Catching Up! | Exploring Learning Spaces, AI Readiness, and Global Education Innovations

Key Points

-

AI can equalize individual productivity to that of a team and enhance team outputs, especially in cross-discipline projects.

-

New Zealand’s competency-based education and microcredentialing system offer a model worth exploring for U.S. states.

In this episode of “Catching Up!”, join Mason Pashia and Nate McClennen as they explore the intersection of learning spaces, AI readiness, and global education innovations. Discover how AI-assisted teams outperform conventional groups and what New Zealand’s competency-based education system can teach us about learner records. Dive into the role of technology adoption inspired by the Amish and how this shapes community values. Whether you’re an educator, policymaker, or lifelong learner, this episode offers insights into the evolving landscape of education and the future of learning ecosystems.

Outline

- (00:00) Introduction and Overview

- (03:30) Travel Insights and Education Systems

- (07:17) Parent-School Communication and Student Proficiency

- (09:52) Fan Mail and Demand for Innovative Education

- (21:33) The Pendulum of Knowledge and Competency

- (23:50) New Zealand’s Competency-Based Education System

- (27:09) Global Lifelong Learning Initiatives

- (33:59) AI in the Workplace: A Study on Efficiency and Emotions

- (37:10) Human Connection in the Age of AI

Introduction and Overview

Mason Pashia: Hey, Nate. It’s time to catch up.

Nate McClennen: Hey Mason, it’s that time again. Welcome, everybody. Welcome, listeners. Excited to catch up with you today.

Mason Pashia: Likewise. Today we’re covering a ton of really interesting and semi-related themes. What are you gonna be talking about?

Nate McClennen: All our themes sort of connect together. But today we’re thinking a lot about the demand side of learning innovation. We’re thinking about learning spaces and alternative learning spaces and what that looks like in communities. We do a little riff on microcredentialing in New Zealand ’cause it’s good for us to travel abroad.

And then we do a little bit of thinking about AI-assisted teams, continuing on our talk about AI agents from last time and some interesting research that just came up. So, what else do you wanna add?

Mason Pashia: Yeah. We also talk about how to audit if your place is ready for AI-assisted teams and other AI tools, as well as returns on innovative investments. We also asked some questions about whether abundance is possible without a lifelong learning infrastructure. And as technology adopters, what can we and our school systems learn from the Amish?

Nate McClennen: Awesome.

Mason Pashia: Gonna be a great conversation.

Nate McClennen: What do you see this week?

Mason Pashia: I’ve been at a lot of conferences this week, so I’ve seen a number of things. Something that struck me this week is that we kind of need a new term for missing information rather than misinformation. I think they both exist and they’re both problems.

For example, I was in a room at the CoSN conference in Seattle, and we were talking about FERPA. The person was doing a presentation and was like, let’s do a quiz on FERPA. Everybody in this room must know FERPA pretty well ’cause they’re like the district liaison for FERPA. And we got two out of five right as a collective in the room. And everybody was very confident in their answers. So there’s this weird thing where there are a bunch of gaps, I guess. And as we go into this AI world, I think everything’s gonna get accused of misinformation, but there’s actually this other spot where people just make a hunch off of something that they have and then it eventually just cements. I think that can be a cause of misinformation, like a few degrees out, but internally, I think it’s just missing information.

Nate McClennen: We’re doing a presentation at the air show in San Diego this weekend on Sunday, and it’s about media literacy and doing it with Read over Ed3DAO. So this will be in the past for those who are listening, but the concept is about media literacy in the age of AI. It does make me think that we’re talking a lot about misinformation and disinformation.

But almost it’s the abundance of information going on your theme from last time. This abundance of information causes us to only have a few puzzle pieces in the puzzle at any one time. It’s almost impossible to keep up no matter who you are in whatever profession because of the volume that’s coming through. So I like that we have a third piece here, or a second piece that’s parallel to misinformation. It’s not all devious. Some of it is just you can’t keep up and understand everything.

Mason Pashia: Totally. Totally. Yeah. So, that was something that was up with my week. You had a very different last two weeks; you had some time away and now you’re back. So what have you been seeing or doing with your time?

Nate McClennen: Yeah. You know, it was interesting.

Travel Insights and Education Systems

Nate McClennen: So I was traveling, I was down in Central America for a quick trip through Guatemala and Belize. I’m always interested in education systems. I learned that in Guatemala, the language is obviously Spanish, and then Mayan is taught in a number of schools, especially in the northern and eastern parts where we were. Over in Belize, the language taught is English because it was, at least for some period of time, an English colony in an English-controlled country. But then they have a variety of languages—Spanish, more Mayan, and various dialects of that, as well as more coastal languages and dialects.

