The Educational Implications of Michelle Obama’s Becoming

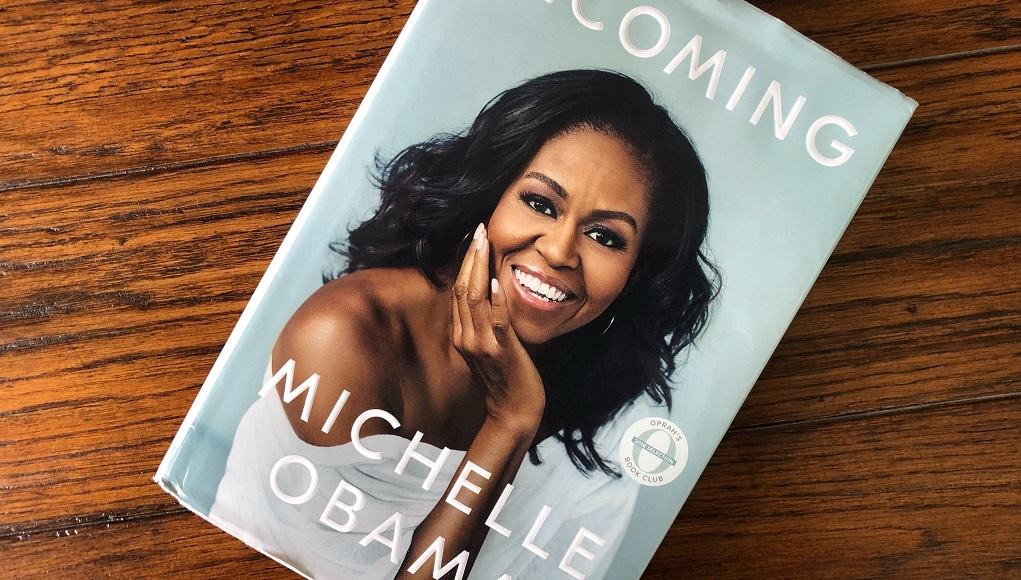

Michelle Obama’s life story, in so many ways, is extraordinary. She came from the South Side of Chicago, grew up with working class parents, attended public schools, graduated from Princeton and Harvard Law School, was an Assistant Dean at the University of Chicago, and became a Vice-President of a medical school. And then she reoriented her professional and personal life to serve as the First Lady of the United States for eight years. Her biography entitled Becoming, published in November 2018, has now sold in excess of ten million copies. Extraordinary indeed.

As we each read Becoming, we sought to understand which factors, life events, and support systems were involved in Michelle Robinson becoming the impressive, impactful, extraordinary Michelle Obama we know. As Michelle’s story unfolds in the pages of the book, it became clear that education, and the manner in which her education was supported, played a pivotal role in this story.

Above all, Michelle’s experiences in and around school reinforced that she inherently has value simply because she is a human being. Michelle’s parents instilled in her that her future was worth the hard work and effort. She was taught that there was no ceiling on the level of attainment she could achieve. Michelle was empowered by her teachers to use her voice and have agency in driving the course of her own education and future. Her mentors showed her that she had strengths she, herself, did not even realize. Parents and mentors ensured that she was in classrooms and community activities that reinforced this positive developmental expectation and provided her with structured experiences to pursue her interests and be challenged to excel. And, as she grew and matured, she realized that her skills and talents could help both sustain her own learning and foster others’ growth and development to make meaningful change in the world.

Michelle Obama’s story provides us with a narrative that has broader lessons for educational policy and practice: Becoming a successful, happy, and productive individual and community member was the outcome of life experiences that provided support for her development; iteratively challenged her to learn and grow; and continually reinforced that she had value and the potential to achieve great things.

These strong supports for her social emotional growth and the opportunities to be positively challenged spanned her personal behavior and perception, her experiences in educational systems, and her work as an active community member. Educators should take the lessons learned from her life story–from this particular life story–not as an exception to the rule, but as an aspiration for what might be possible for all students.

