Pacing in Competency-Based Learning

In a recent school design workshop, a school leader asked, “How do we avoid students racing through the system at the expense of depth?”

To make this more challenging, she added, “How do we avoid encouraging parents to compete/brag on progress (e.g., my son is 1.5 years ahead of his age group)?”

No drag racing. Learning isn’t a drag race, but we may inadvertently set up rules that suggest otherwise. Most of us have seen well-intentioned credit recovery courses that were nothing more than clicking through online content and assessments. It may help students quickly earn credits, but it rewards low-level engagement and recall.

To avoid racing it’s important to measure what matters: if you want depth, assessments should value it. As NGLC MyWays suggests, it is important to measure creativity, critical thinking, entrepreneurship, collaboration and social skills. As Buck suggests, requiring key success skills, sustained inquiry and a public product contributes to deeper learning. The iNACOL definition recommends:

- Competencies include explicit, measurable, transferable learning objectives that empower students.

- Assessment is meaningful and a positive learning experience for students.

- Learning outcomes emphasize competencies that include application and creation of knowledge, along with the development of important skills and dispositions.

The great “show what you know” school networks (HTH, NTN, EL) have retained an age cohort model and encourage the benefits of peer learning opportunities in a project-based environment. They avoid the free-rider problem by assessing individual work.

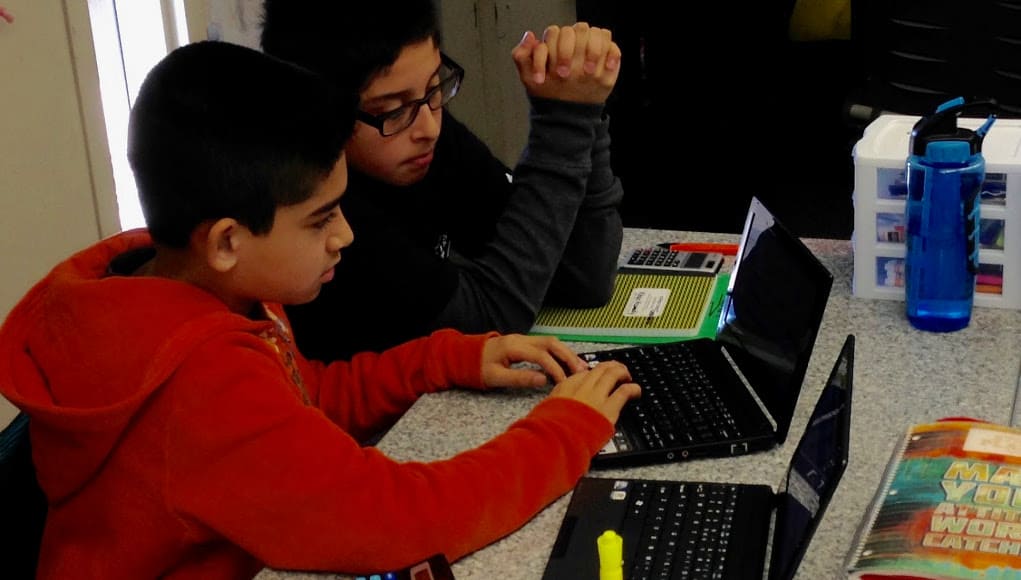

We’ve seen schools that encourage peer learning with cool avatars on learning platforms that signify who can help with what. Other schools encourage collaboration with low-cost hacks (need help/can help).

University Academy superintendent Tony Klein wants to create an environment that keeps his top students on campus (and avoids racing to complete or leaving for a school with broader options) by offering competitive athletics and electives.

In a 15 part series on implementing competency-based policies, Chris Sturgis offers this advice:

“Guard against language of students being ‘fast learners.’ It is a red flag for two different reasons. First, it is possible that students are not being offered enough opportunities for deeper learning, which generally takes more time. They may be fast only because the level of knowledge is closer to recall and comprehension than it is to knowledge utilization. Second, the term ‘fast learner’ implies a fixed mindset—you are or you aren’t. To keep your culture of learning robust, focus on effort rather than comparison.”

Prodding laggards. What about the opposite problem of students that are lagging behind? Effective performance monitoring can help. A learning platform that suggests adequate pacing can provide daily visual reminders of work to be done by class and task.

Sometimes public performance monitoring can help. The teacher below at Henry Ford High School in Detroit is tracking the performance of project teams on the whiteboard, creating a little positive social pressure to maintain progress.

In a six-part series, we examined the positive and negative aspects of public performance monitoring. We drew six conclusions: measure what matters, be timely and relevant, honor different motivational profiles, encourage effort, blend competition and cooperation, and (perhaps most important) avoid shame. Public shaming can be very damaging—especially when the problem is some form of trauma rather than sloth.

More from Sturgis here:

“The term pacing is sometimes used to talk about the planning and supports needed to help students make progress. When learning is a constant and time is a variable, more instructional supports and more time on the part of the student and teachers will be needed when students are not “keeping pace.” If pacing is not adequate, schools need to engage students and their families, seek out additional resources, or plan for more time for the students to make adequate progress. If there is an issue at play that is preventing the student from advancing at an adequate pace, then individual plans can be created.”

Making Community Connections Charter School‘s Kim Carter explains, “One of the most significant distinct aspects of a personalized competency-based system is the ability to adjust pacing to meet every learner’s needs. This shouldn’t be construed to mean that each learner gets to set his or her own pace. At MC² we rely on ‘negotiated pacing with gradual release.’ This is an integral aspect of developing student agency and the central role of managing motivation in an educational system designed to create proficiency not just in facts and skills, but in habits and dispositions to be critical thinkers and lifelong learners.”

Slow pacing could be a problem of skill, will, negative peer pressure, or trauma-induced stress. The only way to know is regular communication within a supportive culture. It could be a path problem not a pacing problem—the work could be really boring and seem irrelevant to the student. Expression of a growth mindset can be highly context-specific.

It’s Goldylocks pacing we’re after—just right on every dimension for every student. A competency-based environment should allow students to progress in each area of student learning at a pace that’s just right through a mixture of individual and group work.

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.