Reinventing A Secondary Program From The Ground Up

Melissa Strong

Think of the biggest experiment or riskiest idea you’ve tried in your teaching this year. What did you stand to gain if it went well? What did you stand to lose if it didn’t?

At Harvard-Westlake School in Los Angeles, California, we embarked on a significant pedagogical “experiment” in our Spanish program starting this year, which is still underway. It would not be overstating things to say that we are truly reinventing our program from the ground up. We already had a well-established program that we had built and polished as a team over the years. We had excellent students who scored well on Spanish AP exams and who were graduating from our school to attend highly respected colleges and universities. And, though we ourselves had identified areas where we could improve, we were not being asked by our administration, our students or their parents to fix what didn’t seem to be broken. So why did we voluntarily decide to take on this project? And, more importantly, was it worth it?

For those educators who may be pondering the questions, “What if I were to teach this concept, this unit, or this subject completely differently?,” or leaders and administrators who may be asking, “How can I support our programs in implementing change?” I wanted to share our experience: why and how we decided to reinvent our program.

Where do we want to go?

Before we embarked on this project, we dreamt that our classrooms would be full of students enthusiastically engaged in creating, interpreting, and speaking in the target language, something like this:

However, in reality, we knew that our classrooms too often looked like this:

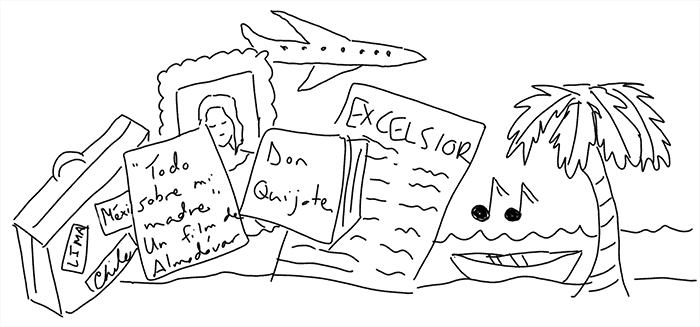

We also wanted to instill in our students a love for this:

…and, when our students leave our classes, we hoped they would successfully navigate situations like these:

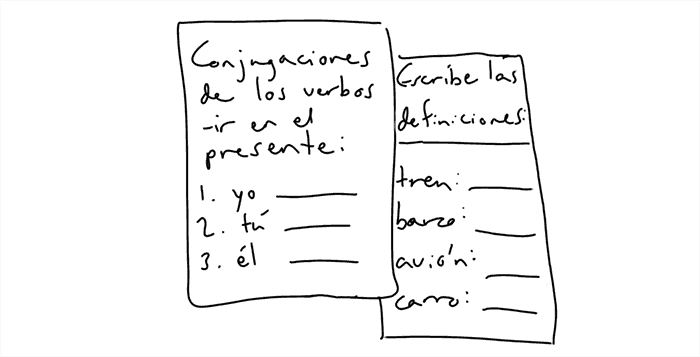

However, we realized that we often spent too much of our class time on “processes” like this:

…while our students focused too much on “products” like this:

We knew that we needed to do something differently, because what we were currently doing didn’t always promote in our students the skills and values that had inspired us to become language teachers in the first place.

Navigating the trip

We had several goals for our Spanish program:

- ACTFL (the American Council for the Teaching of Foreign Languages) provided clear standards with regard to what defined excellence in language instruction, including the use of integrated performance assessments (real world-based tasks set in cultural context) as well as standards for determining linguistic proficiency in our language learners.

- Part of the cultural awareness any language course should promote, and implicit in our new school mission statement, was to inspire informed and engaged global citizens.

- As educators, we also had the responsibility to produce future-ready learners and educated digital citizens, a need ever more present as our school was about to expand its 1:1 student laptop program from 7th grade-only to our entire middle school campus (grades 7-9). ISTE (the International Society for Technology in Education) provided us with a great set of standards for teaching digital literacy.

With our planned adoption of a new textbook series and associated online peripherals in all of our level one through three Spanish classes, we had found an opportune time to reinvent our program. What remained was simple: to create our new Spanish program. Piece of cake…er, flan.

Are we there yet? Are we there yet?

The first two steps, as profound as they were, were just the packing in advance of our travels. The hard work began with the curriculum reinvention that continues today:

- We formed collaborative teams of Spanish teachers across our middle and upper school campuses, shared the load in planning units, and redistributed whenever necessary. As chair of the Middle School World Languages Department, I volunteered to work on the level 1 and 2 teams in adopting this new approach over the coming year; my counterpart, the chair of the Upper School World Languages Department, volunteered to work on the level 3 and 3 Honors teams in implementing this approach. She and I recognized that our department did not have a tradition of working closely together across our geographically separate campuses to collaboratively plan courses, so we reached out to each other and to our colleagues to encourage them to do so, making use of technology (such as Google Drive shared documents and folders) to aid us in bridging the distance as we planned shared lessons and materials, as well to aid us in making our curriculum more transparent and coherent across levels.

