Processes and Principles for Public Schools Navigating Uncertainty and Adapting to Change

By: Eric Tucker, Ashley Deal, Raelynn OLeary and Sarah Pactor

Experts from around the world are encouraging schools to prioritize safe, in-person options for families through the coming winter months. Food and housing insecurity, childcare needs, workplace instability, mental health and wellbeing concerns, the limitations of fully virtual options for some students, and the need for essential services inform these recommendations. Educators are being asked to lead through a period that lacks easy answers, where technical solutions are insufficient. How can schools better navigate this uncertainty, and come together to adapt and respond to the dark winter that has fallen?

It was May, a few months into the pandemic, when the Brooklyn LAB leadership team realized it was time to rethink school in order to adapt to the seeming realities of re-entry and resurgence. With cases rising and no hope on the horizon for controlling COVID-19, the school faced the daunting task of planning to provide education using some combination of remote, hybrid, and in-person learning. At the same time, it felt impossible to plan anything: In addition to the pandemic, the country faced a looming economic recession, ongoing reckoning with institutional racism, and a deeply polarized political climate.

There was no way to know how many students and teachers would return to school, when, and what kind of challenges they would be coping with when they did come back. At Brooklyn LAB, about 30% of students, which LAB calls “scholars,” have special education needs, and many struggle with learning due to a variety of social and emotional issues. The school has created a special environment that caters to the most vulnerable students, and the education team wanted to ensure their success, especially during this crisis. But how?

Brooklyn LAB decided the best way forward was an intensive design process that involved the entire school community. To help lead this design process — and create resources to share with other schools — the school engaged Dezudio, a small design consultancy in Pittsburgh.

In addition to running Dezudio, the principals of the studio, Ashley Deal and Raelynn O’Leary, teach in the Carnegie Mellon School of Design, where their students were grappling with canceled internships and an uncertain future of work. As it was for everyone during the pandemic, stress levels were high, and life was just harder. This is where we were when we embarked on the process to reimagine education at Brooklyn LAB in the middle of a pandemic. It may be unusual to share our backstory, but we do this because it highlights one of the key principles of our project: To create solutions that work for all, we need to understand the real-life challenges people are experiencing, including our own as education leaders and designers. This helps us build the empathy we need to find solutions that work.

Through all of it, we were committed to doing right by our students—to providing them with the educational and emotional supports they deserve every day and especially during this most challenging time. We hope that by sharing our approach to inclusive design—what we did and what we learned—other education leaders will find inspiration to learn and adapt personally and professionally in a time when we are all being called to navigate uncertainty and adapt to change.

What We Did: The Brooklyn LAB Process to Reimagine Education in a Pandemic

The purpose of our project was to reimagine education in a pandemic, and our goal was to make sure whatever solution we developed supported the needs of all of our students and staff, including those who are most vulnerable to the impacts of COVID-19 and to the ongoing systemic challenges build into our system of education.

Our process involved five steps:

1. Constrain the space and focus the challenge.

Reopening plans, contingencies, and communications had to be in place within a matter of weeks, and there were so many different angles and details to consider in that short period of time. LAB decided to orchestrate a series of design charrettes to bring teams of experts together to work in short bursts to tackle specific parts of the overall challenge. Experts gave initial presentations on their area of expertise as it related to the topic (facilities planning, instructional scheduling, success coaching, identity and agency, etc.) to LAB staff, and worked with Dezudio designers to create a cohesive, shareable product.

2. Bring a variety of viewpoints to the table.

We wanted to make sure we had the right expertise to help assess the issues and offer perspectives on solutions. The School engaged family members, students, faculty, and staff members. LAB also tapped into its strong network of partnerships with related organizations to bring in the foremost experts from education and related fields. These organizations are specialists in school architecture and classroom layout, teacher staffing and development, educational equity, trauma-informed learning, and creating cultures of success in schools.

3. Create and share scenarios.

Each charrette produced tactical plans and ideas for the School to execute during reopening, and we also prepared a final presentation that distilled and refined each partner’s thinking in a way that was accessible to a variety of stakeholders, including teachers, staff, families, and students. Through focus groups, town halls, surveys, interviews, solicitation of feedback and edits, and design jams – the input of school community stakeholders was solicited and integrated into revised versions.

