One School’s Experience with Distance Learning: Why Personalized Learning Is The Way Forward

By: Zach Varnell

On March 13, 2020, along with approximately 1.5 Billion students across the globe, we closed our school and dove headfirst into ‘distance learning.’

What we as a school decided on in those first few weeks was that more than anything, students needed anything that resembled normality. Teaching is a highly relational act, and if we couldn’t be there in person we knew that our students wanted at least to see their teacher’s faces every day. They wanted a personal experience, not a PDF of a lesson plan or a worksheet. We had an opportunity to be creative and if we had one goal we could measure it was engagement. At least we could try and see if we keep our students connected and excited about learning.

It became clear in Washington State that learning needed to continue, but grades could no longer be a motivating factor. No one was going to fail. On one hand, this was a great opportunity: how could we as educators engage students when it didn’t matter on their transcript if they did or not? Would they learn to love learning, simply for the sake of learning itself, or would they disappear into the virtual cloud? Furthermore, would they even have the ability to engage in distance learning? Did they have the technology, were their daily responsibilities suddenly consumed by taking care of their siblings if their parents or guardians had essential jobs? Were they working now to help make ends meet? Did they even know how they were going to make ends meet?

What’ve We Learned

With all this mind, we built a framework early on that showed some promise, at least in the short term. We built a singular landing page for our entire school and leaned on our PLC’s to develop only one lesson per week to simplify expectations, with a few ability levels to choose from. We committed as a team to stay away from simply posting worksheets and PDFs of lesson plans and started filming short ‘video intros’ for each lesson hoping to engage students through enticing video content. After all, students just want to see their teacher’s face, right?

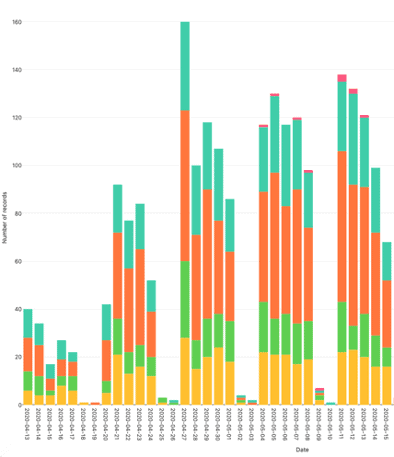

We also built a rough log-in tool to track student engagement. At least students could tell us if they were there each day and we could keep a record of who was clicking through and who wasn’t. Through mentor groups, we then shared that weekly data with mentors so they could follow up each week with the list of kids who hadn’t checked in. We were lucky in that we had these structures in place to check in with every student without bombarding them with six daily emails from each teacher. This showed some promise and we started to see some weekly growth in engagement, at least as we were measuring it by logging in.

We were looking at weekly growth of unique logins, as we worked tirelessly to connect with students and made sure they had laptops, that they knew how to access the landing page and knew what each day of the week was assigned to. I’m sure you can look at the graph and see which day it was announced that attendance would be officially recorded.

Is This Learning?

It’s certainly encouraging to see growth in data, especially when it’s measuring potential ‘engagement,’ but there’s no question that simply getting students to click on a website is a far cry from measuring a progression of learning towards mastering a standard. In a traditional classroom, we measure engagement through formative assessment, not merely attendance. Also, there are always barriers to accessing learning in a physical setting, some of them being technological or sometimes even physical, but in a virtual environment those barriers are exaggerated and many times even more difficult to assess.

Differentiation is also a challenge, even with articulate scaffolding. As an administrator, I was blown away by the creativity and willingness of our team to try any and everything to keep students engaged, but it also became clear very quickly that actual learning was harder and harder to measure.