I was just thinking about schools and languages over the last week as I was traveling. One of the things that struck me this week is we’ve been talking a lot about learning spaces. We have an out-of-school time town hall coming up. A couple of things came across my feed and emails about spaces where we’re experimenting with learning.

Of course, we’ve been talking a lot about microschools and other options for learning. We’ve always had science centers, performing centers, and art centers, things like that, that are out of school. But there are some interesting things that came across. One was the Wichita Learning Lab in Kansas. It’s a coworking space for education, so people can come with their homeschool or their microschool and co-locate in a space specifically designed for education. I hadn’t quite seen that concept yet, and that might help some of these private microschools, especially those that struggle with facilities.

But more importantly for me, it made me think about whether public systems can have co-located or co-education spaces like this where multiple schools come together to do single things that are still part of the public sector. This connected me to a blog we had on Fab Newport that came across Getting Smart this week. Fab Newport is a great organization in Newport, Rhode Island, that’s a community learning center. Certainly listeners should read about it, but it’s about how to increase STEM and internships. They are doing a lot of the things that might happen in a public school but in partnership with a public school and mentors in the community. That led me to another blog we had in Getting Smart, which was “A School Without Walls” in New York City. Again, it’s playing with this idea of what the space of learning is. This isn’t new, but it’s fun to see these newer iterations start to emerge.

These newer iterations then combine with what it means to get real-world experience, what it means for work-based learning, etc. I’ve been thinking a lot about learning spaces these last couple of weeks.

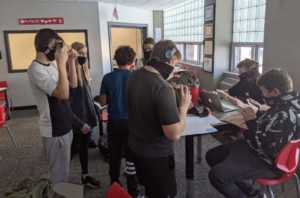

Mason Pashia: That definitely resonates with me, growing up with a dad in K-12 architecture. I definitely thought a lot about learning spaces too. I did a session yesterday at the ACTE conference with Adam Kulaas from Tacoma. Tacoma has some of these really cool city-as-classroom learning spaces between SAMI and SOTA and IDEA, and all these campuses are sort of embedded within the city itself. Students go over there in a way that feels different. The sidewalk is your hallway rather than a hallway. Definitely a great topic for right now, as we’re thinking about these expansive education themes.

Nate McClennen: Right. I love the situation where one of the schools was co-located at the zoo, right? They’re right on the shore, the coast right there. So they have an underwater robotics program that is working on real-world problems. Some of their students are doing internships to do some of the facilitation at the zoo and to take younger students around from the local public schools. This is a public school, and it’s co-located in a zoo. These are really creative solutions to learning spaces that I think at Getting Smart we appreciate and wish there were probably more of in communities.

A couple of things that jumped out at me this week are just… I know Bib Hubbard over at Learning Heroes, and Learning Heroes actually does a lot of surveys and data work.

Parent-School Communication and Student Proficiency

Nate McClennen: But there was something that came across my feed that reminded me of a survey they did with Gallup around—and it was connected to NAEP scores. NAEP scores just came out, and everyone’s wringing their hands and asking, “Well, what do we do?” We haven’t made much change, and we have the COVID drop. But even before that, things were just not… A lot of students are demonstrating proficiency. We talked last time about maybe they’re not performing their best on the assessment. Maybe there are different ways to do assessment. But regardless, the data point here in the survey was around when they survey parents, 90% of parents believe that their child is on grade level, and that’s pretty profound. So 90% believe their kids are on grade level, but when you look at assessments, only about 30% are showing proficiency.

So there’s this disconnect in communication, and I’m not sure it’s… I’m not going to put blame anywhere. I just think this idea of transparency and authentic conversations and how we all work in the student’s best interest… How do we take multiple data sources and put them together? It was just something interesting that sparked in my brain.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, that’s stark. It brings me back to what I was saying earlier about the misinformation versus missing information piece. Right? How much of this is actually a delayed delivery of data, and how much of this is just truly sort of this best intentions assumption about something given your own daily interfaces with your kid? I think that could be a constructed belief off of something that’s less sinister than a system not working fast enough or something like that. Even though we definitely need that, we should be advocating for fast delivery of data and authentic or accurate delivery as well.

Nate McClennen: Yeah, and it goes back to what we advocate for and what a lot of our organizations in our sort of sphere of innovation advocate for, this idea of how can we be better at telling the story of student proficiency? The Carnegie system with letter grades and courses just doesn’t work. In this case, even with that, it’s still not working. So there’s a disconnect, and I think the conclusion of the Learning Heroes Gallup was really about parent and school interface and what that looks like. We’re getting all this churn and conversation about parents’ rights and all that kind of stuff. But really, what I think we need to focus on is not about anybody’s rights; it’s about the partnership, that we’re all in this together to help our children or the students we teach learn. I’m not sure we set up that system well; it can be more adversarial than it can be a partnership. So things to think about.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, absolutely.

