The Case for Contribution: Why Schools Should Empower Difference Making

The great faith traditions built global communities of practical wisdom, of mutualism and purposeful service.

The Jewish tradition of Tikkun Olam involves acts of kindness to perfect or repair the world. It implies that each person has a hand in working toward the betterment of his or her own existence, as well as the lives of future generations—it asks people to take ownership of their world.

For Martin Luther, vocation is the locus of the Christian life. The purpose of every vocation is to love and serve your neighbors. God does not need your good works, Luther said, but your neighbor does.

Calvin, often credited (and blamed) for capitalism and the Protestant work ethic, preached service rooted in gratitude more than duty.

Social welfare is a principal value in the Islamic tradition. The practice of service to humanity is widely instructed and encouraged.

Dana, acts of generosity and giving, is the first theme in Buddhism. A kind and compassionate attitude toward every living being and the world is central to Buddist teaching.

The high holy days of Passover, Easter, and Ramadan all celebrate reconciliation—making all things new. The world’s great religions teach this spirit of reconciliation in daily life.

In response to a tragedy, the Rev. Dr. Gregory Groover, pastor of Boston’s Historic Charles Street A.M.E. Church, summarized this theology of reconciliation, “Each of us must figure out what we can do to create sustainable action as part of a greater overall mission to usher in true racial and economic justice.”

Contribution Outside Community

The new reality is that many young people do not grow up in communities of practiced religion—Generation Z is the least religious generation.

Instead, “Post-Millennials live in a culture of choice, self-actualization and freedom of expression,” said Sacred Heart Professor Christel J. Manning.

While positive for a sense of tolerance and leaning into the opportunities of the innovation age, this trend of non-religiosity raises questions. Will more young people grow up outside communities of caring adults? How will young people be exposed to role models of contribution?

Building Practical Wisdom

Contributing to the common good is a civic virtue. It’s one of four elements of practical wisdom identified by the Jubilee Centre for Character and Virtue at the University of Birmingham:

- Civic virtues: responsible citizenship and contributing to the common good;

- Intellectual virtues: the lifelong learning values of curiosity, critical thinking and agency;

- Moral virtues: the values of compassion and integrity that fuel ethical responses;

- Performance virtues: getting the work done with what others call growth mindset, grit and collaboration.

Developing these virtues—what some might call character education—has been a historical component of schooling, from ancient through modern times with the exception of a few decades at the end of the 20th century in many Western democracies.

After more than two decades of preoccupation with grade-level testing in reading and math (with little to show for it), a growing number of schools in the U.S. and around the world are returning to broader aims with contribution at the core.

In Loudoun County, near the nation’s capital, schools are “empowering all students to make meaningful contributions to the world.” Superintendent Eric Williams believes in “engaging students in solving authentic problems as a means to developing knowledgeable critical thinkers, communicators, collaborators, creators and contributors.”

Schools in the EL Education network share a character framework that says, “We help students get smart to do good.” At the center of the framework is “contribute to a better world.”

In the absence of a religious community or as a supplement for encouragement toward the common good, schools can support contribution with great benefit.

Why Promote Contribution?

Science and public opinion are building justification for schools to help young people come to understand the needs of the world, their strengths and interests, and where they come together for the common good.

Social science research points to a broader definition of success. In Dark Horse, Todd Rose concludes that a fulfilling life is not dependent on connections, money, or standardized test scores; rather, it is consistently making choices that complement personal interests and abilities.

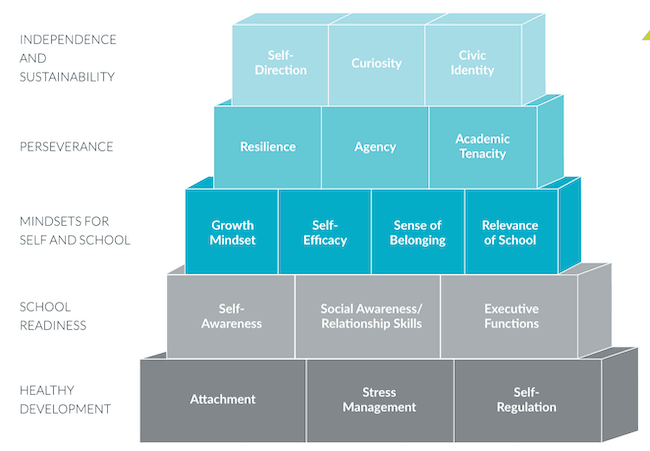

Finding a way to make a difference in the community uniquely develops all the top skills—self-direction, curiosity, and civic identity—identified by Turnaround for Children’s Building Blocks for Learning, a framework for the development of skills children need for success in school and beyond.

You don’t have to rely on social science to make contribution a priority; you can ask the school community what’s most important to them. Community conversations that yield broader aims, often called a portrait of a graduate, are always strong on what Jubilee calls the intellectual and performance virtues and typically includes the civic virtue of contributing to the common good.

Contribution is the innovation economy superpower. By taking on a complicated local problem and delivering value to a community, young people build agency and practice design thinking. It’s why Seth Godin frequently says that young people should learn to lead and solve interesting problems.

The benefits of contributing to the common good are embedded in wisdom traditions and should be central to education. Not only does it benefit the community, but it’s a shortcut to building the most important skills for life.

For more see:

- Empowering Students Through Choice, Voice and Action

- Contribution: Schools Alive with Possibility

- How to Be Employable Forever

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

This blog was originally published on Forbes.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.