10 Ways to Scale Nonprofit Impact

Nonprofit organizations are formed with a charitable intent around a mission–a big problem or a great opportunity. There are more than 1.5 million nonprofit organizations in the United States. While they will receive more than $400 billion in donations this year, most of that is concentrated in a small percentage that have achieved scaled impact.

There are some good reasons for forming a nonprofit corporation (one that qualifies as a tax-exempt organization under IRS code section 501(c)(3)):

- You are eligible for private and government grants (not typically available to for-profits).

- Unlike a loan, If you receive a grant you don’t have to give the money back.

- Donations are tax deductible for your donors.

- If you make a profit, you don’t need to pay federal corporate income taxes and, in most instances, do not pay state corporate income, franchise, excise, use, and sales tax.

- You may receive generally favorable treatment from educators skeptical of private enterprise.

There are a couple downsides to forming a nonprofit corporation. The first is the loss of control. You need to put together a board of directors that become your boss–and they can fire you. You may be subjected to more scrutiny because your finances are open to public inspection. If your organization grows and becomes profitable you can’t sell it. Nonprofits may pay lower salaries and have less incentive compensation than for-profits that can make it a challenge attracting talent.

The final disadvantage, and the subject of this post, is the challenge of bringing a nonprofit to scale. For nonprofits, scale means more fundraising and more headaches but probably not a lot more remuneration—lots of hard work, more risk, and not a lot more reward.

Despite inherent disadvantages of the nonprofit structure, there are big problems to solve and solutions that should be brought to scale. Based on two decades of work with over 400 nonprofits, following are 10 tips for expanding the impact.

1. Lead users. Identifying your customers/clients and deeply exploring their needs helps you understand the problem you’re trying to solve. Eric Von Hippel at MIT has been studying the sources of innovation for decades. In sector after sector, it comes down “lead users” who have the passion and persistence to keep working a problem until they find a solution. They are the first innovators although those that commercialize their discoveries usually get the credit. Nonprofit expert Dave Lash suggests, “find, protect, and invest in lead users.”

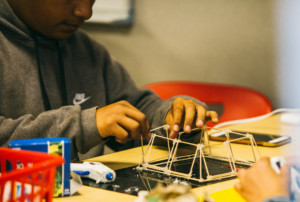

Teacher leader, Moss Pike, suggests using user experience (UE) strategies when it comes to designing learner experience (LX). We recently visited DSISD in Denver where students learn to conduct deep empathy research in support of a design thinking process.

2. Build networks. LinkedIn founder, Reid Hoffman, urges aspiring entrepreneurs to connect to central nodes on the network. Nonprofit leaders should do the same by developing five networks: personal, regional, industry, innovation, and enterprise resources. Social media can make it efficient to build relatively large networks fast; you don’t need to use all of them, pick a few that are important to your customers/clients and make a sustained and focused investment (see Getting Smart on Social Media).

It is important to build connections because most big foundations don’t accept unsolicited proposals so you’ll need to find an opening and introduction.

3. Lead Donors. Now that you’re connected and informed, it’s time to raise some money. Crowdsourcing is a new option but it sure helps to have a lead donor to get things started. Lead donors may include friends and family, a local community foundation, or a national foundation focused on the problem you want to solve.

With a lead donor in place, create a scalable fundraising engine, examples include:

- Creating local funding alliances (e.g., a dozen MIND Research citywide math initiatives rallied support from local foundations and corporate donors);

- Creating a scaling alliance (e.g., Bridgespan raised $10 million from 4 national funders to support a scaling plan);

- Creating a broad donor network (e.g., WorldVision raises $1 billion from thousands of donors);

- Creating a sponsorable advocacy event (e.g., Alliance for Excellence in Education created the annual Digital Learning Day) or

- Highlighting a crisis (e.g., climate change, animal abuse, cybersecurity).

4. Scale ready. Scaled impact requires a program or intervention with a strong theory of change (i.e., a logic model of if/then events that lead from current to desired future state). That requires deep contextual knowledge of relevant public policy, behavioral economics, and technology–and a sense for which trends you can anticipate and leverage (e.g., see 40 education trends).

An external evaluation of the program may validate that a program is scale ready and, if so why, and which program elements can be transferred to a new setting. However, if you’re watching your service delivery data, an external evaluation will probably be more valuable to funders than your team so try to pay for it with a dedicated grant rather than operating cash flow.

5. Window of opportunity. It will help fundraising efforts if you can make the case that you’re working on an important problem and that you’re proposing a timely solution. Be ready to make the case that your solution is the right idea at the right time in the right place.

