One Year After Helene: WNC Schools Anchor Recovery in Resilience

By Wes Davis

One year after Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina, the visible scars of the storm remain. Families are still displaced. Some school buildings sit empty. But across the mountains, educators and communities are working on something less visible and far more lasting: weaving resilience into the future of learning.

The WNC Resilience Project, launched in the wake of Helene, is helping districts recover while reimagining what schools can be. To date, 18 school districts have joined efforts, and nine districts are deeply engaging. Its premise is simple but profound: rebuilding after a disaster should not only restore what was lost but create something stronger, more connected, and more responsive to young people’s needs.

Rebuilding with Community at the Center

At Canton Middle School in Haywood County, administrator Joshua Simmons describes the shift. The crisis revealed how indispensable schools are, not only as places of learning but as anchors of community. That lesson now guides how his school approaches recovery.

“It becomes more than just a learning institution,” Simmons said. “It becomes like your home. And people needed it when they got back.”

Today, Canton Middle sustains that sense of belonging through weekly all-campus assemblies. A tradition born out of the storm, and a renewed commitment to empathy-driven leadership, everyone, including leadership, young people, and support staff, join and take on specific efforts as a collective each week to contribute to a positive experience at the school. Staff have become more attuned to the challenges learners carry into school each day, adjusting expectations and supports accordingly.

Turning Pain Into Purpose

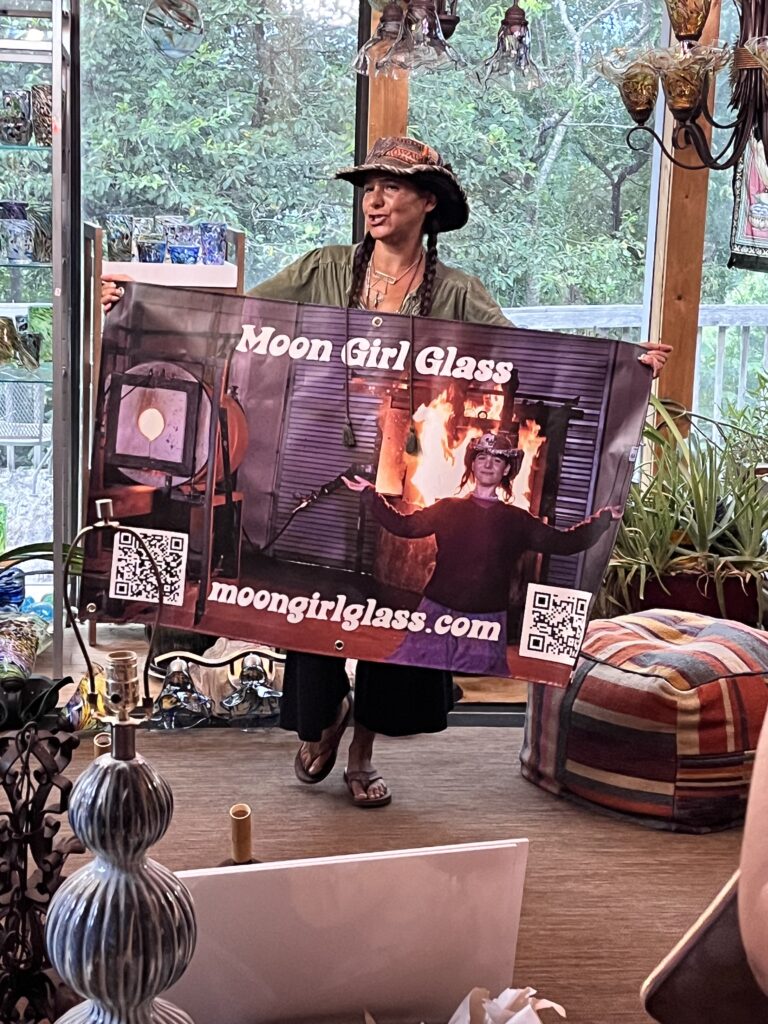

In Madison County, the work of recovery has also taken creative forms. Madison County Early College High School English teacher Julie Young and local glass artist Kristen Muñoz launched Stories in Glass, a project that invited learners to transform shards of broken glass into art, including bees, butterflies, and other symbols of renewal.

