Strengthening K-3 Distance Learning

By: Jennifer Poon

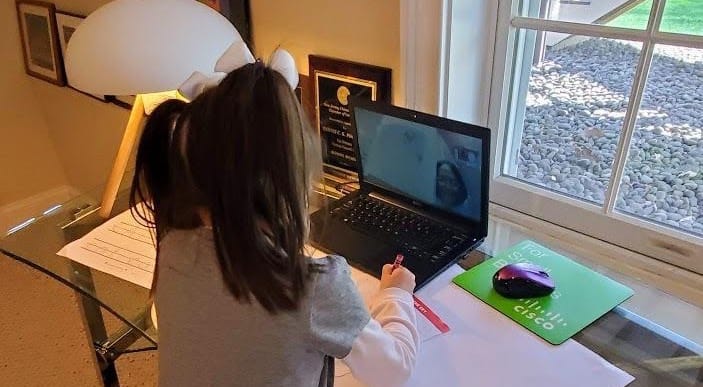

Pandemic school closures are problematic for the youngest learners who depend on live interaction and guidance for both social and cognitive development. To learn online, they need help to access platforms and videos, type, and log onto virtual meetings. Parents, caretakers, and older siblings have become important proxies for teachers during distance learning, but they are neither trained nor universally available to assist.

For these reasons many education leaders prioritize reopening K-3 this fall, but ongoing health and safety concerns may scare away significant numbers of students and teachers. Among those who return, symptoms of COVID-19 may force some students and staff back to distance learning. Without stronger options for K-3 distance learning next year, school systems will continue to lose young learners and widen achievement gaps. As pediatrician Dimitri Christakis said in an interview with Education Week, “Think about what that means for a 5-year-old or 6-year-old. Even a child from a well-to-do family is going to suffer detriments, but for low-income kids, the effects are going to be enormous and carry forward through the child’s entire life.”

I spoke with a handful of Kindergarten teachers in Indiana, Kentucky, and New Hampshire about their experiences with distance learning this past semester. Captured below, the challenges and ideas they shared are neither exhaustive nor easy but are offered as starting points for understanding what typically prevents young learners from engaging in distance learning, and building solutions that meet them where they are.

Some young learners are “missing in action.”

Some young learners are “missing in action.”

- Find and contact families, and partner with communities to meet basic needs. K-3 learners are particularly vulnerable to instabilities in housing and childcare during a pandemic. If a family is unresponsive to outreach, teacher Brandy Purdue advised keeping track of attempted communications and working closely with the school find someone who can contact them “through a different channel than the teacher has access to.” Once lines of communication are open, school staff can work with families and community partners to ensure every learner has the physical equipment, connectivity, and basic necessities to engage in productive learning.

Young learners need an adult to help them access and navigate their work.

- Make materials accessible. As Jennifer Manning describes, teachers can design resources so that early learners can approach them as independently as possible. Kandace Holder made instructional videos with clear and concise directions for how to complete activities. Dee Dee Jeffries offered multiple modalities for learning including computer-based, worksheet-based, and sent-home manipulatives. Purdue found that paper packets were more effective with parents who work from home because their child could work at a nearby table while parents used the computer.

- Engage families, too. Teachers stressed the importance of building trusting, empathetic relationships with families. Simply reassuring families that they’re not alone and offering flexibility based on their situation can create breakthroughs that increase engagement. Through direct communication, the teachers validated the family’s role in their child’s learning and provided concrete suggestions for what that role might entail (and, as Education Week reports, some offered a “crash course” in teaching key reading skills). Explicitness is important because families and teachers may have different perspectives on what learning looks like. As a parent, Purdue understands that families are inclined to help their child complete a task quickly so they can move on. But as a teacher, she appreciates productive struggle and encourages learners to succeed on their own.

- Be available and flexible. There is no sugarcoating it: to meet learners and families where they are, the teachers had to be responsive at all hours of the day. Holder scheduled Google Meets with her students throughout the day and evening to accommodate family schedules. If students didn’t or couldn’t sign up, she made phone calls and sent postcards. Many teachers responded to questions and provided feedback on student work late into the evening when the children of working parents were logged on.