Family Supports

Michelle Obama began her first formal school experience with confidence and enthusiasm. Her mother had surrounded her during her toddler years with books and trips to the library. From the very beginning, she was given the message that she was smart and capable and that learning held a key to success, interesting experiences, and self-determination. Because Michelle had been exposed to learning and books at home, she was comfortable in the classroom, and that comfort led to a confidence in her abilities that she carried with her throughout her schooling.

Implications for Practice: When families are involved in their children’s learning, students are more successful. This holds true across socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, and gender classifications. Engaging families around learning must be a key piece to a district’s overall strategic plan for student success and learning. This engagement can and should begin, when possible, with early childhood and school-readiness programs so all children can enter Kindergarten feeling ready and capable.

Having an Advocate

When Michelle Obama was in second grade, she was placed in a classroom that was steeped in chaos. The classroom lacked structure, and there was little to no aspiration-based motivation. Michelle was miserable and her learning was stalled. Michelle’s mother intervened and met with the school administration to advocate for change. Soon after, Michelle, along with several other students, was moved into a different classroom–one filled with organization, support, and growth. As Michelle grew older, her mom became a very active member of the school PTA, helping raise funds to purchase equipment and materials to benefit the broader student body. Having an adult advocate ensured that Michelle was in a productive and supportive environment.

The need for support or an advocate can be even more important when one does not feel connected to the educational environment. While in college, Michelle reported feeling disconnected from the dominant culture and was initially uncertain how to be successful within the community. In finding a staff member who was able to help her frame the cultural dynamics at Princeton, and Michelle’s opportunities to successfully navigate the challenges therein, she was able to be successful.

Implications for Practice: There is no questioning that a parent is, and should be, a child’s number one advocate. They are most experienced in the child’s strengths, challenges, and needs. When making plans for students, it is imperative for schools and districts to include families in the conversation. But not all parents have the same experiences and background knowledge to know the variety of support systems they can connect to their students. Parental support needs to be bolstered by encouraging other supportive relationships within the child’s life. This approach of parents plus others ensures layers of support and expertise assisting in healthy human development as a foundation of educational achievement.

Being Challenged through Deeper Learning

Throughout Michelle’s educational career, she was provided with opportunities for deeper engagement and learning. In grades K-8, Michelle had teachers who facilitated learning experiences that encouraged collaboration and conversation, personalized learning plans, and goal-setting. Michelle attended high school at Chicago’s Whitney Young Magnet School, a school geared toward academically high-achieving students from throughout Chicago. The school gave Michelle access to high-level college prep curriculum and reinforced that, with hard work, she was able to rise to the challenge. These opportunities built self-confidence in her academic capabilities and ensured that she was college- and career-ready at the country’s most elite institutions.

Implications for Practice: There are emerging pedagogical practices that provide students with opportunities to engage more deeply with what they are learning, to add value to the learning by understanding its practical implication or purpose, and to promote agency. Innovative practices such as project-based learning, deeper learning, place-based learning, the utilization of a growth mindset, and the inclusion of social and emotional learning allow students to find meaning in their education, promoting greater achievement and college and career readiness.

As Michelle Obama matured into her womanhood as a person and a professional, she took ownership of ensuring that she had a support network around her and of placing herself in environments that challenged her development. And she began to give back to her communities by providing support to others. This maturation manifested in her enabling representative community engagement and in her emerging as both a mentee and a mentor.

Community Engagement

Michelle returned to the Chicagoland area as a degreed professional and became a law associate in a firm focusing on intellectual law. Her interests, expertise, and a desire to make a difference led her to move to the public sector in the Mayor’s Office and then leadership roles in non-profit organizations. Her positive impacts resulted in her being named an Associate Dean for Student Services at the University of Chicago and eventually Vice President for Community and External Affairs at the University of Chicago Medical Center. In these roles, she was able to design systems supporting thousands of students at one of the most prestigious higher education institutions in the world. A hallmark of her work in this opportunity was connecting students and resources from this elite institution with the local community surrounding it. Michelle treated moving to these opportunities as a way to contribute to the employer and to have the employer’s membership contribute to the community physically adjacent, but socioeconomically, very distant.