Timing is more important than ever because most big foundations have adopted “strategic philanthropy” which means they have outlined a detailed change agenda; you’ll need to find yourself in their agenda, use their language and metrics, and hit their grantmaking window.

6. Credibility. Perhaps most important to donors is that you appear credible as an organization—you understand the problem and have the capacity to do what you’ve committed to do (i.e., you get it and can get it done). Reference projects, client case studies, a capable staff, a big network, and initial funding can all help boost credibility.

7. Fee-based. Successful nonprofits often develop a strong base of earned revenue to reduce philanthropic dependence. Charging for some of your services will not only improve your sustainability, but it will also encourage you to keep an eye on your costs.

Examples of sustainable revenue streams include:

- Sell a product (e.g., SAT, ACT, and ETS sell tests)

- Sell an advisory, training, or research service (e.g., New Tech Network provides school startup services; GPS operates contract learning centers); ADD

- Sell sponsored content (e.g. Nellie Mae Education Foundation sponsored Smart Parent: Parenting for Powerful Learning); UPDATE

- Sell a subscription service/membership (e.g., after launch New Tech Network provide platform and support services);

- Sell advertising/sponsorship (e.g., NPR sells corporate and philanthropic sponsors);

- Use a freemium strategy to sell premium services (e.g., NEW

- Create a for-profit subsidiary using any of these strategies (e.g., National Center on Education and the Economy developed America’s Choice which was sold to Pearson).

8. Sweet spot. In many cases, you’ll need to be able to describe a solution that is cool but not too cool. In Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation, James Utterback discusses the gravity of the dominant design (such as the traditional school model) pulling down and crushing “deviant” efforts. But go too far from the dominant design and you risk losing credibility. The sweet spot for innovation is the orbit that balances these forces.

Balancing improvement and innovation is particularly important in education where folks that get out ahead of their community can get fired and where progress takes a sustained push.

9. Adaptive entrepreneurship. Amar Bhide wrote about successful entrepreneurship in The Origin and Evolution of New Businesses. Lash built on Bhide’s work to outline four elements of adaptive enterprising:

- Plussing from one near-term opportunity to the next;

- Leveraging skills and assets in increasingly sophisticated and uncommon ways;

- Upstreaming attention and actions on emerging needs and trends; and

- Spanning disparate ideas and resources assembled through proactive cultivation.

10. Capacity. The last step before a big expansion is building capacity. Make sure you have a plan to develop the people, systems and resources to go to scale. Consider management succession—who could do your job? Who could step up and manage a new location? Make sure your culture is scalable; how will new locations make decisions, treat customers, and value resources?

These ten steps will help you build a thriving nonprofit. Donors and customers/clients may be asking you to expand. It may be time to pick the right scaling strategy.

Scaling Strategy

There are three basic scaling strategies: expand services, expand locations, or advocate for your solution.

1. Service expansion. If you are delivering value to a group of customers/clients it may be time to add new products and services. Focus groups and pilot projects can help you gain quick insights into the potential to create value. Donor discussions will help you understand if you can rely on your existing base or it new donors will need to be cultivated.

2. Replication. Adding new locations for your services can be accomplished by operating new locations yourself (like AAA) or by creating a network of semi-autonomous affiliates (like the KIPP school network) or something in between (like Communities in Schools which has local and regional affiliates that share an operating and measurement framework).

The key to replication is figuring out what should be tight and what should be lost—what will remain common and where will local affiliates have flexibility? The answer depends on your value creation formula and the variability in context variables for each affiliate site.

3. Advocacy. Rather than expanding to new locations, you could just share your success via open resources, success stories and advocating for productive policies. YouthBuild supports over 260 urban and rural local programs through public narrative campaigns and with policy advocacy on Capitol Hill.

Scaling a nonprofit is hard work. It often includes many of the challenges of building a business with less financial rewards. The upside is a chance to change a corner of the world for the better.

For more, see:

- 4 Strategies For Scaling A Successful Program

- Scaling Nonprofits: Lessons from the Experts

- 3 Challenges to Human Development: Potential, Poverty, Productivity

This is an update to a 2016 post.

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

Neville

Brilliant we need a guy like you in South Africa well done

Adrian Jones

I like how you mention that when it comes to starting up a nonprofit organization, one of the most important things to do is to build networks of people you can turn so that when you do get the group off the ground, you have an easy-to-contact group of people who can help you out with the rocky start. At the same time, it's also a good thing to make those connections early since those connections would eventually prove to be useful in the long run and then they would be able to lead more people your way in the future. If I had the chance to start my own non-profit organization I would most definitely build a group of contacts early!