What Educators and Families Should Prioritize in the Age of AI

Key Points

-

Being a learner for life is not about filling a pail but lighting a fire.

-

Instead of practicing tasks that AI will increasingly perform, educators should shift our focus to enhancing uniquely human capabilities—amplifying learner potential through a focus on agency and intellective competence.

At first, it’s disconcerting. As well-crafted sentences appear on the screen, we can almost hear the keys clacking. But no one is typing; the words simply appear. And the pace is furious. No human could write this fast.

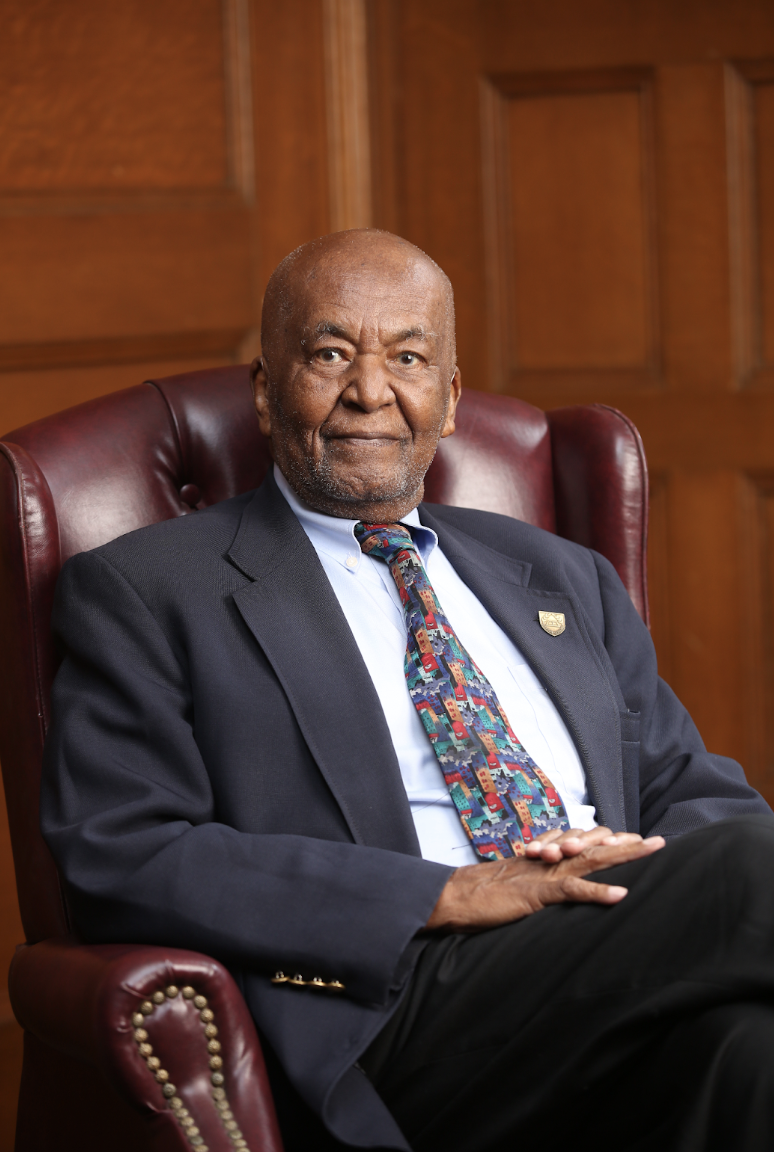

For the two of us—educators born almost 60 years apart—it’s a marvel to see what generative artificial intelligence (AI) can do. One of us, Professor Edmund W. Gordon, was born in 1921 and has served many roles throughout an 80-plus-year career: from psychologist and minister to civil rights leader and public servant. The other, Eric Tucker, born in 1980, is a parent of school-age children, a special educator, a former superintendent, and a technologist. Despite our different perspectives, this new reality of AI leaves us pondering: If AI can produce something that takes the typical student years, even decades, to master, what does it mean to be educated?