Nate McClennen: Hey, I have one more thing, just because we got that…

Mason Pashia: Fan mail.

Nate McClennen: Fan mail. We loved it. It was our first fan mail, so we should celebrate. It was based on the episode, our last, our first released episode a couple of weeks ago.

Fan Mail and Demand for Innovative Education

Nate McClennen: It was in reaction to this idea of how you assess at the learning experience level rather than at the course level, right? Really granular and specific. We gave some examples, and this particular school leader said, “Well, great. We have all the systems set up for that,” meaning the policy allowed for it, the school allowed for it. A student can do an out-of-school experience, and that could be given credit in some way. We sort of asked the question about demand, and she said, “Well, not many students are taking advantage of it yet. That’s our next big goal: how do we make that happen? We want to see examples of that actually manifesting itself.” It did make me think a lot. You talk a lot about the demand and supply side, and it is interesting to think that even when we supply it, which we work with a lot of schools at Getting Smart, that we’re helping them create the supply, you have to think about that demand side. I don’t know how you reacted to that conversation, but it struck me as something really important.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, I think starting younger with those helps because I think a lot of times by high school students have just kind of gotten into this mode of, “I’m gonna just get through school and not really do too many of these extras.” Or they’re like, “I don’t know if I actually have autonomy when I try to make a decision.” So it’s like, how can we create these environments or these cultures of schools where students really feel like they’re given space to run, their passions are recognized as relevant to both them and the school community? Similar to how your first thing was that the Learning Heroes survey was about this interfacing between schools and parents, this one to me was like that interface between schools and students. It’s how are you communicating these options and creating a culture that actually makes them authentically believe that they can have a valuable experience out of them rather than just adding something on.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. My own lived experience, my own two children went to a very innovative school, sort of pre-K through eight, and then moved to a more traditional model after that. My observation is that the demand side is really interesting. They adapted very quickly to a model that was much more Carnegie-based and grade-oriented, even though they were in a place that was very learner-centered before. So I also wonder if value needs to be created externally. So it might be about how do we document learning experiences, and those have value in applying for jobs or getting into higher ed. I’m wondering about internally motivated… you’re talking about internally motivated value, but I also wonder how much external value we need to start thinking about. How can we push local communities, regional organizations to say there is a value for getting data like this and doing experiences like this, and there’d be an advantage for you to do that.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, I mean, not to keep going on this point for too long, but this just brought something to mind. Probably five months ago, the YouTuber Mr. Beast put out his manifesto. It’s a really interesting document on how one of the most successful Gen Z business owners does it. He has this really interesting piece in there where he says, “We’re not trying to make any of the best videos. We are exclusively trying to make the best YouTube video.” Then it goes on to talk about all of the outcomes of a YouTube video. It’s like they need to get to second 31 rather than second 30 on this video. So we need to do everything we can to get them up that one second. I like this external value validation thing. It’s like if the school system you’re in has outputs that are different, like if they’re more Carnegie unit-based, it’s gonna be really hard to convince somebody to work toward a different set of outcomes, which is maybe like value or growth. So, how can you be transparent about your outcomes and make those outcomes innovative to match this experience that you’re providing? The leader that sent us stuff, I think they’re well on their way to doing that. It sounds like they’re doing a lot of this outcomes revision work, which is great. But I do think that had to be done probably in parallel or that it has to be the foundation that’s set to really make a demand side grow.

Nate McClennen: Right, and fundamentally what I want to see is every young person in the U.S. saying “I want something different” or values something that is more relevant to them. Rather than “not relevant to me” and something that has purpose to help them succeed in life. That’s not to say I want to put a caveat out there, for anyone who’s sort of naysaying this and pushing back, there are things we have to learn that we may not like. I don’t think everything has to be learner-centered. I don’t think you should only study the things you like because there are things out there that you may not like at first but are really important. So I have my balance as well, but I do think we need to keep thinking about value in this conversation.

Mason Pashia: And most innovation happens at the intersection of two things. Usually one thing that you really like and one thing that you’re trying to interpret through the lens of the thing that you really like. So if you get rid of that other one, you may have less innovation.

Nate McClennen: And the most innovative people often think way outside their discipline. There was something I was listening to on a podcast the other day where really brilliant, innovative people always had hobbies that were musical or artistic in some way or some other thing they were doing that was separate from what their research or innovation was but somehow freed up brain space in interesting ways.