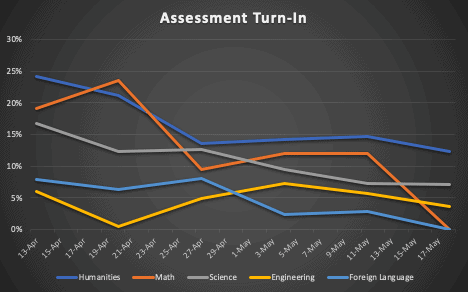

A handful of our PLC team leaders started trying to track assessment data and share that with mentors so mentors could focus on accountability and encouragement; that’s how our model works during a normal school year. This data became far less encouraging and ultimately, we gave up trying to collect and continually sort a massive shared spreadsheet of standards, evidence, and progress. We settled on simply tracking whether or not students turned something in for formative feedback, one step above simply counting if they showed up to the landing page or not. Even that data provided a bleaker picture than what our initial data suggested.

Over the course of six weeks, every content-area PLC saw a steady decline in work turned in for feedback. Some of this can of course be attributed to the fatigue of distance learning combined with the settling in of the realization that none of this will count towards high school credit. Teachers in turn have also shared the fatigue with working to develop lessons that are engaging and creative, finding ways to differentiate for the materials and technology students have access to and yet still seeing a slow and steady decline of interest. It starts to feel like you’re teaching into a void.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Along with the literally billions of other students around the world with no idea what to expect from school this fall, teachers are trying to plan for a scenario that is anything but defined. There is certainly an opportunity to rethink what school could look like, with an added push to move away from the standardized and singular focus of academic measurement that drives so much of secondary education (and in turn inequity in academic achievement). If there’s one thing this pandemic has revealed is just how inequitable these measures really are. Horror stories of students racing to finish an online AP test before a borrowed laptop battery dies because their power was shut off at home or even having to wake up at 4 AM to take an online test that was only offered during a certain time in name of “universal fairness” (but certainly not equity). These may seem like more extreme examples, but the inequities have always been there, they might just be more visible now.

As one district administrator from Ohio shared at A New Way Forward in April, “I’ve certainly never met a child who doesn’t have hopes and dreams” yet somehow we have “turned public education into buckets of compliance that need to be filled.” It will not be possible for this change at the secondary level until post-secondary institutions begin relying on the same measurement tools and institutions to tell them who is qualified to move on to higher education and who is not. There is a glimmer of hope even in this, as California State’s largest university system recently announced it would phase out using SAT and ACT test for admissions.

The measurement tools for achieving mastery of learning certainly exist and there is no shortage of research of assessment strategies that point educators towards individualized learning and measurement of progress. We need to develop the tools to create an individual pathway to post-high school achievement that centers on multiple intelligences and focuses on the relationship between educators and students. What the past eight weeks has taught us, at least in our building, is that every student needs an individual academic plan and needs to play an active role in laying out what that plan looks like, what they will be measured on and what supports they will need to achieve it.

For decades we have tried the carrot and stick approach, by dangling graduation above students’ heads and hoping they will care enough to jump through all of the hoops to get there (some of those hoops will be large and some will be much, much smaller, depending on the student). For the last 8 weeks we’ve been forced to try the ‘Tiktok approach’ by trying to capture students’ attention and hoping that will interest them enough to learn for learning’s sake. For this next phase to work, we have to let students tell us what they want to achieve and then help them craft a path towards that goal and hold them accountable to achieving it along the way. We have to guide them towards their goals while scaffolding what the world will expect from them into manageable steps. If we don’t, this next phase will even further the gap that divides those that have access to a future and those that don’t.

For more, see:

- Getting Through: Leading Through and to a New Generation of Learning Systems

- Personalized Learning is a Transformative Idea Without a Transformative Technology

- Preparing to Reopen Six Principles That Put Equity at the Core

Zach Varnell is the Co-Director of IDEA High School in Tacoma, WA.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

We know that educators and leaders have spent the last couple of months scrambling to meet the immediate needs of learners in their community. Thank you to each and every one of you for everything you’ve done to make the best out of this challenging situation. Now that the end of the school year is here, we’re shifting our Getting Through series from stories and advice to support remote learning or long term closures, to getting ready for the complex work of reopening schools this fall.

Interested in contributing to this campaign? Email your stories and ideas to [email protected] or tweet using #gettingthrough to participate!

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.