As the launch of ChatGPT marks its first anniversary, we’re not the only ones asking these questions. Tumult at OpenAI, the non-profit AI research and deployment shop and publisher of ChatGPT whose mission is “to ensure that artificial general intelligence—AI systems that are generally smarter than humans—benefits all of humanity” creates something of an Overton window to consider what broadly distributed benefits for AI might look like in the field of education.

A Biden administration executive order and report highlights how educators and schools might navigate the rapid expansion of AI, arguably one of the most significant transformations since the War on Poverty, of which Dr. Gordon was a key architect during the Johnson administration.

Dr. Gordon’s scholarship has considered what it means to be human and how technologies amplify learning and development over a career that included contributions to numerous presidential administrations, including Kennedy’s desegregation efforts, Johnson’s creation of Head Start, and Obama’s Promise Neighborhoods. To paraphrase Gordon: Being a learner for life is not about filling a pail but lighting a fire.

In the wake of the public debut of ChatGPT, Claude, and Bard, it’s clear that AI’s influence is here to stay. So while it’s worth understanding the risks—including the potential for AI to disrupt human jobs, metastasize bias, reproduce mistakes, undermine privacy, and cause unintended consequences—it’s also important to understand AI’s possibilities for enhancing human potential and informing educational processes.

As educators, we’re interested in how these technologies could help students learn in a manner that honors learner variability. How can educators and caregivers orient our work regarding these tools to ensure all children thrive in an uncertain future? While the technology is different, educators have considered these types of questions before. We’ve gone from encyclopedia sets to Google workspaces, from one-room schoolhouses to Zoom seminars. As the storm of AI-fueled transformation makes landfall, we believe educators should understand the emergence of AI as an opportunity to take stock of what matters most for learners in the period ahead.

What It Means to Educated for the Future

In the face of emerging technological advances, Carl Bereiter and Marlene Scardamalia (2013) considered human competencies that matter in an uncertain world. They elevate the ability to create knowledge, find real-world applications for abstract ideas, understand and operate within complex systems, sustain focus amid multiplying distractions, and engage in collective work.

Similarly, the XQ Institute has identified research-backed goals, or learner outcomes, that students must develop to be successful in the future. These include agility in their ways of thinking and making sense of the world, building collaborative capacities such as self-awareness and social awareness, and cultivating curiosity to become lifelong learners.

Studies show too many U.S. high school graduates need remedial courses in college and don’t master the skills employers increasingly prioritize. XQ is working to change that by redesigning the high school experience. XQ’s Learner Outcomes help educators identify how to engage students deeply in their learning to master the knowledge and skills necessary to meet the challenges—and opportunities—they’ll need for college, career, and any other future success. Within these outcomes are numerous competencies aimed at developing skills such as critical thinking, social awareness, and self-management.

For example, when Eric Tucker co-founded the Edmund W. Gordon Brooklyn Laboratory High School in 2017, the curriculum emphasized the practice and presentation of applied research. For each year of high school, students completed interdisciplinary year-long seminar courses sponsored by the College Board, investigating pressing issues of social concern in various disciplinary contexts, writing research-based essays, and designing and giving presentations as teams and individuals. Students completed research projects on topics they chose—from environmental justice to gun control, affirmative action, and economic mobility—gathering and combining information from various sources, viewing an issue from multiple perspectives, and crafting arguments based on evidence.

Such competencies are human competencies—abilities that, at present, technology cannot fully replicate. In the face of AI, we, as educators, are the ones who must help all learners cultivate these competencies. We must shift education to focus on human potential, to develop students’ breadth and depth of knowledge, as well as their ability to navigate diverse ideas, people, and cultures. This is not a job a robot or algorithm can perform.

Focusing Education on Human Potential

Instead of practicing tasks that AI will increasingly perform (such as producing a first draft of an essay outline, generating initial lines of code, or preparing a range of preliminary visualizations of a statistical analysis), educators should shift our focus to enhancing uniquely human capabilities—amplifying human potential through technological advancements and beyond. Schools should embrace generative AI and similar tools to increase time spent honing competencies such as framing meaningful questions, contextualizing arguments, and evaluating multiple perspectives.