Mason Pashia: Yeah. I think Stephen King says that about writing. Writers should never major in English. They should major in something else and apply English to it. So that’s great. Let’s move on to the news kind of section.

Nate McClennen: Let’s do it.

Mason Pashia: I kind of have a theme that stitches a few different things together. This is sort of a rapid resource lightning round. I’ll let the audience dig in and really derive more value for themselves from it. But I saw a few things this week that really touch on this idea of readiness and return on investment at a time where we are seeing R&D and lots of things struggling to get funding. So I was like, these are really important. I’m gonna talk about them. Think about them. One was from the org ExcelinEd, and it was about their Pathways ROI analysis. We’ve been talking about pathways for years and really thinking about what takes a pathway from a pathway to, in our terms, a new pathway, right? Something that’s really imbuing value into the experience. They had a pretty simple but useful framework for evaluating some of this. I’d highly recommend digging in there and seeing a few other states that have actually implemented some of these ROI analysis programs at a state level so they can evaluate if their CTE primarily is effective. The idea is that you go through and check out what CTE programs you’re offering, see how they align to K-12 and postsecondary programs, see how they align to high-satisfaction, high-wages, and high-growth occupations—they’re calling this H3. To us, that means something different. But how are your CTE programs aligning to workforce needs, especially in your community? And do all of them include opportunities for college credit, work-based learning, and industry credentials? I think that, like we advocate for this thing that’s even bigger than this, it’s about including other experiences. It’s including other places to build skills. But I think that’s a pretty useful iterative framework to just keep doing every year where you’re like, are we offering enough of these that every kid can access them? Are they all connected to high-value occupations? And is a student that’s in this pathway going to be able to get all of these different things that are kind of more proven to generate success?

Nate McClennen: Yeah, no. Interesting. I think that’s right on. I think those types of questions are critical. I feel that across the country, every public school has to have some sort of CTE type program at the high school. So they’re there, and often they are just a, you complete two courses in a single sector, and you have stamped that you’re a CTE, sort of, you’ve completed a CTE pathway. I think this is just indicating, it’s like, how do we do more than that? How do we push, and it’s much easier just to offer two courses than it is to offer two courses and make sure there’s an IRC or there’s a college credit associated or a real work-based learning real-world experience associated with it. So how do we up the ante? And that goes back to maybe the demand side of the equation is making sure students are saying, “Hey, I want experience.” Two courses are great if I can take two courses in whatever sector I’m interested in, but I need to go do an internship or an apprenticeship, and how can you as a school help facilitate that and give me credit for it. So right on. What’s your next?

Mason Pashia: Totally. The next one when I was at CoSN, they were talking about this guide that I must have just missed called the Gen AI Maturity Guide. It’s a really good resource for doing internal audits of your organization to see basically if you’re ready and in what places you’re ready to adopt AI better into your workflow and as something to grapple with. They broke it into seven sections: executive leadership readiness, ops readiness, data readiness, technical readiness, security readiness, legal risk readiness, and academic AI literacy readiness. I think it was just a really useful tool to a lot of people in the room for being able to see themselves in it, plot themselves at varying points. Nobody’s finger-wagging at you while you’re doing it, but it’s just a really good place to say, “Hey, we’ve made some steps in AI, but we know there’s gonna be some room for growth. Let’s see where we can grow.” As districts are grappling with this, I highly recommend going to CoSN.org/ai. You can find it there, and it’s a really useful tool.

Nate McClennen: Does it have a progression, or is it a yes-no for each one of these?

Mason Pashia: Progression for each one. Yep.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. Love it.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, super helpful. And then the last one is just this ongoing conversation that everyone at Getting Smart is having, but you and I as well, on knowledge and durable skills. I saw a recent report from America Succeeds come out that studied a couple of great schools: Gibson Ek, CAPS, Monet Building 21, and Bostonian Global. They’re really doing the work of evaluating valuable experiences and then saying what is it that made these valuable. I think they are a little bit on the side of, “Hey, we’re not gonna just assume that these things are valuable experiences. We want to know from the learners through tons of research and interviews what actually made them valuable.” Even if it’s just getting us back to our place of assumption, right? So they’ve gone through these first four schools, done their first round of interviews or a handful of interviews at each school, and they’ve derived that interest-driven learning, project-based learning, real-world engagement, competency-based learning and assessment, and intentional advising practices are really the five things that set out an experience. I think four of those would’ve been on my list. And then advising, I think if I would’ve thought long enough, I would’ve come up with, but I was really glad to see that was on there. I think that’s an often-overlooked part of a valuable experience, the advisor role. So I was really glad that showed up. But great report. We’ll link in the show notes.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. You know, Mason, it was interesting reading that report. So really respect what America Succeeds is doing, and Tim Taylor and his team are awesome. I love their process of taking a lot of job descriptions, and that’s how they built their set of competencies. So, great work there, and the report’s great. One of the things I noted was that the report is starting from the place of competency and their portrait, whatever—they don’t call it a portrait, but their competency work—and then they’re saying what are the best ways to teach that. It comes out as interest-driven learning, project-based learning, etc. So the part of that research that was interesting is they’re saying, “Hey, we’ve got these things we want to teach that we think are showing up in job descriptions and are valuable. The best way to teach them is interest-driven learning, project-based learning, real-world engagement.” So I think that’s important. I appreciate their research that’s just reaffirming that we know there are gaps in these competencies in young people and those that are already professionals, and here are the types of learning experiences that will help develop them. It verifies what we’ve been thinking about, and I appreciate the advising piece as well because it helps guide people into what they might do to develop these particular areas.

