Improving Autism Education with Community—And Robots

By: Dr. Lisa Raiford

Like other educational institutions in the country, we’ve seen rapid growth in the number of students with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) in South Carolina’s public schools. In South Carolina, in fact, we’re serving twice as many students with ASD as we were five years ago.

Of course, that influx puts quite a strain on the organizations and the teachers that serve them directly. As the Education Associate for autism with the South Carolina Department of Education (SCDE), it’s my responsibility to support them with evidence-based practices and ensure they have the tools to provide the education their students deserve.

Right now, 61% of our students with ASD are in general ed classes, which is pretty good, but we’d like to raise that number to 90%. It’s a challenging task, to be sure, but through a combination of professional development, collaboration and networking opportunities, shared resources, and assistive technology—including a charming robot designed to help students with autism develop social and emotional skills—we’re moving towards accomplishing that goal.

Building a Task Force

One of our initiatives is the Autism Spectrum Disorders Task Force. This group includes representatives from my own office, school special education administrators, other educators such as classroom teachers, ASD community agency directors, therapists, parents, and professors and researchers from universities and colleges.

The task force is charged with considering the needs of general and special educators with students on the spectrum, creating collaborative trainings for educators, parents, and other community members, and creating an ASD resource directory. The group also comes together as a think tank to look at what our students need in terms of programming and curriculum.

The resource directory the task force has created is a collection of materials for teachers, students, parents, and anyone else in the community who wants to understand autism better. Resources found there cover issues such as academics, social behavior regulation, transition, job opportunities, and other relevant research.

Connecting through an Annual Conference

To guide educators in putting those resources to use, we bring people together through free ASD conferences. We held the first one in November and it was a tremendous success. We’re very excited to hold the second one in the coming fall.

The conference is planned by the task force as well, and we try to involve community agencies as much as possible so that the conference becomes an easy way to tie parents and students and teachers into resources. There’s no need to reinvent the wheel—these groups already offer a lot of helpful services, but a lot of times families just don’t know what’s available to them.

As part of the first conference, we held sessions for parents where they were provided with specific information about their children’s education so that they could in turn discuss with educators what they need and what their hopes are for their children.

Creating Momentum with New Tools

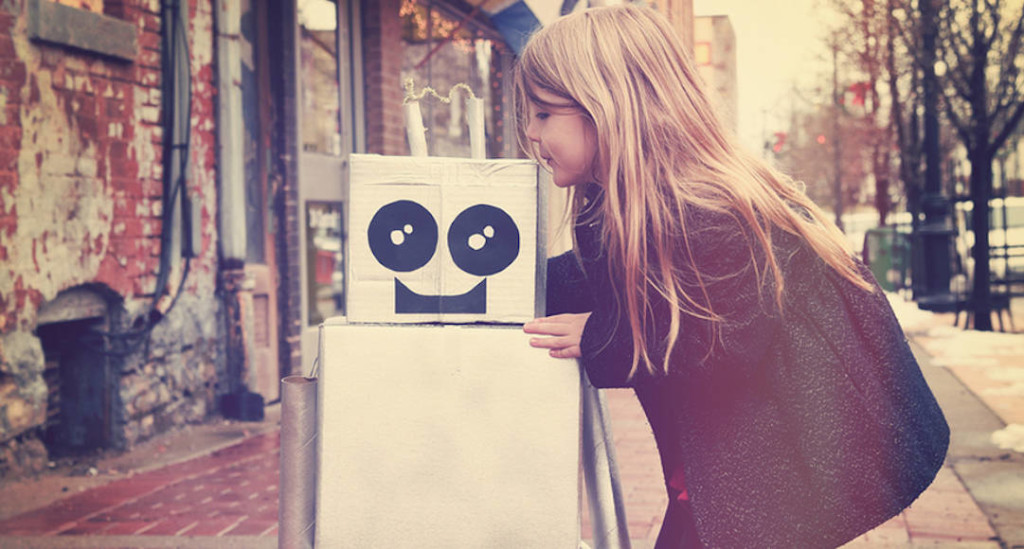

Another initiative that we’ve seen tremendous success with is a three-year pilot program with Robokind. Through their Robots4Autism program, they offer two-foot-tall robots, named Milo and Robyn, that are paired with a social-emotional curriculum. We’re in the second year of the program right now, but we’ve already studied the results of the first year, and they are more than we hoped for.

The specific goals of the pilot were to help our students with ASD improve their social and emotional understanding, communication and self-regulation, and the ability to generalize those behaviors with their families and peers.

We began the pilot with 16 schools around the state and 21 robots. For support, a few team members and I visit the participating schools for onsite visits. There’s also frequent email communication between participants and my office to address any challenges, and we have meetings during the summer with participants to brainstorm, explore challenges and successes, and plan next steps for the following year of the pilot.

In the first year, students completed 13,769 lessons, and 90% of them demonstrated mastery resulting in observable transference of social skills to human-to-human interaction. Of those who demonstrated mastery, 70% did so after repeating lessons: Milo and Robyn never get bored or tired or frustrated with students, no matter how often they need to repeat something.

That 90% number was very exciting for us. It measured the mastery of skills included in the curriculum to see how many students are getting the answers right, and any students missing more than one question are not included in that number. Anecdotally, we’re seeing those skills translate into the natural environment with their teachers and peers and families—those students are generalizing the skills they’re learning, which was our overall goal.

The results also demonstrate that the repetition students are able to engage in helps them learn to take those skills from a one-on-one setting—because of course this program would be nothing without our teachers in place—and use them in wider, natural settings. We’ve seen our students who have learned some behavior regulation skills, such as being able to calm themselves down and use common language when they’re frustrated in a regular classroom to get to a calmer place, rather than leaving the classroom.

After the first year’s success, we allowed several districts not selected for the pilot to adopt the program and now have more than 50 districts across the state participating. It’s been very successful not only in the implementation but in its longevity. Teachers are excited about it, and the results that we’re seeing in our students and hearing from our teachers and families has been amazing. The best feedback comes straight from educators when they call and tell us, “This kid made a breakthrough,” “This child focused their eyes on me for the first time,” or “This child said a word to me that they’ve never said before.”

Our families are calling us and saying that, for the first time, their children are interacting and they can take them places they’d never been able to take them before. We’re proud that we can help to provide these students with the skills they need to thrive in school and the wider world.

For more, see:

- A 21st Century Model of Special Education

- South Carolina’s Statewide Movement to Personalize Learning

- A Blended Environment: The Future of AI and Education

Dr. Lisa Raiford is the education associate for autism at the South Carolina Department of Education. She can be reached at [email protected].

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.