David Weinberg on The Art of the School Visit

On this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, New Pathways Senior Fellow Trace Pickering is joined by David Weinberg, a teacher, principal, curriculum director, assistant superintendent, and a founder of EPIC North HS in New York City. He now spends his time working to help schools become more innovative and restorative.

Trace Pickering: All right, you’re listening to the Getting Smart Podcast. I am New Pathways Senior Fellow Trace Pickering, and today I am joined by David Weinberg. Welcome, David!

Dave Weinberg: Good afternoon, Trace. It’s really nice to be here.

Trace Pickering: A little bit of background on Dave. Dave’s been working as an educator for over 20 years. He believes deeply that education is the greatest tool to impact social change and level the playing field for all people. He’s been a teacher, principal, curriculum director, assistant superintendent, and, in his spare time, founded Epic North High School in New York City. He now spends his time working to help schools become more innovative and restorative. I met Dave several years ago when he came to our Iowa BIG school with a visit team from a group called Springpoint. I was immediately impressed both with Dave and the site visit process that Springpoint so masterfully uses. Since then, Dave has been to our site twice on visits, and I now have the privilege of working with him as a teammate on Springpoint visits around the country. Matter of fact, we were just together in the last couple of days on my first site visit, where he was the lead.

The reason I wanted to talk to you today, Dave, is that I know you’ve seen hundreds of schools up close and have a unique perspective that we really want to tap into here on Getting Smart to discuss what works and what doesn’t. So, we’re excited to have you here. Is there anything you’d like to add about yourself that I didn’t cover?

Dave Weinberg: That’s a beautiful intro. Thank you. I think the bio you have for me is a bit out of date because I’m actually over 20 years in education now, which probably just means I’m getting old.

Trace Pickering: I wondered; 17 didn’t quite add up! Do you have a sense of, roughly, how many schools you’ve been able to visit and see over your career before Springpoint and after?

Dave Weinberg: No specific number, but I think you’re right—it’s definitely in the three digits, which is pretty intense if you think about it. And I realized as you were saying that, it’s a really unique perspective. Most educators are pretty place-bound, and even if they visit other schools, it’s usually within a city or state. One of my favorite things over the last four or five years, pandemic excluded, of course, is getting to see schools all over the country—in Northern Maine, Yuma, Arizona, and everywhere in between. It’s been incredibly powerful and rewarding.

Trace Pickering: How did you pivot into this work? I know you do consulting and other work, but what led you to focus on these site visits with Springpoint? It’s an intense amount of work but wonderful work.

Dave Weinberg: Well, when I left the school I founded in New York City, I had a real urge to see what was happening elsewhere—just personal curiosity. Founding a school is like giving birth; the first four years, you can do nothing but focus intently on your school. As soon as I left, I was curious to see how our work compared to others and what other places were doing that was new, interesting, or innovative. But I didn’t really have a professional reason to do it; I was coaching principals and working with some districts. I reached out to everyone I knew in education, expressing my interest in visiting schools. One of my first visits was simply on my own to a district outside Pittsburgh doing innovative STEAM work. They welcomed me in, and it was powerful.

From there, things evolved. My school had been a Springpoint visit school, a destination for many visitors passing through New York to see innovative practices. So, when Springpoint started organizing on-site visits, they reached out to me, and one thing led to another. My first Springpoint visit was in California at Summit Shasta, an XQ school, and it’s been rolling from there. I love the work because it involves everything I wanted to do—talking to students and teachers, learning about what’s happening, and providing feedback and support.

Trace Pickering: That’s awesome. And that’s how we met too—through an XQ visit with Springpoint at Iowa BIG. Just quickly, I remember that first visit. When you came in, I sensed you were a healthy skeptic, maybe doubting whether we were truly doing the things we claimed. But the next day, that skepticism seemed to vanish, which was fun to see.

