How Systems And States Can Encourage More And Better Project-Based Learning

Project-based learning is on the rise–at least it was pre-pandemic. The sudden shift to online learning appears to have brought with it more worksheets (just digital this time) and bite-sized tasks–and with it less engagement, less integration, and less application.

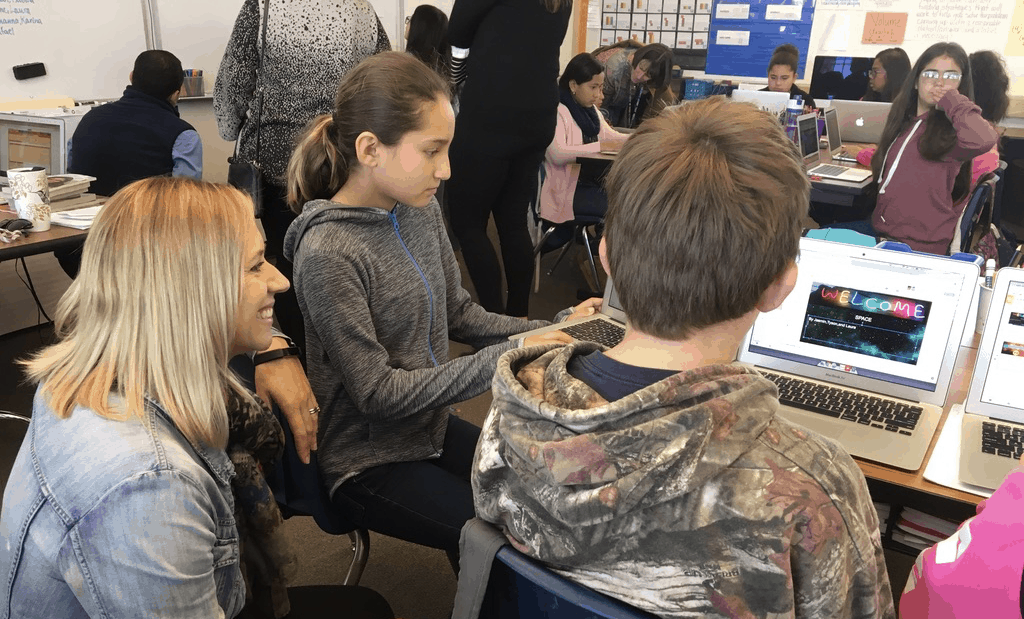

The long-term trend toward more project-based learning makes sense because it engages students in authentic learning, it develops critical skills including problem-solving, communications, collaboration, and project management–and it often applies those skills in new contexts that build transferability.

Perhaps most importantly, if you want young people to develop agency–confidence in their ability to act on the world–and be ready to deal with complexity and unpredictability, they have to engage in extended challenges. And ideally, learners would have the opportunity to find, frame, initiate and manage some of their own deep dives

However, it’s hard to develop and support good projects. This winter weather reminds me of a visit to a northern elementary school that claimed to be “project-based” but their big fall project was paper snowflakes. Yes, the kids were engaged and there was a public product, but it was a low-level activity, not a project packed with important knowledge and skill-building.

Valuable projects take time to plan and to execute. They often cut across traditional disciplines and may require faculty collaboration. And, it can be difficult to get all students prepared to contribute to demanding challenges.

Leading experts supported the development of the High-Quality Project-Based Learning (HQPBL) framework with support from PMIEF. It provides guidance to teachers on what high-quality PBL student experiences ought to look like and include. States and school systems can adopt frameworks like HQPBL.

A policymakers guide from XQ offers useful advice for advancing next-generation learning: empower local communities, make diplomas meaningful, and get teachers the tools they need. Tips relevant to project-based learning are discussed below.

Empower local communities

XQ, NewSchools, and Walton’s Innovative Schools Program are great national nonprofit examples of supporting innovative new schools.

The best example of a public-private school development partnership state was the Texas High School Project launched in 2003 resulting in 135 quality STEM and early college high schools. Strong results were promoted by solid grantmaking and technical assistance from a dedicated organization (now Educate Texas). The state-defined early college high schools and defined how funds and credits flowed.

The best example of a PBL-focused city school development partnership is El Paso ISD and New Tech Network where 10 new schools that exemplify high-quality project-based learning kick-started a district-wide Active Learning strategy that combines personalized and project-based learning.

States partners can provide instructional guidance like the Texas Learning Exchange School Instructional Supports Guide.

Systems can promote powerful project-based learning by collecting high-quality examples of public products like Models of Excellence from EL Education,

Make diplomas meaningful

Advocating for broader aims like the Profile of a Virginia Graduate is a useful example of steps states can take to encourage project-based learning. State Superintendent Dr. James Lane created the Virginia is for Learners initiative, a collaborative of 60 school districts to promote deeper learning in and out of school and to measure what matters.

Like Vermont, states can create proficiency-based graduation requirements that encourage interdisciplinary projects and demonstrations of mastery through portfolios.

States can support sharing of extended transcripts. Texas supported the adoption of Greenlight Credentials which enables portions of a comprehensive record to be shared with colleges and employers. State universities could be encouraged to consider project portfolios and demonstrated competencies as evidence beyond test scores for admission.

States could encourage a capstone project. A few examples of California schools with great capstone project traditions include engineering projects at Design Tech High School, a senior legacy experience at Minarets High School, and iLEAD Schools where a culminating capstone concludes in a Showcase Of Learning.

States and systems could also sponsor science fairs and encourage participation at least twice in secondary education. The Society for Science is providing Emergency Fund Grants to their affiliated fair network, as they work to host their fairs during the pandemic, this has occurred in Maine, Southeastern Ohio, and Southern Appalachia and could be done at scale during non-emergency times.

Big project-based networks like New Tech Network and Harmony Public Schools share project authoring, management, and assessment tools and strategies. Teachers in the 200 New Tech schools are able to adopt, adapt, or author projects utilizing a project-based learning platform.

Good project-based learning is difficult to promote through legislation but barriers can be reduced and enabling conditions can be created.

After a year of small problems, digital worksheets, and Zoom classes, it’s time for some real projects–work that matters to learners and their community. Rather than doubling down on drill aiming at “learning loss”, states and school systems can support learning that inspires, engages, and empowers learners with projects that students will remember 20 years from now.

For more, see:

- A Key Component of Student Voice

- It’s Time to Plan Summer Learning Opportunities

- 20 Invention Opportunities in Learning & Development

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.