Breaking down barriers was a characteristic of her personal development that was also a hallmark of her professional life. In creating opportunities for hospital staff to bring their skills into the community, having neighborhood adolescents shadow hospital and university employees, and creating a system of care based on university emergency room visits leading to sustained primary care services, Michelle provided support that highly impacted all involved.

Implications for Practice: Michelle understood the importance of engaging the community and the benefits involved for both the educational and medical institutions and for the overall community. When a community feels connected to a school or institution, all parties are better off. Healthy individual and group relationships are an evolving dynamic of behaviors, expectations, and dialogue. Transactions of resource allocation and events then occur within a larger context of persistent presence and long-term sustainability within a geographic area and across generations. Schools can strengthen and build the core of the community, rather than existing as a siloed public service. Being present in larger community gatherings, and having the neighborhood and its institutions present in schools, shows students that the community is invested in them. This enhances motivation for them to achieve.

Mentee to Mentor

In reading Becoming, it was remarkable–even stunning–to realize that this exceptional woman who has risen to such heights, throughout her life battled the constant refrain “Am I good enough?” What made a key difference in turning an ordinary life into this extraordinary one was that at both critical and seemingly mundane moments throughout this journey, Michelle’s world–her parents, brother, teachers, mentors, and Michelle, herself–answered, “Yes, you are good enough.”

Having that reinforcing message was something that occurred by different voices, from different perspectives, at different stages in Michelle’s development. From family, to teachers, to staff in college, to professional colleagues, Michelle regularly had support from others who encouraged her to take on different and more demanding roles. The message from these mentors was never that some external person or agent would make her or a situation okay. Rather, the message was that she–Michelle–had the skills to take actions that would lead to growth and success. In short, she had value and could excel.

It was this message which Michelle sought to systemically bring to others as a Dean and as First Lady. Through roles at Public Allies, an organization geared toward mentoring young people for work in Public Service, or her relationship supporting the Elizabeth Garrett Anderson school in Britain, a school for girls from mostly underserved populations, there was a measurably positive impact from reinforcing this message for other young people. And she maintained her relationships with her own mentors while emerging as a leading national expert on mentorship herself.

Implications for Practice: Echoing the implications from community engagement, the lessons from Michelle’s story on mentoring take insights on connections and relationships and apply it to the individual. When adults take the time to be present and show the respect of listening, students are affirmed in their value and capacity. And kids will invest more when they feel they are being invested in. Students need to have a few deep and persistent relationships and several less intense, additional layers of connection. Clubs, sports, and other school-based extracurricular activities can provide such mentors and role models. And so can community-based organizations such as Boys & Girls Clubs, YMCAs, employment, municipal activities, and faith based communities. Schools can work to promote both internal and external options and work to intervene with those students who are not connected to any activities. These experiences enable students to both learn from others and to try out different versions of themselves. Learning that they themselves can adjust to multiple circumstances, and that they are in a never-ending process of developing, allows for confidence in both their current identity and the expectation of growth.

All Children Can Become Extraordinary

As Michelle Obama reflected on her amazing life journey in her book, she shared: “I’d been lucky to have parents, teachers, and mentors who’d fed me with a consistent, simple message: You matter.” Having support and being challenged by high expectations both at school and at home catalyzed that message taking hold, giving her the foundation to make personal effort to pursue passions and exercise choices, ultimately achieving extraordinary feats. Michelle’s mission in her public life has been to create educational structures, policies, and programs to show others that they, too, are good enough; that they have value; that they are worth it. This should be a foundational piece for how educational systems are constructed.

Educators can and should ensure that this kind of systemic support and engaging and challenging curricula are available to all students. Positive and productive relationships within the school and with families should be a cornerstone for how educational systems are structured. Educators can take inspiration from Michelle Obama’s life and move to ensure that each child gets the supports and challenges needed to enable their personal effort in Becoming an exceptional person.

For more, see:

- The Importance of Being a Mentor and Having a Mentor

- New Guide Helps Parents Support Students in LEADing in Their Learning

- Families are Fundamental: Takeaways from The National Center for Families Learning Conference

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

Carol Sweet

When was she stripped of her law degree and why? I know she did something illegal but I can’t remember what.