Dr. Gordon’s scholarly work explores two competencies that are particularly important for educators to focus on:

Human agency. Agency is the ability to recognize and act in the best interest of yourself and others. Another way to think about it is the ability to hold onto a sense of efficacy and enact your values. Ana Mari Cauce and Gordon (2013) define human agency as the propensity to take action and to be goal-driven.

Human agency is significant because it enables people to act for the collective good. As Viktor Frankl, the Holocaust survivor and psychologist, captures so beautifully in “Man’s Search for Meaning” (1954), fulfillment ensues “… as the unintended side-effect of one’s personal dedication to a course greater than oneself.” In an era of AI, we can amplify agency by using tools that enhance the ability to act meaningfully in the surrounding world.

This is particularly true when confronted by complex existential threats like climate change. Educators focusing on student agency can work with students on how to use AI to address environmental challenges. Students might explore how AI can support campaigns to lower energy consumption and greenhouse gas emissions, monitor deforestation, or track carbon removal. The International Society for Technology in Education’s guide, for example, proposes students research and identify a local environmental or sustainability challenge, define the problem in detail, explore how an AI-powered solution might fit into the more extensive solution, and create and test a working prototype. In this example, an agentic learner can practice setting authentic goals and using AI to help solve a real-world problem.

Intellective competence and character. Dr. Gordon coined “intellective competence” (2013) to describe the ability to use knowledge, technique, and values to engage and solve novel problems. He uses the term “intellective character” to reflect that what we want learners to know and be able to do must be instrumental to achieving what we want learners to be and become. Intellectual character implies becoming a good citizen and creatively using imagination to address challenges and improve circumstances.

The ability to make sense of and address such problems sets humans apart from our ever-evolving technological counterparts. For example, Chris Terrill from Crosstown High highlights schools worldwide where students work together to address environmental challenges, big and small. Educators can strengthen intellective competence by engaging students using AI tools for sustainability challenges. Platforms such as Wildlife.ai, Restor, and Zooniverse suggest how AI might help provide insights into environmental challenges such as climate change, protecting ocean ecosystems and wildlife, water and plant conservation, or air quality. Intellective character orients a learner’s urgency, values, and commitments toward environmental justice.

Educators and students in classrooms around the country are exploring future-leaning approaches that resonate with Gordon’s notions of agency and intellective competence. Notably, XQ schools such as Latitude High School in Oakland, Iowa BIG in Cedar Rapids, and the Purdue Polytechnic High Schools in Indiana demonstrate how meaningful projects in which students have a voice in their learning and collaborate with community partners can nurture these competencies.

As technological breakthroughs, analytic methods, and artificial intelligence (AI) rapidly redefine what it means to be educated, they correspondingly transform how we can measure and inform learning and development. At the Gordon Commission Study Group, we believe that now is the time to accelerate measurement and assessment system innovation to maximize learning and thriving for every learner. We are working to study the best of assessment, data, and AI practice, technology, and policy; consider future design needs and opportunities for educational systems; and generate recommendations to better meet the needs of students, families, educators, and society.

The emergence of generative AI signals a sea change for what it means to be educated. Our challenge to fellow educators is to join us in rethinking what it means to learn and thrive, given AI-powered tools. Our combined 100-plus years of experience as parents, educators, and applied researchers lends us confidence. We can embrace agency, encourage intellective character, and foster the abilities that shape us as individuals and help us create a healthy, just, and sustainable world.

Eric Tucker

Michael Maser

I value your posting; it poignantly hones a focus on human competency as distinguished from machine / artificial intelligence.

I recently completed my PhD on the subjectivity of learning (Simon Fraser University, Canada), confirming its primacy in a taxonomic standoff with objectivist learning - a kissing cousin of AI. How we-educators can best support the dispositions and sensibilities you identify is through personalized/personalizing learning. This is of rising implementation across many educational jurisdictions, especially in the US, but it still needs a lot of practical help, including support for educators seeking to implement it, beyond lip service. My dissertation can be located here: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/36598 Cheers, Michael Maser