- Prioritize assignments and focus on mastery. For families struggling to complete the work, Manning identified “must do” assignments like a subset of teaching videos and response sheets. Importantly, she and other teachers focused on evidence of learning, not completion of tasks. If a student demonstrates they’ve mastered a concept in ways other than the teacher’s assignment, it counts. This advice echoes the growing realization among educators that pandemic learning requires a competency-based approach to education.

Young learners struggle to focus on learning at a distance.

- Prioritize relationships, dialogue, and feedback. While it is difficult to keep “wiggly” students on task without being in the room, teachers found student engagement to increase the more they invested in live communication and dialogue. Regularly seeing faces (on videochat or even a prerecorded video) encourages young learners to keep focusing on school despite the change in format. Dialogue (live or asynchronous) allows teachers to continue building relationships with students and to better assess their strengths and struggles. It is also an important to providing feedback and encouraging socio-emotional wellness and development. As Manning notes, “The dialogue that can happen between a teacher and the student is what really can help our kids move to the next level.”

- Make learning personally relevant. As reDesign notes in their Tip Sheet for pandemic learning, teachers can activate student interest by selecting resources and designing assignments that spark curiosity, are relevant to students’ real lives, allow open-ended engagement, and provide authentic choices. Jeffries encouraged students to “bring your own” materials to lessons. Holder asked students to engage offline with the letter of the day and invited parents to share pictures of their interactions.

After a while, everyone gets tired.

- Build routines. Routines – such as a predictable schedule of a few meetings, a set of weekly assignments, and a rhythm of when and how dialogue and feedback occur – can support endurance by creating a regular cadence to the week.

- Create rituals and celebrations. When stamina fades as time wears on, rituals and celebrations can reinvigorate engagement and help young learners process inflection points in the curriculum or school year. Manning staged a “graduation ceremony” from her phonics unit, and Holder’s grade level team made virtual their annual “Reverse Alphabet” countdown to the end of the school year. Teachers can also use celebrations as motivational challenges for students, like how Holder promised a video of herself getting pie’d in the face if 80% of her class attended their Google Meets the last week of school. (It worked.)

Teachers can’t do it all.

While many of the ideas described here not new, all of them require more effort in a distance learning context; and some, like teaching parents how to teach, were never part of teachers’ original job descriptions. Teachers need system leaders, policymakers, and advocates to provide support for distance learning. For more on these critical roles, please see guidance such as this and this.

While success requires systemic solutions, teachers encouraged their peers to continue problem-solving, trying new things, and investing their finite energies where it matters the most. Were Manning to do things differently, she would have traded some time spent trying to plan the perfect lessons in favor of having more time for one-on-one or small group interaction with her students. Holder, too, quickly realized that it was worth the extra effort to provide as much “face time” as possible in order to tap into the relationships that are so central to learning. Teachers also found value in time spent collaborating with peers and supportive administrators, with whom they could trade notes and share the load.

For more, see:

- South Fayette School District: Leading Educators in Computational Thinking

- A Blueprint for Change Adits Pandemic

- Hardeep Gulati and Marcy Daniel on PowerSchool’s Unified Classroom Experience

Jennifer Poon is consulting as a Fellow at the Center for Innovation in Education.Her professional perspective has been shaped by teaching 9th graders about biology and coaching volleyball at King/Drew High School in Compton, CA, followed by her work at the Council of Chief State School Officer’s Innovation Lab Network where she helped federal, state, and local education leaders to nurture ground-up innovations leading to broader systemic change.

Acknowledgements

Sincerest gratitude to the following teachers who so generously shared their experiences with distance learning:

Kandace Holder, Kindergarten teacher at Newton Parrish Elementary School, Owensboro, KY

Dee Dee Jeffries, Kindergarten teacher at Heritage Elementary, Shelby County, KY, interviewed here.

Jennifer Manning, Kindergarten teacher at Memorial School, Newton, NH, interviewed here and here.

Brandy Purdue, Kindergarten teacher at Matchbook Learning, Indianapolis, IN

Lillian Snyder, Kindergarten teacher at Matchbook Learning, Indianapolis, IN

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.