Why Learner Wallets Will Fail (And How to Make Sure They Don’t)

Key Points

-

Effective learner wallets must focus on student identity, self-reflection, and intrinsic motivation rather than just workforce preparation.

-

Incorporating engaging, habit-forming elements like mini-games, avatars, and rewards can make these tools appealing to younger users.

By: Mason Pashia and Beth Ardner

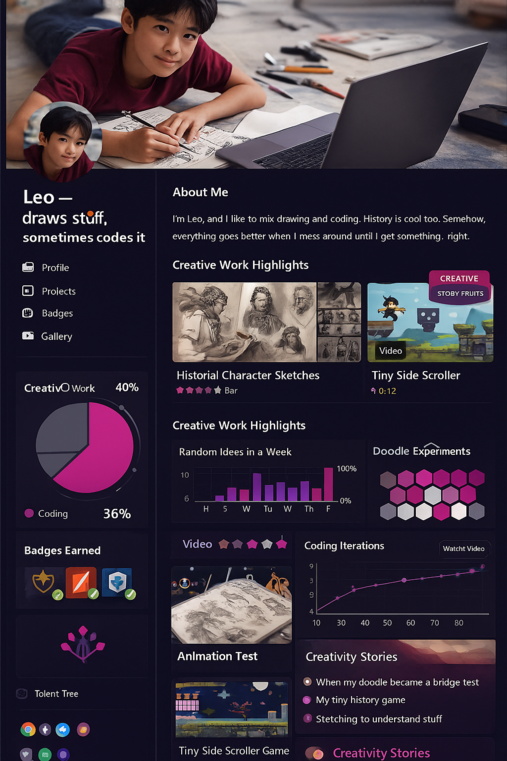

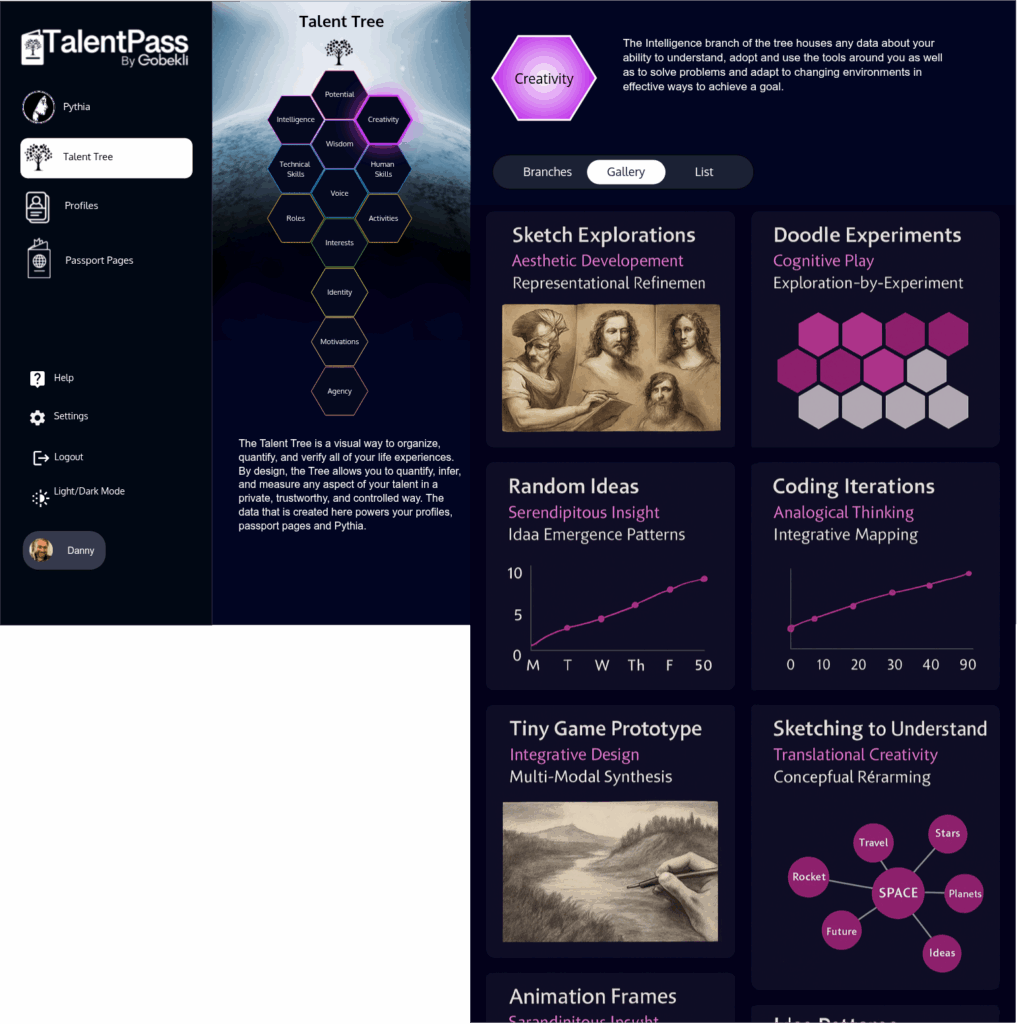

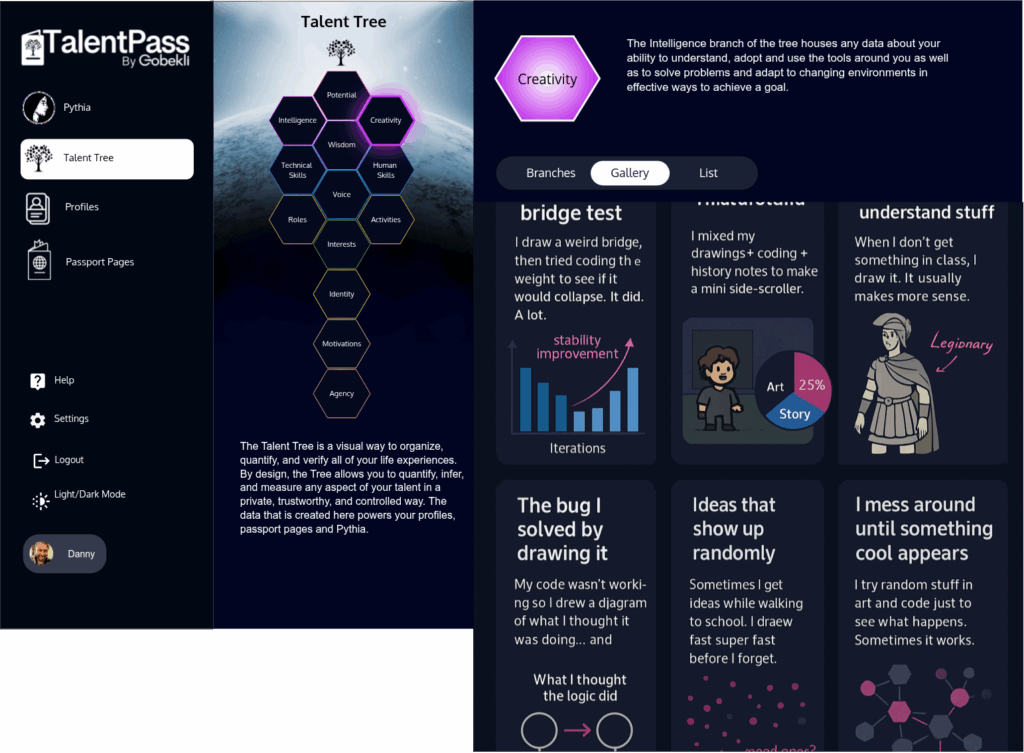

Images are from TalentPass by Gobekli

The infrastructure for learner employment records (LERs) and digital credentialing wallets has a lot of momentum. State legislation is passing. Workforce partnerships are launching. Data interoperability standards are being finalized. The employer validation work is underway.

And none of it matters if nobody uses it.

I (Mason) have tried to set up my own learner wallet multiple times with various emerging tools. Each time, I give up. Filling in the gaps of prior knowledge and experience is incredibly tedious, no matter how good the UX is. If someone who’s deeply invested in this space doesn’t find value in maintaining their own wallet, why do we think a 16-year-old will?

The uncomfortable truth is that we’re trying to create a tool the industry needs, not one people need.

We are creating the equivalent to updating your resume when we should be creating something that that people would use even if no one was looking—in the way that my father-in-law is obsessed with reaching his 10,000 steps goal, in the way we add books to Goodreads but neglect the apps social features, in the way that horoscopes and personality tests make you feel useful and articulate.

The sector is creating tools that summarize identity rather than tools that form identity.

Think about the apps that people actually use every day:

- Snapchat streaks: Social commitment and loyalty as identity

- Pokémon Go and Spotify: Collection and cataloging as identity

- Duolingo: Continuity and learning as identity

- Enneagram and Myers-Briggs: Language and understanding as identity

- Strava: Performance as identity

None of these apps sell themselves as “preparation for your professional future.” They work because they tap into something deeper: the fundamental human need to understand, craft, and articulate who we are, all while being within full control of the user. This means radical control over privacy settings, data sovereignty and more.