Mason Pashia: Totally. It makes younger me very happy because back in the day everybody was like, “Oh, you’re creative. I’m sure Google will just hire you,” ’cause Google was the first to kind of raise the arm. It was like, “We want creative people.” So now they’re looking at these skills and they’re like, “How can we make these a little bit more something we actually teach people and measure?” because otherwise, it’s pretty hard to just prove you’re a creative person.

The Pendulum of Knowledge and Competency

Nate McClennen: The other thing I would I’m curious about here, and we’ve had a little bit of a conversation, but I’m having a… it’s not a midlife crisis. It’s just a revelation of the pendulums, the pendulum…

Mason Pashia: It’s okay.

Nate McClennen: Yeah, it’s okay. It’s a mid-older life crisis maybe because I’m already in my mid-fifties. But this idea of pendulum swinging, and I’m noticing now there’s this huge push for competencies and portraits of graduates and these things that we know are really important. I want to make sure that they’re not grounded in emptiness. So this idea of remembering that knowledge is also important, it’s really hard to do interest-driven learning if there’s no knowledge that you can actually drive through, or project-based learning can be described as Swiss cheese projects. They’re really engaging. I love it. I’m doing this incredible stuff. But you don’t actually learn anything because there’s no accountability for the knowledge side of the equation. So fundamentally, we have to know something to be able to do well in these projects and to be able to demonstrate these competencies that are showing up in portraits of graduates. What do you think? Does that make sense?

Mason Pashia: I totally agree with everything you just said, except for the fact that you might be past your midlife crisis. If anyone is going to live to 110, it is Nate McClennan. You remind me very much of Rob Lowe in Parks and Rec when he’s like, “Scientists say that the first man who lives to 120 is already born. I believe I’m that person.” So everything else, full agreement.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. All right. All right. All right. Let’s… I’ve got another one for you, looking abroad a little bit. We’ve been diving so much into microcredentials, and you and I have been thinking about… we’ve been diving into metadata and trying to understand standards, and neither you nor I are technical. We’re not working on the backend. We’re on the front end, trying to understand and talk to our audiences about what’s happening in education. Then we work with programs in schools that are trying to make a difference and trying to redesign and design interesting learning models. But we do desperately try to understand, and you and I Slack often about, “Hey, what do you think about this? What do you think about this?” We’ve been talking about metadata associated with… if we wanted to credential experiences for young people in high school, what kind of metadata would have to be associated with it? So all these really nuanced technical things. So I got caught up in some sort of web search and…

New Zealand’s Competency-Based Education System

Nate McClennen: Stumbled on New Zealand, which it’s always good to look outside the United States and see what’s going on. It is really interesting what they’ve done there. Two things. They have, like many countries in the world that are not state-oriented like the United States, a nationally controlled system. So that, number one, is an opportunity that the United States will never have. We’re always going to be a 50-state type situation, which makes it more challenging in all sorts of ways. But this idea that they have a New Zealand Qualifications Authority, which is their documentation of all things that a student has learned. Think about the work we’ve done on learning and employment records. They have something called the New Zealand Record of Achievement that documents everything from at least ninth grade or high school all the way through tertiary or postsecondary into your adult upskilling life.

So that system is… it’s a common transcript system that starts in secondary school. When you look at a transcript, the transcript is a competency-based transcript. I think about the number of schools we’ve worked with in the United States that are like, “Hey, we should do a competency-based transcript.” But there are not a whole lot of examples in the United States of schools doing this. Then you go to New Zealand, and everything is a competency-based transcript. If you click on the link that I shared, we’ll put it in the show notes, it says “Science” and it has here the competencies, and you have a grade on each one of the competencies or some sort of proficiency on each one of those competencies. It truly describes the skills. Even more, they have a microcredentialing system that’s connected to careers, that is standardized across all industries and the entire country, and those also show up on the New Zealand Record of Achievement. As states, because states are gonna have more and more authority as the federal government, at least in the short term, is gonna shrink in its influence, states ought to look at some of these other countries that have done it. New Zealand is not a very big country. It could be easily, that system could be matched in any one of the states in the United States. So it’s just interesting and a reminder for us to look broader than the United States.

