessments often are accurate but not valid measures of a learner’s potential. When assessing deeper learning and application, there are multiple methods to assess a competency. With these types of assessments, it is challenging for measures of assessment to be both valid (correctly measuring what you want to measure) and accurate (being consistent in what you measure).

Standards-based

While standards-based is not competency-based, it is certainly related and worth explaining. The main difference lies in the granularity of a standard (very specific) compared to the more broad skill applications described in competencies. All public schools are required to design curriculum that aligns to state-mandated standards. Some schools explicitly connect all learning, especially in math and literacy, to standards. Most primary schools are now using standards-based report cards with students where each class articulates student proficiency on a set of standards for that class. These standards are evaluated using rubrics that can describe three to four levels of performance where the third level is often deemed “proficient” and the fourth level is deemed “exceeding/extending/applying”.

Dr. Robert Marzano has extended standards-based work to help schools build Proficiency Scales for each standard. These scales articulate the content and skills expectations leading up to and exceeding the standard. This assessment rubric shows performance on the skills/expectations of the level of proficiency. Portage High School in Indiana articulates proficiency scales around each standard, as an example.

Competency-based

Competencies are larger grain size compared to standards, and are transferable across multiple domains, supporting relevancy and useinto the future. Often, competencies are evaluated via performance assessments, complex applied tasks to demonstrate understanding of the competency in multiple and novel contexts. Stanford University’s SCALE initiative offers a database of performance assessments. In competency-based assessment systems three approaches have emerged in the landscape.

Rubric-based competency systems are often found in secondary schools and use the levels of performance articulated in the progression as a rubric. Students submit and re-submit work until they get to a proficient performance level, typically a three. Levels 1-2 show progress along the way, but these lower performance levels are meant to guide the student not serve as levels of attainment. Once a student has submitted enough evidence against level 3, then they could challenge themselves to the exceeding or level 4 performance. In this system, students are submitting and resubmitting until they receive a 3 or 4 on multiple artifacts. At that point, the student has demonstrated proficiency on the competency. Northern Cass in North Dakota uses this system)

