From On Edge To On Track: Elements of Trauma Sensitive Schools

By Dustin Bindreiff

Finding a way to help a class of students develop resilience and support each other, while meeting the myriad of pacing calendars and school activities that fill up a school day is a tall order for even the most skilled teachers. Fortunately, the research base around trauma and resilience has advanced and an easier-said-than-done framework for creating trauma sensitive schools is emerging. In particular, research consistently highlights three common components to resilience:

- Belonging: Developing supportive relationships with others, especially caring adults.

- Agency: a sense self-efficacy and control over one’s life,

- Meaning: A greater understanding of life, spiritual or religious connection and sense of purpose.

Belonging and Trauma: Am I Safe?

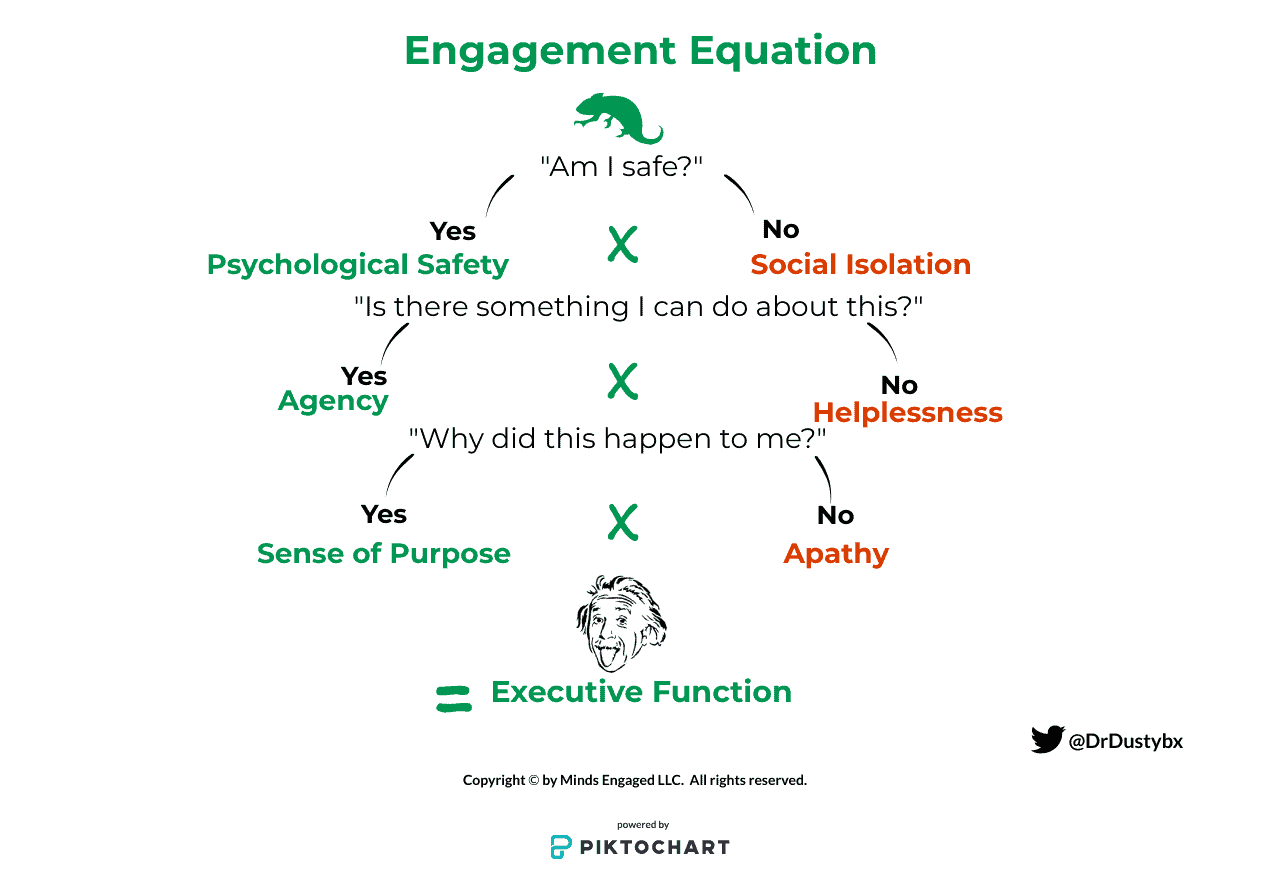

Victims of trauma will often arrive at school with their brains focused on survival and detecting threats in the environment. As a result, they may struggle to focus on learning to cross multiply fractions, ask thoughtful questions, be creative, wait, or manage frustrations. Additionally, students in this mindset will be highly sensitive to the slightest social slight, potentially leading them to greatly overreact to benign interactions.

The process of shifting students from a focus on self-protection to engaged curiosity begins with providing students a sense of belonging. Belonging, the sense of physical and psychological safety is the first step to accessing executive functioning skills. A sense of safety puts the amygdala, the brain’s threat radar center, at ease allowing attention to focus on learning. This helps explain why the most frequently emphasized aspect of addressing trauma is the development of supportive relationships; in the case of children, especially with adults. As the Harvard Center for the Developing Child explains “The active ingredients in building resilience are supportive relationships with parents, coaches, teachers, caregivers, and other adults in the community.”

The classroom is a highly social place; everything students do is observed and judged by peers and adults. For even the most well-adjusted students, this can make raising a hand to say “I don’t understand.” an act of courage. This pressure becomes compounded for trauma victims and even more so when they also have learning difficulties. Their hypervigilance in such highly public settings can compound sensitivity to environmental cues and results in high levels of stress hormones coursing through their body making self-control nearly impossible.

Agency and Trauma: Is There Something I Can Do About It?

Children are not born with resilience, it is a learned response to an adverse experience. George Bonanno heads the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Lab at Columbia University, and has been studying resilience for nearly 25 years. Bonanno has come to conclude that a central element of resilience is perception: Does the child perceive an event as traumatic, or as an opportunity to learn and grow? In order to help young people develop post-traumatic resilience, we will need to empower and challenge students so they can rediscover the control they have and overcome the victimization they experienced.

Martin Seligman spent much of his career studying how exceptional humans overcome adversity. His work helped soldiers and trauma victims regain this sense of agency by shifting their attribution of the traumatic events in key ways. His work focused on helping trauma victims shift how they interpreted events from internal and permanent factors to external and temporary. These shifts returned a sense of agency to many trauma victims, allowing them to regain a sense of control; leading the way to post-traumatic growth rather than stress.