Mason Pashia: Totally. Super, super good point. I think you and I were sparring on this idea a little bit earlier this week, but if you click into it, what you were saying about the microcredentialing for hiring, like it is a credential that will extend for your whole life. So they really have this… it doesn’t feel like it’s quite an LER yet, but it does feel like it’s a proficiency at certain things. It gets up to level 10, I believe, and you can go like 1, 2, 3, and I think they said three is roughly where secondary ends. So everything above three is just building expertise. It’s building this knowledge piece that’s so important to supplement these durable skills. Just a really articulate example of how we can better showcase what we know and are able to do.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. Yeah. And it’s not… I mean, learning and employment record, I mean, anything is a learning and employment record, right? Like a transcript right now could be a learning and employment record, but they don’t have a… I think what you’re saying is they don’t have a true digital wallet set up right now. It’s not self-sovereign, it’s not set up in that way, the things we’ve been talking about. Because you still have to go into the New Zealand Qualifications Authority and request access and request to send, etc. Still centralized control. But I could see the pivot of moving to an LER and a digital wallet and self-sovereignty and things like that.

Mason Pashia: All right.

Global Lifelong Learning Initiatives

Mason Pashia: So hear me out while we’re still lightly global. Last week after, actually after our last catching up, I was asked to come talk to a small group of folks about abundance. We were chatting about it, and I’m still kind of working on the pitch, I guess, of how this really connects education. I don’t think a lot of people are using that language, so it was a great experience. Naturally, like we kind of gestured at this the last time we talked about it, but people were sort of taking umbrage with the ESA approach. They were worried about taking a little bit too much money out of the pool. On the podcast, you had mentioned the Florida school that we learned about from Michael Horn’s show that has begun bundling these or I guess unbundling these a la carte experiences back to students who have taken ESA dollars. So a homeschool student could take a class from the high school or something like that or use facilities.

When I was doing this talk, the thing that came to me was all of these lifelong learning initiatives that I’ve seen around the world where I’m like, really an abundance framework fundamentally is schools changing who they serve and suddenly they’re serving the entire community, not just freshmen through 12th grade at a high school or whatever. Just a couple of examples, and I would love to know what you think about this because I’m still kind of workshopping it, but there are pushes for this for 529 plans, which is like the college savings account, to be able to be applied to a bunch of new programs. There is data that shows that 25% of online college enrollments are actually paid for by employers. So that’s like Amazon, your employer paying for you to enroll somewhere to reskill or upskill. In Singapore, they rolled out a re-skilling allowance, so everybody, I think they actually made it 30. It started at 40, but now it’s everybody over the age of 30 who wants to re-skill, gets a monthly allowance for re-skilling. From the state or the city, they’re getting this re-skilling allowance. In Sweden and France, they have different versions of this as well, where you get an accruable account of training credit. In Korea, they’ve had a lifelong education promotion plan since 2002, which includes a voucher system and a national “Tomorrow Learning Card.” I’m thinking like an abundance framework really means rethinking funding streams at such a grand scale and who schools serve that maybe you’re an adult and you’re wanting to go either change your degree or just enroll in something and you think about your local high school that has a skills center and has this kind of thing, and you can go and actually purchase training from them, which then adds money into the school system again. It’s not a student, but suddenly your student body has gone up by so much if you start thinking about it that way. That to me is a really good example of shifting from a scarcity to an abundance mindset in a pretty tangible way. But I’m super curious, what do you think about that?

Nate McClennen: Yeah, that’s interesting. I think in some ways higher ed has done this already, right? Because they offer non-degree, non-credit courses. Anybody can take them. So they’re a good example of a university, especially if they have an online component, which almost every university does now, has turned into a learning center, cradle to grave. But K-12 is not like that at all. So I think you present an interesting argument that can schools expand to be upskilling for more diverse members of the community, like not just your K-12 students.

I think it’s a really interesting piece, and maybe just maybe if we go back to the abundance piece, which I think is your hypothesis here, is that ESAs are challenging to a number in the public sector for sure, and I understand why. But if they cause the public sector or the public district to open up its walls for more interesting opportunities to bring funding back in, maybe that’s the start of a learning center instead of a high school.