Dave Weinberg: Ha, it’s great to know I give off a skeptic vibe. I am generally skeptical, especially when it comes to school claims. When I visited Iowa BIG, most innovative spaces I’d seen were education-adjacent, like after-school programs or maker spaces that weren’t tied to traditional schools or districts. As soon as something is called a school, expectations shift, and a lot of the innovation disappears under the weight of traditional school paradigms.

Trace Pickering: My first real question for you is, what are some of the more encouraging things you’ve seen as you’ve traveled across the country visiting hundreds of schools? What gives you hope that we can transform education in this country?

Dave Weinberg: I’d say the most encouraging thing is the number of people across the U.S. still committed to the idea that education can do great things for young people. I’ve never been to a school where I didn’t meet at least a few people still fighting that fight, still dedicated to helping kids go places. That kind of dedication, especially when it’s clear folks are tired or frustrated but still bringing it every day, is incredibly inspiring.

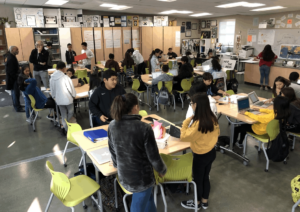

Another hopeful trend is seeing schools create a sense of belonging, purpose, and curiosity among young people. There’s research that points to these three elements as crucial, and I’ve seen schools that manage to foster one or more of them effectively. At Iowa BIG, for example, I saw the possibility of a truly student-centered curriculum. One story that stands out to me is when I met a sophomore who was researching the impact of positive attitude on cancer survival because her dad had survived cancer. She was about to call a Harvard expert to discuss her findings, which was mind-blowing. She and her team were deeply engaged, curious, and supportive of one another—a great example of what education can look like.

Another thing that gives me hope is that students know what they need and want. In every school I’ve visited, students have clearly articulated what’s working for them, what’s not, and how they envision their future. Their ability to call out what isn’t working and articulate their goals is a huge bright spot.

Trace Pickering: So you’ve seen belonging, purpose, and curiosity happening in schools, but is it common to see all three working together?

Dave Weinberg: I’ve never seen a place where all three are working perfectly in tandem, though that doesn’t mean it’s impossible. More often, I see schools excelling in one area, which then supports the others. For instance, a school with a strong sense of belonging may leverage that to build purpose, or one focused on purpose might inspire a sense of belonging among students. But I haven’t yet seen a school that’s perfectly well-rounded in all three areas.

Trace Pickering: You also get to spend a lot of time talking to school leaders on these visits. What patterns have you noticed among leaders who are close to achieving these three elements? Are there specific skills or qualities that set them apart?

Dave Weinberg: The first thing is that successful leaders understand the limitations of the system and work to protect what they’re building from those limitations. For instance, at Iowa BIG, you all designed the school with a clear understanding of the “game of school” and how to shield innovative practices from it. Great leaders know how to balance and protect their vision against external pressures.

Additionally, they are excellent storytellers. They tell the school’s story in a way that everyone—staff, students, and new hires—can buy into. This shared narrative helps unify the community around a common mission.

Trace Pickering: When you first enter a school, what are the initial things you look for or notice, and why?

Dave Weinberg: The first thing I look for is how students are greeted. If there’s a metal detector and police officer, that sends a certain message. If they’re greeted by a friendly adult with a smile or a high five, that sends a very different message. I also pay attention to how much students own the space. If students are welcoming or ask questions about what I’m there for, it’s a good sign of student ownership.

I also consider how well the school reflects the community. When a school feels deeply connected to its local context—like Crosstown High in Memphis, which is integrated into a community center with student art everywhere—it creates a strong sense of place and belonging.

Trace Pickering: What are some non-examples or common issues you see in schools that struggle to move forward?

Dave Weinberg: The main issue in struggling schools is often an absence of trust. When there’s a lack of trust between students, teachers, and administrators, it creates a toxic environment. I’ve seen schools where the focus is heavily on external incentives, punitive discipline systems, and an overemphasis on control. In such schools, students and teachers feel unsafe to take risks, and the environment is demoralizing.