4. Focus on preparation over planning.

Early on, the school vowed to do this process differently, in a way that accounts for flexibility and adaptation. Historically, education, like many other domains, has been prone to creating static plans that become quickly outdated. Preparation, by contrast, anticipates multiple scenarios, accounting for context, conditions, and learning. With a focus on design-based preparation instead of traditional planning, we build the muscles we need to adapt and determine the right next step. To shift our focus to preparation, we applied principles of Universal Design for Learning to the preparation process, were intentional with seats at the design table, and sought to identify and learn from bright spots. We considered multiple scenarios in parallel, iterated between external guidance and operational components, and emphasized improved communications.

5. Prioritize the needs of the most vulnerable.

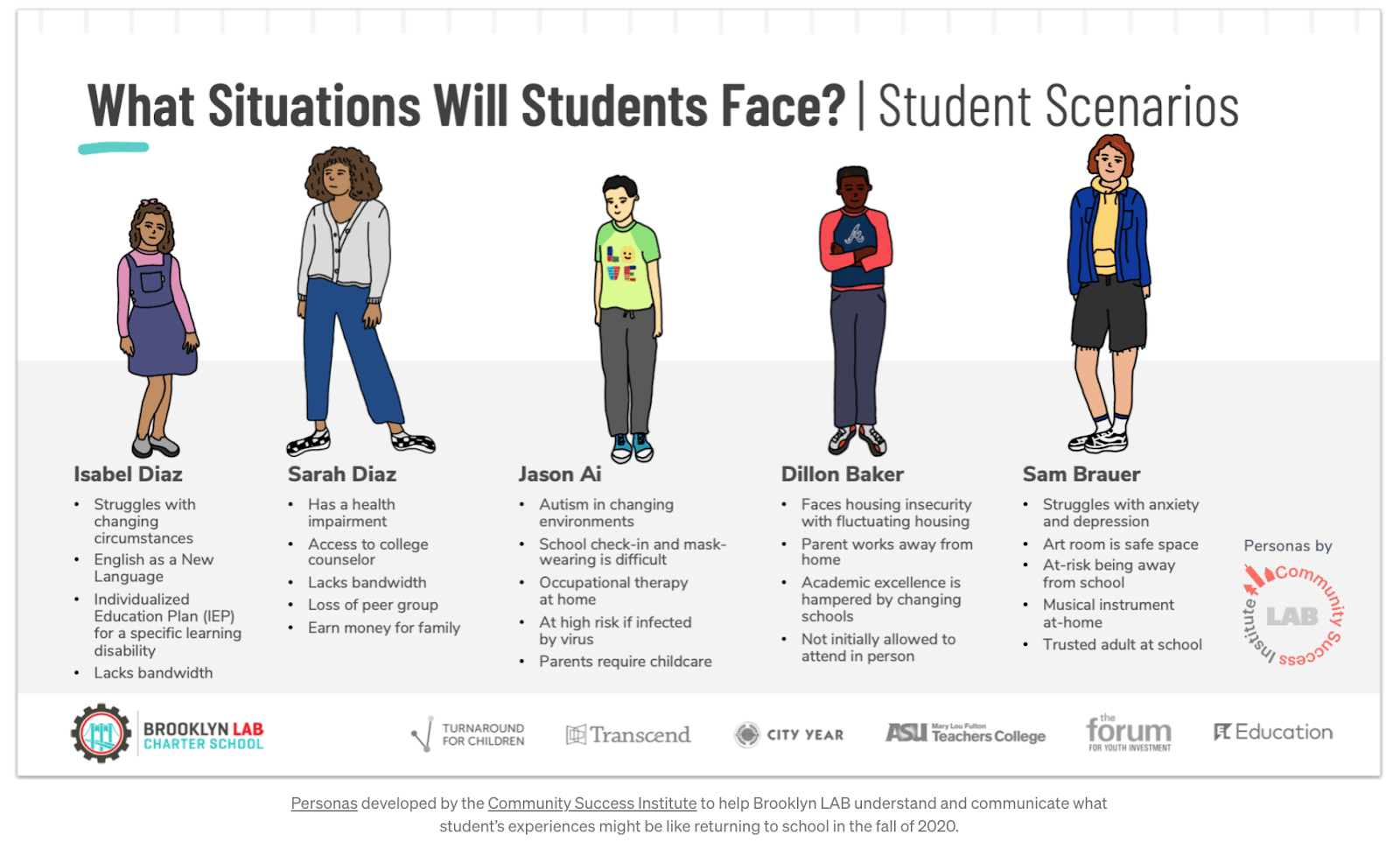

Schools too often make plans for the “average student,” focusing on the mythical 80% of average students with the idea that we’ll figure out how to address the needs of the others down the road. While that may seem like an efficient strategy, there is no “average student,” so we’re actually creating more work for ourselves and dramatically increasing the chances that significant numbers of people are left behind. In this process, we prioritized the needs of the most vulnerable students by asking questions such as:

- How will we support students who struggle with attention or impulse control, who may be unable to comply with public health requirements?

- How will we stay safe and support students who may struggle with emotional issues, as they potentially experience more frequent or uncharacteristic discipline outbursts?

- How will we conduct speech therapy or work with a student who is hard of hearing when we are all wearing masks? How will students who struggle with social-cognition understand teacher and peer cues through masks?

- How will we ensure safety and learning for students who may have experienced extreme trauma or adversity?

The reality is that by expanding our consideration for those on the margins, we’re actually improving things for everyone across the board.

What We Learned

Above all, this process affirmed the importance of empathy, for our students, our staff, and ourselves as school leaders and designers. It also taught us other critical lessons:

This was a new situation, but we still had the same core goals: We found ourselves in a situation where we were trying to accomplish the same things we always have, but in new and different contexts. We learned that it’s critical to step back and consider both our contexts and our goals and decide what activities can be optimized in what channels. It also meant determining what is most important. For students, it meant paying special attention to their social and emotional well-being. For teachers, it meant not leaving behind core activities like mentorship, collaboration, planning, team-building, and leadership development.

