Developing Skills for School, Work and Life Requires a Systematic Approach

Over the last 20 years, I and my fellow reformers have settled on a grounding exercise that has proven effective in establishing shared values for educational outcomes.

When I was at the Buck Institute for Education (now PBLWorks) we developed a workshop activity called the Ideal Graduate. Colleagues such as Ken Kay, founder of both EdLeader21 and the Partnership for 21st Century Learning, and Bernie Trilling, the former global director of the Oracle Education Foundation, employed similar activities. We challenged audience members to create a list of the skills, attributes, and knowledge learners needed to be successful in college, career, and community.

In every country in every context the list of skills, attributes, and knowledge are essentially the same: Our Ideal Graduate is an effective collaborator and communicator who uses creativity and critical thinking to solve problems and generate solutions that are meaningful to themselves and effective for their community.

Thought leaders in this space came to a tacit agreement with audiences, funders, researchers, policymakers, and community members. We agreed on the following:

- These skills can and should be taught to all learners.

- All learners deserve equitable opportunity to develop these skills.

- These skills should be assessed on a regular and systematic basis.

- These skills are most likely to be enhanced by inquiry-based pedagogies such as Project-Based Learning (PBL).

That’s a glorious list of assumptions, but as always I like to examine assumptions, especially my own. The assumption I currently struggle with involves our understanding of how skills are actually developed. Per my background in PBL, I wrote a Driving Question: Is how we are teaching and encouraging skills actually the way learners develop them?

One of the default assumptions in education is that learners develop skills (and knowledge) the way a toddler learns to climb stairs, i.e., one step at a time. Robert Siegler, a professor of cognitive psychology at Carnegie Mellon University, dismisses the staircase analogy and argues for another in his book Emerging Minds:

“Rather than development being seen as stepping up from Level 1 to Level 2 to Level 3, it is envisioned as a gradual ebbing and flowing of the frequencies of alternative ways of thinking, with new approaches being added and old ones being eliminated as well. To capture this perspective in a visual metaphor, think of a series of overlapping waves, with each wave corresponding to a different rule, strategy, theory, or way of thinking.”

Siegler is not the first researcher to ponder the process of skill development, a line of inquiry that stretches back to the late 1890s. One of the most notable frameworks is called the Dreyfus model of skill acquisition, which was developed by brothers Stuart and Hubert Dreyfus at the University of California in 1980. Their model suggests that learners pass through five stages of skill development:

- Novice

- Competence

- Proficiency

- Expertise

- Mastery

Six years later they released a book called Mind over Machine in which they made a few changes to the sequence: Novice, Advanced Beginner, Competence, Proficient, Expert. That revision is cast in shadow due to the brothers’ early exploration of A.I. and its significance.

Researchers beyond the field of cognitive psychology who focus on skill development in sports or careers have also generated theories that can inform our current discussion.

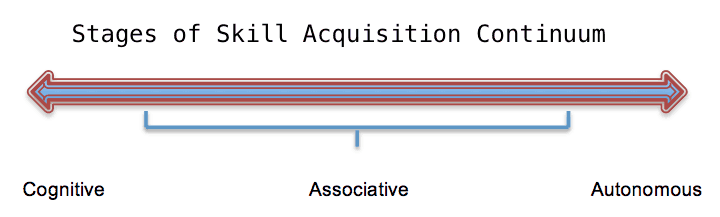

Paul Fitts and Michael Posner developed a 3-Phase Model in 1967 framed around the following stages of motor-skill development:

- Cognitive phase: Learner breaks down the skill into smaller elements and learns how to combine these elements to perform the task.

- Associative phase: Learner begins to understand what works and what doesn’t, enabling them to enhance effective techniques and drop the ineffective.

- Autonomous/Procedural phase: Learner perfects the target skill while learning to ignore inputs that are irrelevant via automaticity.

Image Credit: Daniel Patrick (https://www.pdhpe.net/factors-affecting-performance/how-does-the-acquisition-of-skill-affect-performance/stages-of-skill-acquisition/)

Dee Tadlock and Rhonda Stone described a Predictive Cycle Model in 2005 that includes four stages. It diverges significantly from the Fitts and Posner model in that the learner does not have to consciously understand the components of a skill. The stages are:

- Attempt

- Fail

- Implicitly analyze the result

- Implicitly decide how to change the next attempt so that success is achieved

This discussion should make apparent that a simplistic view of skill development is detrimental to our shared desire for students to develop skills that will serve them well throughout their lives. We should also understand that skill development is an ongoing process that has stages that may entail backsliding per Siegler’s framework. That understanding significantly impacts how we assess these skills and provide meaningful and actionable feedback to learners.

What is a teacher to do? Educators often loudly complain when writers like me broach the topic of industry practices, claiming that the context and purpose of school is so divergent from that of business it makes meaningful transfer impossible. As always, I disagree with that position. We can learn a great deal about skill development from business, including the learning model advocated by a software development company called Callibrity.

Callibrity, like most modern companies, expends vast energy and resources on developing the skills of its workforce. The recommendation list for its employees could easily be adapted to a K-12 or higher ed context.

- Play: Employees should use a percentage of their regular work time to explore new areas of interest alone or with teammates.

- Listening: Reading within that area of interest or participating in informal sessions (lunch-and-learn, in industry lingo) are encouraged.

- Apprenticeship: Mentoring programs or even informal access to a mentor should be encouraged.

- Classes: Online or face-to-face training in skill development is encouraged.

- Pairing: A study buddy interested in the same skill enhances the process of learning.

- External Expertise: Call in a staff development specialist, community member, or expert who can supplement instruction focused on a targeted skill.

Clearly, there are stages to skill development for both adult and young learners. Clearly, we must offer multiple opportunities to develop and hone these skills over time. Trial and error are integral to the process.

We return to our original statement. There is broad consensus on the skills that all learners need to be successful in college, career, and community. That consensus has even breeched the formerly impenetrable wall of federal education policy via the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). These skills, now unleashed by the tulip fever for social-emotional learning, must be taught and assessed. That process should be governed by what we know about how learners develop skills. Let’s all get up and do the wave.

For more see:

- Schools Really Can (and Should) Measure Noncognitive Skills

- Teachers Deserve Better Tools for Tracking Sub-skills

- Getting Smart on Assessing and Measuring Social and Emotional Learning

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.