Innovating Large-Scale Assessments: Design Considerations for Education Leaders

By Dr. Stuart Kahl

Interest in innovative assessment practices is growing among education stakeholders today for a variety of reasons. These reasons include the flexibility in accountability assessment offered by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), concerns about time spent on testing at the expense of instruction and general dissatisfaction with the focus of traditional tests on lower-level cognitive skills.

The “next-generation” assessments recently implemented by the assessment consortia PARCC and Smarter Balanced were not so different from some states’ previous assessments. That many schools could administer them online was a good thing, but they really didn’t capture the spirit of “multiple measures,” as was better defined in ESSA than in NCLB.

The consortia assessments were still highly secure, on-demand tests delivered in fixed windows of time near the end of the school year. The performance tasks, albeit of high quality, were typically writing samples in English language arts and thematically related constructed-response questions in mathematics—still secure, on-demand, and of relatively short duration. And overall, testing time was greater than it was before in many states.

Multiple Tests, Less Time on Testing? Not Necessarily

One of the rationales for the use of interim assessments now allowed by ESSA is to shorten testing time by using shorter tests multiple times during the year. This approach does not constitute less intrusion in schools if the tests are just shorter forms of the same type of testing. Schools still have to deal with all the administration requirements—test prep, school schedule disruption, inventory and security of testing materials, testing all students (with accommodations for some) and return of materials—three times during the year instead of just once.

The results of this type of interim testing would have no more immediate instructional use than the end-of-year summative assessments, which are not really designed for that—they are designed for program evaluation and school accountability. Those are worthwhile uses in and of themselves, and we should not expect more of these assessments.

This does not mean that benchmark or other forms of interim assessments cannot be tremendously useful as part of a district’s balanced assessment system. However, with respect to state accountability assessments, we have to be careful about what we ask for.

A Design for Accountability that Saves Time and Reduces Testing Burdens

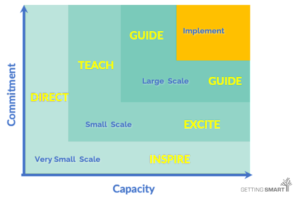

A state can benefit significantly from the ESSA flexibility. The trick is to design a program that utilizes both a shortened end-of-year test and some form of a curriculum-embedded component that tests skills not readily assessed by the end-of-year component—e.g., higher order skills.

Performance tasks that are truly curriculum-embedded, unlike large-scale performance assessments that have been used in the past, should not result in additional burdens on the schools. They can be planned activities within instructional units that teachers would want to use anyway.

Some of the restrictive or time-consuming requirements of accountability tests—such as scheduling, security and professional scoring—can be avoided. Curriculum-embedded performance tasks can be administered whenever the units that contain them are presented, at different times in different schools.

Security need not be a concern as long as the teachers follow the directions for the tasks, just as they follow directions when administering traditional accountability tests. Teachers’ scoring of their own students’ work can provide immediate results and feedback, while a sample score audit and adjustment approach can be employed for accountability purposes.

Teacher scoring and shortened end-of year tests are cost-savers. Combining curriculum-embedded tasks with year-end tests can also yield more reliable and valid results because of better coverage of the higher-order skills called for in college-and-career-readiness standards.

Designers of innovative accountability assessments should keep a few principles in mind:

- Teachers should be able to see some reasonable instructional benefit from at least one component of a program.

- Assessment innovation should not place an additional burden on teachers.

- Transition to an innovative approach should be phased in over time.

We’ve tinkered with performance assessment in state testing programs for years now and have learned our lessons. We know how to do it. We know how to produce high-quality tasks and results with the required comparability across schools. It’s time to take advantage of what we’ve learned and the flexibility allowed us by ESSA.

For more, see:

- It’s Time for a New Assessment System

- Guidelines for Assessment of Place-Based Learning

- Reclaiming Assessment for Deeper Learning

Dr. Stuart Kahl is founding principal of the nonprofit assessment organization Measured Progress. Follow them on Twitter: @MeasuredProgres

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.