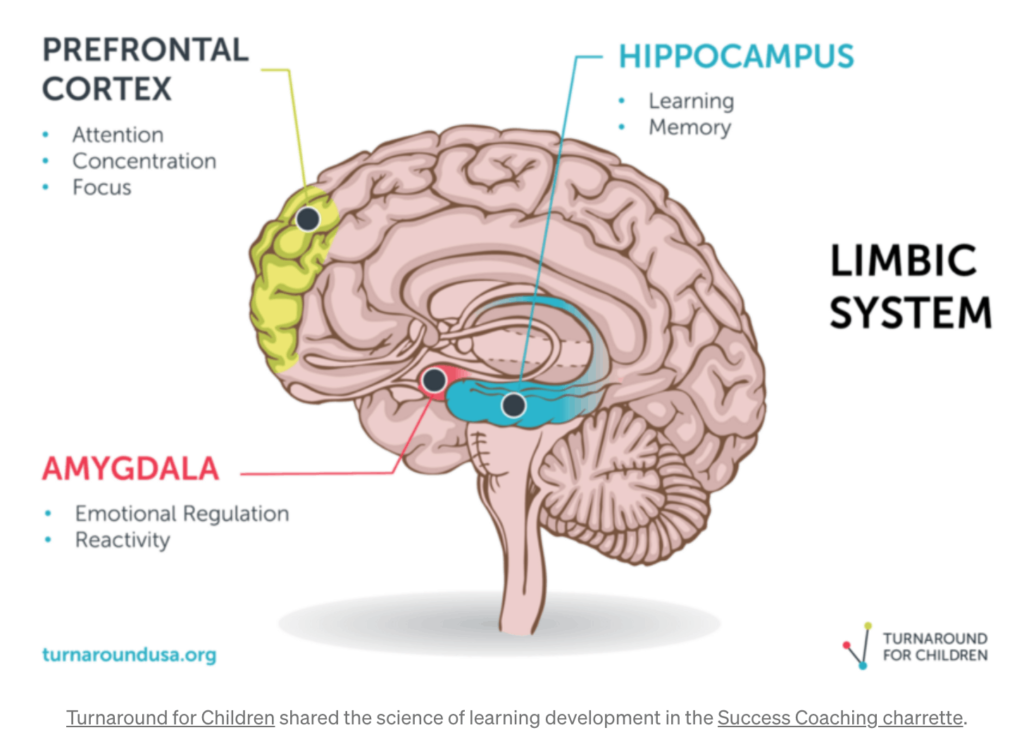

Social and emotional needs form the foundation of learning: Many educators may enter the process to reimagine school thinking that this will be about the technical and logistical aspects of school: What’s needed to ensure access to technology from home or to maintain social distancing in the classroom. But our design charettes reminded us that social and emotional needs are critical to learning, particularly during times of crisis. From our work with Turnaround for Children, we learned that human relationships are the antidote to stress. In other words, adversity doesn’t just happen to children; it happens inside their brains and bodies through the biologic mechanism of stress. Relationships that are strong and positive cause the release of oxytocin. This not only helps children manage stress, it offsets the damaging effects of cortisol and produces resilience to future stress.

Considering collective impacts is as important as focusing on specific challenges: While we focused on smaller aspects of challenges during the design charettes, we learned that with so many moving pieces, it was also important to keep our eyes on the cumulative impacts of decisions. Often things that seem simple and direct in isolation can become complex and overwhelming when they all add up. Design tools and methods, such as this set of student personas created by Community Success Institute, helped us understand how our decisions would affect different students and families in real life.

Balancing empathy for frustrations with hope for opportunities cultivates creativity: Historically, when faced with challenges, we have tried to reframe them as opportunities. While this frame is positive and often productive, reframing a global crisis as an opportunity feels a bit disingenuous. But we found that the key is to hold space for the frustration we feel about circumstances that are beyond our control while finding ways to do the best we can given our current circumstances. We know constraints often foster creativity, so we can strive to keep an eye out for opportunities within these new constraints.

We feel good about the work that we collaborated on, the tangible interventions Brooklyn LAB has been able to implement, and the principles we developed that will help guide our decision-making well into the future. We learned from and collaborated with inspiring people throughout this process. If you’re interested in more detail about any of the processes and principles we’ve discussed, visit equitybydesign.org/processes-and-principles. If you’d like to learn more about the ways that Brooklyn LAB is working to keep equity at the core of everything we do in these fluid times, we hope you’ll check out our other projects at equitybydesign.org.

For more, see:

- Processes and Principles for Navigating Uncertainty and Adapting to Change

- Five Principles to Help Provide Our School Communities with the Communications They Deserve

- Educating All Learners Alliance Launches Flagship Site, Shares Personas Educators Can Use to Understand Students’ Lived Experience During COVID-19

- How We Move Forward: Practicing Three Inclusive, Anti-Racist Mindsets for Reopening Schools

- Preparing to Reopen: Six Principles That Put Equity at the Cor

- Preparing for a Healthy and Safe Return to School: Public School Facilities Planning in the Era of COVID-19

- Schools Need a Success Coach for Every Learner

- To Reopen, America Needs Laboratory Schools

- How to Reopen Schools: A 10-Point Plan Putting Equity at the Center

- Reopening Schools: A Scheduling Map for Educators to Plan the Who, What, When, Where, and How of Learning this Fall

Ashley Deal: Information and interaction designer; design researcher. Partner at Dezudio and Adjunct Faculty at CMUDesign

Raelynn OLeary: Information and interaction designer; design researcher. Partner at Dezudio and Adjunct Faculty at CMUDesign

Sarah Pactor is a senior project associate at Friends Of Brooklyn Laboratory Charter Schools

Dezudio is a small design consultancy with offices in Pittsburgh and Washington DC. Partners Ashley Deal and Raelynn O’Leary teach in the School of Design at Carnegie Mellon University.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.