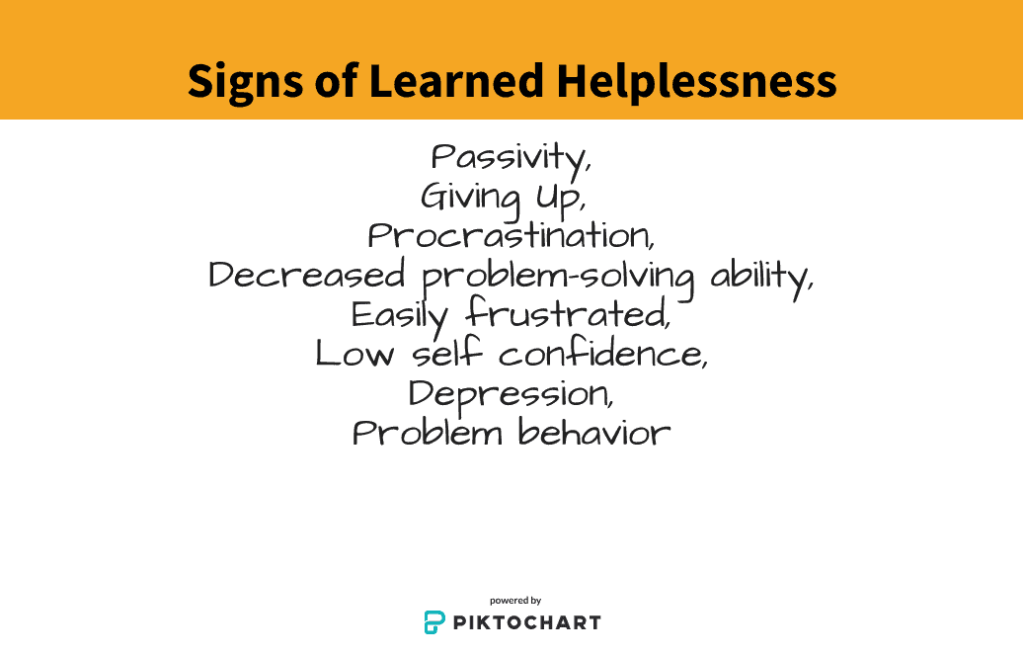

The popular growth mindset research of Carol Dweck and others is another avenue to promote agency in students. When students are able to maintain a growth mindset they are able to stay focused on the actions they can take to learn, heal and transcend. However, if they come to believe their circumstances are fixed or that they are abused due to their character they will become at increased risk of learned helplessness. When this happens, traumatized students may shift their attention from learning to turning the classroom into a playground to distract them from the pain stored in their body.

Meaning and Trauma: Why Did This Happen to Me?

One of the primary functions of the brain is to find patterns, whenever we encounter a new experience our brain is driven to answer “Why did this happen?”. In many ways, finding this connection between cause and effect is what learning is. This is especially true when we experience traumatic events. In order to survive, our brains have become especially sensitive to pain and finding ways to avoid it.

This is why helping students find meaning in their traumatic experiences is especially critical. Trauma creates a crisis of meaning, destroying our sense of order and trust in the world. Traumatic events can be especially challenging because they are overwhelmingly painful experiences with little or no connection to a child’s behavior. Additionally, many victims of abuse or neglect are growing up unable to do anything to make the pain stop. This senseless suffering can further challenge our most basic beliefs about the world; undermining assumptions about the meaning or basic goodness of life and people.

Helping students find meaning in their life and experiences an important element of creating trauma-sensitive schools. Finding meaning can reduce feelings of vulnerability and help restore fundamental assumptions that the world is benevolent, predictable, and meaningful. Victor Frankl’s groundbreaking work during his time in Nazi concentration camps detailed the fundamental drive to make meaning of suffering and the critical role it plays in survival and post-traumatic growth. Learning and success require a great deal of personal effort and resilience for even the most talented students.

Why would a student put in this effort and risk further failure if they feel their life and actions have no purpose? Finding meaning or purpose from the traumatic events can shift students from victimization to the personal power that inspires and transcends the most difficult experiences.

Brains Are Wired to Survive in Their Environment

The critical element of trauma is the emotional response, this is what triggers the fight-or-flight response. These emotions are stored in the body as much as in the brain. As a result, the behaviors of traumatized students can defy logic; they are emotional, not logical. They are often responding to subtle environmental triggers that activate emotional responses stored in the body, long before these cues are processed by the executive functioning areas of the brain.

Prior to working in education, together I spent a decade working in the nonprofit sector as a mentor. This experience allowed us to witness the impact that trauma, racism and intergenerational poverty have on children. Experiencing the vastly different environment many children grow up illustrated the fact that for many children their brains have been wired to survive in violent communities with few supports or resources. Sitting calmly and learning the quadratic equation requires fundamentally different neural pathways than those needed to survive when traumatized students go home.

In order to better support students growing up in adverse circumstances, it is important to develop an understanding of the impact of trauma on brain function. These experiences can shift neural pathways away from executive functioning and toward the more primitive fight-or-flight response. As Figure 2 highlights, when we can create learning communities that radiate belonging, agency and meaning we provide an environment for trauma victims to heal and grow. While this will not solve or remove a child’s pain it will provide them the support, confidence and purpose to help them heal themselves.

For more, see:

- Trauma-Supported Education and Educator SEL Training is Vital for The Classroom

- Addressing the Hidden Effects of Trauma in a School Community

Dustin Bindreiff has 20 years of experience as an educator and mentor and is a TA at the State Performance Plan Technical Assistance Project.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.