Mason Pashia: Well, it goes back to your learning spaces conversation from earlier, and I think you’re absolutely right that higher ed has paved this way. But I’d actually be really interested to see a radius map of where physical colleges are and where the gaps are and where the K-12 schools are in comparison. I do think colleges will probably win at an online offering level. I think that’s just gonna be a space where they have a little bit more maybe authority or something. But I think that the physical asset of the school building and the things that are in them are really useful spaces for cultivating this kind of re-skilling. I don’t know, just something I was messing with this week and was pleased to see that the actual funding stream solution has been at least addressed in a number of places around the world, and then it’s just a matter of opening your walls.

Nate McClennen: Right, and it is a fundamental shift, and this is what’s hard for a lot of people in education. It is a fundamental shift to sort of a market economy for education because you’re suddenly operating a bit more like you offer a lot of programs and there’s other people that offer programs, and how are we competing? Personally, I think competition helps. I think it does up the ante in our area. We have a lot of competition, and that’s increased the quality for all sorts of students. I think that’s important. Obviously, access is a really important piece, and thus the public sector is so important. It does make me think a little bit about Roscoe Unified down in Texas. Texas actually has some great laws to allow for early college and allow for high schools to offer that. Roscoe is part of a collegiate education, which is a larger network of rural schools. They allow students to stay one to two years after graduation but in the building to complete their associate’s degree. Or if they’ve already completed their associate’s degree through grade 12, they can stay for 13 and 14 and get a bachelor’s degree without leaving their hometown, which sometimes, especially in rural spaces, is a challenge because people don’t want to leave or they have commitments to family or ranching or farming or whatever the case may be. So this idea of being able to offer a broader and more expansive view of education to help people get what they need and the upskilling they need directly in place through a learning center, usually used to be called a school, is really interesting.

Mason Pashia: No, I think that’s really interesting as well. Well, I’m writing a blog on it right now to see if I can make my thoughts make more sense, but would love to keep riffing on that because I think it’s an interesting abundance frame.

Nate McClennen: There’s probably, I bet you if we looked around and maybe listeners can send us a note if you hear this, but I bet you there’s more examples than we know of, especially in the urban sector and maybe in the rural sector, of schools serving as community learning spaces. I know there are districts that do parent upskilling, and they offer parents courses and classes in their buildings just as much as they offer students. I think it tends to be school-day isolated, like that happens in the evening and the students during the school day. So let’s keep looking, and maybe we’ll find some other interesting examples.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, would love more of those.

AI in the Workplace: A Study on Efficiency and Emotions

Nate McClennen: My last news item for this session is you and I are both fans of Mollick, and he’s writing extensively on AI. I really love his blog, One Useful Thing. He just did a study as part of his work at Wharton at Penn, and the study did this: they basically took a bunch of employees of a company and gave them a project to work on, and they determined a set of outcomes that would measure the quality of their outcomes. So they had a quality measure that was verified and similar across their different groups, and they did three different treatments. They had individuals that had access to AI, like ChatGPT or Claude or something like that. They had a team of individuals that didn’t have access to AI, and then they had a team that was assisted by AI. They all completed the same type of project, all measured in the same outcomes. Really cool study. Here’s the conclusions in a nutshell: the AI-assisted individuals, their output or their outcomes were the same as the non-AI use teams, which is really interesting. So just if I’m an individual and I can use AI as a thought partner and use it effectively, my outcomes were equal to a team of humans that didn’t have access to AI. However, when they gave AI to the team, the outcomes were even higher than those original, those other two, the AI-assisted individuals and non-AI teams.

So the AI assistance and the reason, the descriptions of why were that things were more efficient in the AI-assisted teams. Especially when the project was cross-discipline expertise, boundaries vanished. If you were a group of folks that were just focused on biology and your project needed more than that, the expertise you could get from your AI assist. It added for better outcomes that way. The last conclusion, which I thought was really interesting, is there was an increase in positive emotions with AI support, which is a little bit contrary to some of the other research we’re seeing. But they felt like it was an easier project to complete. They felt more positive about the experience. Perhaps this is an indication of how we use AI well. It’s not a replacement for humans, but it’s an enhancement for humans. Especially when we have, going back to the very beginning, what we were talking about, Mason, was this idea that it’s hard to keep up with everything and we all have gaps in our knowledge. If you can add an AI, which has access to a huge amount of knowledge that no one individual could ever learn, that fills some of those puzzle pieces to make a better product in the end. I think it’s worth reading. He writes really well and can summarize it really well. But this idea of democratizing expertise, enabling more employees to contribute meaningfully, really interesting conclusions. Certainly just one study, but it made me think about schools and how we use AI in schools and how we teach students to collaborate with AI in interesting ways and how we teach students to collaborate with each other and with AI, which I don’t think is happening very much. We need to continue to think about what’s uniquely human.

