Project-Based Learning in Lights, Camera, Action

By: Paul F. Brown

The typically peaceful field behind our school seemed more like the backlot of a film studio that week, as groups of my students spread throughout the park to shoot scenes for their final projects—five-minute movies that they produced themselves.

These projects fell at the end of a semester-long study of filmmaking, during which students had built up a vocabulary of film terms and techniques based on class lectures, representative films, and hands-on photo and video projects.

For example, after learning about types of camera movement, students viewed film clips like the opening scene from Touch of Evil, a complex and continuous shot that combines crane, pan, tilt, dolly and tracking movements. Using their smartphones, students then went outside and captured video of seven different camera movements and later joined the clips together using a video-editing app.

Over the first 12 weeks of class, students became familiar with shots, angles, lighting and color schemes, and compositions. They learned about the development of motion pictures from silent to sound, black and white to color. They studied classic films of various genres, like Modern Times, Singin’ in the Rain, and Rear Window.

Now approaching week 17, students were demonstrating their understanding of film techniques—but not through a written final exam. They were scripting, directing, acting and editing their own short movies. But how well did this major assignment conform to the Framework for High Quality Project Based Learning (HQPBL)?

Intellectual Challenge and Accomplishment

Students could choose any topic for their project as long as it was meaningful and presented in a class-appropriate manner. So their stories did not necessarily have to explore “a complex problem, question, or issue with multiple answers,” as the framework specifies. Last semester one group’s project addressed two heavy subjects, bullying and the loss of a parent, and handled both with maturity. But allowing students to choose the topic naturally resulted in a variety of genres, from drama to suspense to comedy. This semester’s groups leaned toward the latter, such as one storyline that involved a goat-headed creature hunting for beef jerky. Regardless of the chosen subject matter, this month-long film project presented its own set of “complex problems,” which students solved in multiple ways.

Authenticity

Movies are a big part of the students’ culture and conversations, and perhaps the primary way students experience storytelling. But they consume films uncritically, with little awareness of the ways filmmakers manipulate the audience. A study of film and filmmaking helps students better understand and communicate about the movies they see. It also shows how films are a powerful form of communication, giving voice to ideas and messages more clearly than words alone can express. In addition to showing “what happens in the world outside of school,” as the HQPBL framework mandates, the project raises practical issues, like the aesthetic choices students make (often subconsciously) when taking photos and videos on their own smartphones.

Public Product

Students knew from the start that their projects would be shown in class and to keep the audience in mind as they created their films. Although groups received feedback from me at each stage in the process, their projects did not become public until the final presentation. According to the HQPBL framework, public sharing should occur “during the project,” not just at the end. I could have initiated this through regular workshop sessions, where each group shares its in-progress work—story ideas, script drafts, even raw footage—with the rest of the class. Overcoming the initial fear of presenting unfinished work, groups would come away from these sessions with helpful input on the effectiveness of their projects and how best to proceed.

Collaboration

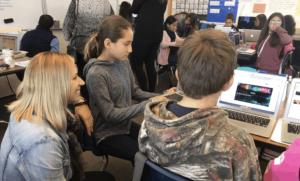

Film is a collaborative art, as confirmed during the end credits of any movie. At a bare minimum, this project required a scriptwriter, a camera person, an actor, and an editor, though one student could fill multiple roles. Not all students embrace collaboration. One group struggled this semester because none of its introverted members took charge of the project. They didn’t verbalize their ideas, their script came together at a snail’s pace, and they turned in their (subpar) film late. Knowing their passive tendencies from previous assignments, I should have placed each of these students into groups where they would have specific roles to fulfill and be encouraged to participate. All of the other groups discussed their ideas, stayed on task, and used their time efficiently. The HQPBL framework recognizes that collaboration is a necessary, real-world skill.

Project Management

The ability “to manage time, tasks, and resources efficiently” is equally important. Students were more likely to use time well if they had a plan. At each step in the filmmaking process—from brainstorming story ideas, to writing the film treatment, to drafting and revising the full script, to keeping an updated shooting schedule—they had to have the end goal in mind. But even with careful preparation, some groups experienced setbacks and delays. Students had to solve problems in real-time, like how to carry on when a key person in a scene is absent one day, or forgets to bring an important prop (say, a large goat mascot head). Project management is key to meeting guidelines and finishing on time.

Reflection

The HQPBL framework also states that, like public sharing, thoughtful reflection should occur throughout the project, not just at the end. While groups took stock of their daily progress—what worked and what didn’t—they weren’t asked to reflect deeply on their learning experiences until the final day of the project. At that time students completed a formal, written reflection and also assessed their own participation and that of the other group members. Had I implemented “public” workshops during the project, as suggested earlier, self and peer reflections would have been natural components of those sessions. When students think about their learning at each phase, the framework says, they “develop a greater sense of control over their own education, and build confidence in themselves.”

These students attend a Title One school in rural East Tennessee. Several years ago, the school system purchased Chromebooks for all of its high schools, and since then has added more for grades four through eight. Students now have easy access to Google’s educational apps, but still, lack the sophisticated video editing software that comes standard on Apple products. They’ve had to make do with using apps like iMovie on their smartphones or editing with a free version of WeVideo on their Chromebooks.

While frustrating, we viewed the situation as yet another exercise in problem-solving. How can students produce high-quality projects despite budget limitations? A good story and well-planned script are essential starting points. From there, it’s all about making the audience see exactly what you want them to see. I reminded students to make something they would be proud to show others. (Also essential: Shoot in landscape mode so your video doesn’t look like skinny, vertical cell phone footage.)

In the three semesters I taught this course, students surprised me with their creations. The best feeling as an educator is when students take what you’ve taught them and run with it. When they play the game and try their very best, it’s magic.

For more, see:

- 4 Ways Project-Based Learning Prepares Students For the Future of Work

- Four Mega Trends Reshaping Global Learning

- Students Learn Project Management From HQPBL Experiences

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

Paul F. Brown taught K-12 music for ten years. As a freelance writer in Knoxville, Tenn., he has published articles and authored an award-winning biography, Rufus: James Agee in Tennessee. Learn more about his work at paulfbrown.com.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.