Another problem is that these schools often rely on traditional, punitive justice systems. They prioritize controlling behavior over fostering a sense of belonging or agency, which makes it hard for students to feel like they belong. For instance, many schools adopt a “restorative justice” model, but if an adult isn’t willing to reflect on their own actions or beliefs when a student raises concerns about something like bias or unfair treatment, then it’s not truly restorative. Schools need to be spaces where adults are willing to adapt and self-reflect, but that’s a big ask, especially in environments that are already stressful and challenging.

Trace Pickering: Right, and what I’m hearing is that a lot of these issues come down to control. Adults in the system often try to over-control, but true leadership is more about influence than control. Over-controlling leads to negative outcomes and poor decisions.

Dave Weinberg: Exactly. Real transformation requires adults to shift their own mindsets, which is challenging. For example, I often see schools say they’re committed to “restorative justice,” but when it comes down to it, if adults have to make personal changes or face feedback about their own biases, they’re not always willing to do so. Being truly restorative requires a level of psychological safety, reflection, and willingness to evolve that isn’t easy for anyone.

Trace Pickering: This pivots nicely into the last segment of our conversation. I’ve told you this before, but on the receiving end of many site visits, I often felt beaten down or, at best, that my time was wasted. That was the opposite of my experience when you and the Springpoint team visited us, and I saw that same approach again this week. You had to deliver both great feedback and some challenging reflections to the school, and you all did it in a way that was supportive. What have you learned about giving feedback effectively, especially when it’s tough feedback?

Dave Weinberg: Well, first of all, I’ve been on the receiving end of many visits that didn’t work well, so I have a big mental checklist of what not to do. For example, once in New York City, I was outside greeting students, and someone walked up and introduced themselves as my new boss, without any prior heads-up. That experience taught me a lot about the importance of humility and openness.

One of the first things I try to do on a visit is acknowledge that I’m an outsider and that I don’t know everything that’s going on in the school. It’s essential to walk in with an open mind, free of assumptions or rigid checklists, because if you come in with a preconceived agenda, you risk missing the unique strengths that the school may have.

Another thing is empathy. You and I were just on a visit with a colleague who said, “My empathy is through the roof right now,” which is exactly the mindset I try to maintain. Schools are tough places, whether you’re in your first year or your twentieth, so it’s important to approach each visit understanding that everyone is likely doing their best under difficult circumstances.

Trace Pickering: Absolutely. It struck me as you were talking that one of the things we did this week was score a rubric, but only after we’d gone through all the data and discussions. That approach felt different from what people might expect.

Dave Weinberg: Yes, exactly. The rubric is a tool we use at the end to make sense of the data and observations we’ve gathered. But first, we talk through everything we saw, discussing patterns and insights. That way, we don’t force the data to fit into the rubric categories prematurely, which often happens in more compliance-driven visits.

Another important part of the process is giving space for feelings. Schools are places where both data and emotions matter. If we don’t give space for staff to express their feelings—whether that’s frustration, pride, or anything else—those emotions can influence how they interpret the feedback. Giving people room to express themselves helps ensure that we’re all on the same page and can move forward together.

Trace Pickering: Right, and creating that space for emotions helps people feel heard, which can make them more open to hearing feedback. I can’t believe our time is already up, Dave. It’s been great talking with you. I appreciate you taking the time to share your insights with us on Getting Smart today.

Dave Weinberg: Thank you so much, Trace. And I just want to add that if listeners don’t know much about Iowa BIG, they should definitely check it out—or even book a flight to Cedar Rapids! I don’t want to overwhelm your former school with visitors, but Iowa BIG is a fantastic example of a place that builds curiosity and fosters real learning. It’s been a privilege and an honor to join you today.

Trace Pickering: Thank you very much, Dave.

Dave Weinberg: All right, thanks, Trace.

For more with Trace Pickering:

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.