- We sought help, guidelines, examples and mentors. (We owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to Laura Terrill, who provided a workshop on theme-based curriculum planning and integrated performance assessments to our department.)

- We invented real-world based tasks, researched the news and online media for current events, cultural topics and materials, networked with other teachers via Pinterest, Twitter, etc., and borrowed or adapted great ideas shared with us or stumbled across. My colleagues have not ceased to amaze me in their creativity and collegiality in developing countless unique and engaging lessons for use by our teams.

- We experimented, evaluated the results, revised and repeated, remembering that failure was just the elimination of one more approach that would not work. (Thank you, Thomas Edison, for a highly apropos paraphrase!)

- Lastly, and most importantly, we supported and encouraged each other through success and frustration as we learned new pedagogical strategies together.

As a result of this teamwork, I’m excited to see students in our courses regularly tackling real world-based tasks, such as:

- Read authentic articles, listen to pop music and watch videos intended for a native-speaker audience, which they then analyze for cultural content and relevance to issues of personal and global significance;

- Create Piktochart infographics to educate others on topics of personal, social and cultural significance;

- Film mock commercials to sell a technological innovation, which they then share with the class via Google Drive and YouTube;

- Create presentations to introduce their “real” and extended family members to classmates using Prezi and ThingLink;

- Build Blogger online language portfolios for personal reflections on current conversation topics, as well as to document and share their projects and progress.

Reflecting on our trip: Was it worth it?

The final question to ask is how do our teachers and students feel about our new program? As we have not yet completed the first year of our new approach, it is still early to make a “conclusive” evaluation of the relative strengths of our former and current programs. Our initial impressions may be best demonstrated via illustration.

On some days, students and teachers feel like this:

For example, we are proud of the increased enthusiasm and boldness with which our students dive into improvisational oral activities, given our greater emphasis on use of the spoken language to address meaningful tasks. Our students have expressed enjoyment of more creative projects and “realistic” activities.

On other days, however, our feeling is a bit more like this:

Some days, we just don’t feel like the “experts” we like to be as teachers. We are experimenting with new activities and tools, and are often learning along with our students. And because our activities are so different from the quizzes and tests to which many of our students are accustomed, they sometimes feel less secure as they are learning to prepare for assessments that require more than memorization of content (vocabulary, verb conjugations, etc.), but also the ability to creatively and appropriately apply it in completing a contextualized task.

Some days, we just don’t feel like the “experts” we like to be as teachers. We are experimenting with new activities and tools, and are often learning along with our students. And because our activities are so different from the quizzes and tests to which many of our students are accustomed, they sometimes feel less secure as they are learning to prepare for assessments that require more than memorization of content (vocabulary, verb conjugations, etc.), but also the ability to creatively and appropriately apply it in completing a contextualized task.

Our students and our faculty have learned a lot…and we have also had some stumbles this year. That said, do I feel it was worth it? Absolutely. As a result of this project, students and teachers alike have gained the confidence and skills to handle new situations in different cultural contexts with flexibility and creativity. We are all better at what we do for having stretched ourselves this year and, knowing what we and our students are capable of, I expect us to continue to challenge ourselves to make our program ever more effective and meaningful for our students.

Even still, the decision to embark on a project like this–and to stick with it as we encounter obstacles–is not made easily. The risk, of course, is always “failure.” This is where it is up to administrators, including department chairs, to “walk the walk” and be willing to take those same risks we ask of our programs. If we ask teachers to “implement more technology,” are we doing so ourselves, and can we convey to curricular teams why we believe it is essential? If we believe that our students should be more engaged, are we developing ways to accomplish this in our own courses and sharing those ideas with our colleagues? And if we find that we, ourselves, are stuck, are we humble enough to seek mentoring and to work to build those new skills in order to improve our own practice? If we mean to effect pedagogical and cultural change in our schools, we have to be.

In the context of the classroom, what does “failure” really mean? This approach did not work, so I will have to try presenting this idea, asking this question or teaching this skill another way. Failure sounds quite a bit like the learning we hope our students will engage in everyday.

For more, check out:

- Elevate and Empower: World Language Instructors as Key Players in the Shift to Competency-Based, Blended Learning

- Infographic: Next-Gen World Language Learning

Melissa Strong is Chair, Middle School World Languages Department en Harvard-Westlake School. Follow Melissa on Twitter with @DeLibrosCorazon.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.