“I wanted to teach them that we could turn pain into purpose together through creating and transforming,” Muñoz explained, describing how she drew on the Hawaiian prayer Ho’oponopono to guide the process.

Julie, a 36-year veteran teacher, saw how the project gave her students agency at a time when so much felt out of their control. Instead of writing a traditional research paper, they designed an interactive website to collect community storm stories, gaining skills in interviewing, podcasting, and design along the way.

“This is my passion,” she said. “If it wasn’t for challenge-based, community-based learning and partnerships like with Kristen, I don’t know… it wouldn’t be the same.”

For both Julie and Muñoz, the project wasn’t just about art. It was about rebuilding faith in community. “The most important thing,” Muñoz said, “is for us to be getting together and rebuilding our faith and our trust in life and in each other. And who better to tell that and share that than the kids? Because as you know, they have the biggest hearts.”

The Strands of Resilience

Across Western North Carolina, the Resilience Project is giving schools both structure and freedom to respond in ways that fit their own contexts. Six strands guide the work—from mental health supports and recovery-related learning to new credentialing pathways, community partnerships, and systemic leadership. They are not abstract frameworks but entry points for educators and partners to ask: What matters most here, and how can we build it into daily practice?

Each district meets regularly to test ideas, learn from one another, and adapt. In some places that means a single classroom piloting a new practice; in others, whole schools or districts are engaged. What ties the work together is a simple improvement cycle (plan, do, study, act) that makes resilience a daily practice rather than an aspiration.

Already, the work within the strands is visible. Hendersonville Middle in Henderson County is using GLAD (Guided Language Acquisition Design) strategies to stretch higher-order thinking. Valle Crucis in Watauga County is building belonging through interest-driven lessons and intentional, personalized morning greetings for each learner, while Buncombe County schools are using movement and dialogue to strengthen connection. In Haywood County, educators are working with statewide ecosystem SparkNC to prototype a credentialing system that embeds resilience and grows student agency, with links to CTE, mentoring, and internships.

Across districts, empathy mapping is grounding the work: teams consider a composite learner on the margins and design supports that, while targeted, benefit all young people. The throughline is clear. Academic growth remains central, but educators see that readiness to learn—having resources, emotional support, and meaningful work that spark engagement—is the necessary condition for success.

This fall, cycles of reflection and action are underway. Teachers are using microgrants with Western Carolina University to design lessons marking Hurricane Helene’s one-year anniversary, turning memory into meaning. District teams are building prototypes identified over the summer, with milestones set for November. Gatherings—from an October field trip on the French Broad River to a late-November convening—create space to notice what’s working and carry lessons forward.

A Culture of Resilience

For Simmons, resilience is not an abstract concept. He still drives bus routes where families live in campers and where flood debris remains piled on riverbanks. Yet in classrooms, he sees learners leading projects, collaborating, and showing up for one another in ways that reflect both the hardship they’ve endured and the strengths they’ve discovered.

“Kids are the most resilient people in the world,” he said. “They’re just back ready to learn.”

That spirit is shaping schools’ approach to academics and beyond. Districts are aligning recovery with North Carolina’s Portrait of a Graduate, which calls for learners to develop skills like adaptability, empathy, and collaboration. In practice, that has meant integrating problem-solving into lessons, giving students more voice in shaping projects, and supporting educators to design with care and flexibility.

Lessons Beyond the Mountains

The WNC Resilience Project is still in its early stages. But its approach, which is rooted in community values, designed by educators themselves, and supported through regional collaboration, offers a model for other places navigating crises.

This isn’t about importing programs or quick fixes. It’s about investing in people, relationships, and structures that make schools more adaptable over time.

For communities far beyond the Blue Ridge, the lesson is clear: resilience is built day by day, in relationships and in classrooms. And when schools become homes in the truest sense — places where young people and adults feel seen, safe, and supported — recovery can be the spark for something enduring.

Wes Davis is the Leader of the Western North Carolina Resilience Project and the Outreach and Program Director for Open Way Learning, a nonprofit committed to amplifying the joy and wonder of learning through co-design and learner-centered innovation. With a background in life science research and over twenty years in student-centered education, Wesley has helped students publish children’s books, conduct photo surveys to design zero-waste campuses, explore place through learner-designed field trips, and dream up woodworking projects that strengthen community connections. Wesley lives in Western North Carolina, where he partners with school communities to build cultures that support transformative change.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.