Mason Pashia: For sure.

Human Connection in the Age of AI

Mason Pashia: Well, that brings us very neatly into our landing zone. We’re going to do our quick what’s human section. I’ve got a couple. We did a podcast with Isabelle Hau about her new book on early learning and AI. It was super interesting, but she and I kept riffing after the conversation about this idea of AI readiness, kind of similar to my earlier themes. It just brought this story to mind that I’ve heard a bunch of times from people like Cal Newport and Kevin Kelly and these authors. They always use the Amish as a really interesting adoption story for technology. Because if you look at the Amish, the knee-jerk is to say that they actually don’t accept technology. They live a life sort of free of technology after a certain point. Because you could make the case that a lot of things are technology, like a wheel.

Nate McClennen: Yeah. Right.

Mason Pashia: But they have these really harsh lines from the outside, but when you actually talk with them, what they say is they adopt technology that strengthens their culture and their community values. So you’ll see people there that have rollerblades, that have solar panels, that have some things that you’re like, “Oh, that’s interesting. I wouldn’t have guessed that they did this.” But the reason they would go for rollerblades rather than a bike is because a bike takes people way too far from the community and they want to stay close together. They don’t take these other phones because it just widens that circle of community and cultural values. I think there’s something to that’s really interesting because I just, at these conferences and everywhere, I’ve almost started doing a little bit of a drinking game with myself whenever anybody says, “Start with why.” It is usually used in this kind of way where it’s like just a passing tone. You’re just like, “Oh, I’m gonna say this and then move on.” But this is a really interesting example for me of starting with why when you’re adopting technology, when you’re bringing anything into your school culture even, what is it going to do to our culture and how can we make sure that it is positive and supportive of our end vision? I don’t know, it just kind of was rattling around my brain, but this piece about humans and being able to really dial that in jumped out at me this week. What do you think about that?

Nate McClennen: Yeah, no, it makes sense. I hadn’t really thought about the Amish analogy and this idea of adopting for a purpose. You use it, but it doesn’t break your mantra of, “Hey, we want to keep our community together.” Solar panels and rollerblades, yet… I’m not sure what that is. Solar blades.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, that sounds good and dangerous.

Nate McClennen: When we were traveling last week, while going to these places is amazing, it is meeting people that’s the most interesting part. Even just the taxi drivers or the shuttle drivers and just interacting with humans who are different from you, who you don’t know, and what you can learn from them and what they learn from you. When we went into Guatemala, we flew into the airport and took an Uber over to Guatemala City, which is about, I don’t know, a 20-minute ride. By the end, we had figured out a great restaurant to go to that we never would’ve gone to. It was on the rooftop of this random building, and he said, “Here’s the address, here’s where you should go. It’s really awesome.” We never would’ve experienced that. It goes back to the relationship, and no matter how much AI is going to replicate relationships, it is going to be really difficult to replicate that human-to-human interaction when you’re moving around geographically in a space, in your community, in your world, interacting with your neighbor, interacting with someone in Guatemala, whatever the case may be. I’m still a firm believer that that’s gonna keep us human.

Mason Pashia: I totally agree. I think that solar blades might actually be the winged sandals that Hermes, the Greek god, wears. That seems right, and I’ve wanted those ever since I saw Hercules when I was about three. So if anybody’s listening and is really good at design and machines, would love some solar blades.

Nate McClennen: All right. So our takeaway from this entire podcast is that you should go and create or find solar blades. If you do, let us know where they are, and we’ll do a quick description on our next podcast.

Mason Pashia: I’m sure you’re gonna need an AI team to do it, so be sure to bring them in.

Nate McClennen: Definitely. I’m gonna need an AI team to do it for sure.

Mason Pashia: Amazing. Well, thanks, Nate. Always great catching up. Glad to have you back.

Links

- Watch the full video here

- B-Flation: How “Good” Grades Can Sideline Parents

- Learning Lab Wichita

- In the City by the Sea, a Civic Upswing is Underway

- Transforming Public Education: A Blueprint for Learner-Centered Change

- ExcelinEd’s Pathways ROI Analysis

- CoSN Leading the Way in AI for K-12

- Empowering Learners for School, Work, and Life: Insights from the Research Practice Collaborative (Phase I)

- Aotearoa New Zealand’s rationale for micro-credentials

- Reinventing the Traditional HS Diploma: New Zealand

- New Zealand Record of Achievement

- The Cybernetic Teammate

- Relationally Responsible Tech: Designing a Digital Future That Puts People First

Nate McClennen

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.