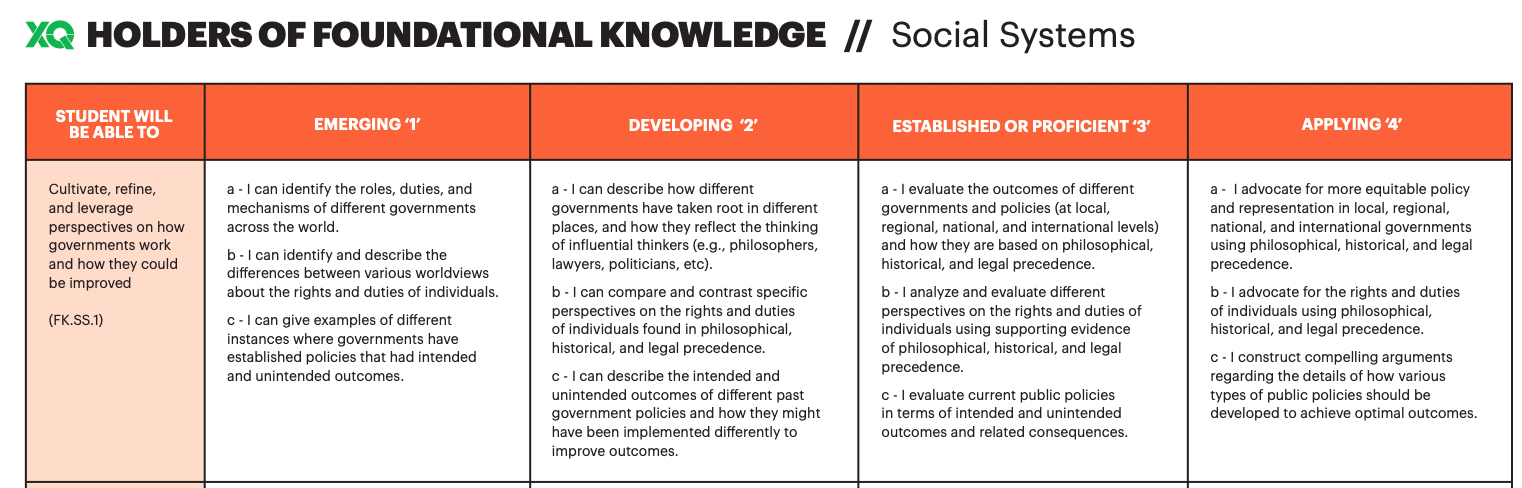

Progression-based competency systems are different. A progression may be a series of levels, depending on whether this is a PK-Graduate system or a secondary approach only, and a student is expected to demonstrate proficiency at one level before moving onto another level. This progression based system implies that a student will demonstrate evidence toward each level. Summit Learning’s Cognitive Skills, Building21’s Competency Continuum, and XQ Competencies are all built on this system.

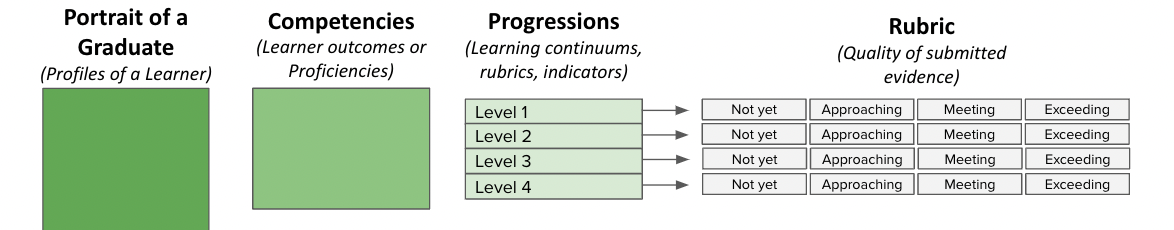

Rubric/progression-hybrid competency systems articulate a progression of indicators for each competency and articulate assessment rubrics for each level of performance. This approach is complex in terms of construction, but provides clarity on each indicator for both the learner and the educator. Specifically, for any given indicator, the evidence submitted is evaluated against the rubric to assess the quality of the submission.

Determination of proficiency threshold

Once a school has a set of competencies, a related progression and has made a decision around how the progression will be used, a series of protocols on how to determine proficiency must be made. Often these protocols are dependent on a teacher who is assessing the artifacts submitted toward the particular competency. Some competencies may only require one artifact while others may require more. Some schools may decide to use a mathematical determination if they are applying a rubric-based competency system. The average of the last three scores, the highest scores, or a decaying average all are methods to determine proficiency on a competency (these calculations are also used in standards-based systems). Some LMS platforms will provide these options (or allow a school to build its own custom auto-calculation). Whether teacher-determined or calculated, proficiency determination should aim for both accuracy and validity.

Translation of Competency Systems for Reporting

While traditional letter grades are typically not relevant in a competency-based system, a translation is sometimes needed to meet state, district or school requirements around grades, courses, etc. This can be challenging as competencies are binary, you either do or do not meet the expectations articulated in the competency progression. However, a few different methods are observed in schools. First, a competency-average is when the score on each competency (which was determined by an auto-calculation or teacher determination) is averaged across the competencies for the course. That resulting average is translated into a letter grade through a school-determined translation table. Second, competency-completion looks at the number of total competencies in a course and the number of competencies determined proficient and calculates a “percent-proficient” score. This score is then translated into a letter grade for the course. This last option avoids any averaging but does run into the issue of timing in that competencies are meant to be completed over time, so your percent-proficient score will increase over time.

Conclusion

Assessment of competencies tends to be the most challenging change for schools and districts implementing a competency-based system – especially when constrained by state reporting, eligibility, and college applications. Being clear on approaches and methods from the start can provide clarity for all members of the community.

Nate McClennen

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.