The starting place for building value isn’t “this will help you get a job in 2032.” It’s “I documented this thing because this is who I want to be” or “I documented this thing because this is who I am.”

We wrote a hypothetical scenario set in the fictional 2040 that shows how someone might live alongside an LER in the future, but in this blog, we’re digging into the mechanics behind the tool itself… with another hypothetical story, of course. How could you not want to meet Leo?

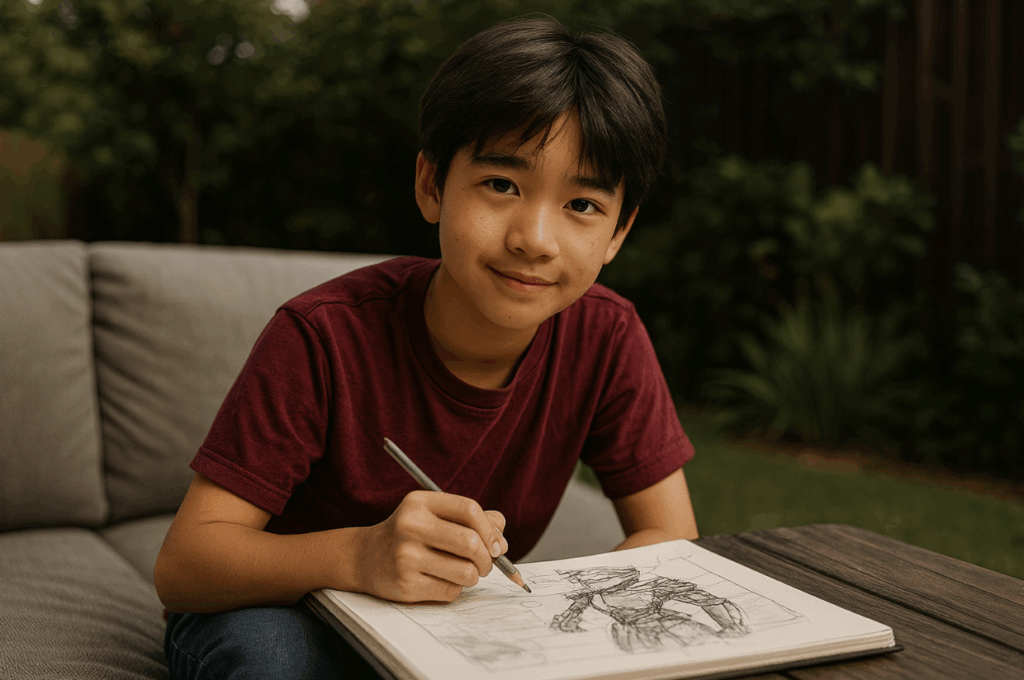

Meet Leo: The Storm Chaser

Leo is 16 years old and feels scattered. He likes coding, sketching, and history, but his teachers tell him he needs to “focus on one thing.” He feels guilty for jumping between hobbies and often thinks he’s lazy because he can’t stick to a schedule.

Leo is exactly the kind of student who would benefit most from a wallet—but he’s also exactly the kind of student who would never voluntarily populate one. Not because he’s unmotivated, but because we’re asking him to document his learning journey for a future employer he can’t yet imagine, using a tool that feels like homework.

Let us show you what happens when we design for the learner first:

When Leo first downloaded the app, he didn’t take a survey. He played a mini-game where he had to choose how to solve a problem.

- Result: The app assigned him his current Archetype: “The Storm Chaser.”

- The Description: “You thrive in chaos. You don’t walk a straight line; you gather energy from variety. Your superpower is Synthesis—connecting things that don’t belong together.”

- The Visual: His avatar is a rogue-like character with a cloak that constantly shifts colors.

Here is a week in his life.

Monday: Creative Flow

Leo sketches in his notebook during Math class. He feels guilty, but he’s “in the zone.” His app passively detects creative apps being used during school hours and rewards him with “Aether Dust” (a creativity resource).

Then comes the critical prompt: “Your Creative Mana spiked during school hours. What triggered the flow state?”

Leo chooses from multiple options:

- I was bored/avoiding work

- I had a sudden idea I couldn’t lose

- I was stressed

This matters because he’s learning to distinguish between avoidance and inspiration. That’s metacognition. That’s the kind of self-knowledge that will serve him in any future career—but it’s valuable right now for understanding himself. He selects “I had a sudden idea I couldn’t lose.”

Tuesday: Building Resilience

Leo has to study for the math test he’s been dreading. He turns on “Dungeon Mode” to focus for 45 minutes. The app’s timer completes, and he receives a “Stone of Will.”

The prompt: “Boss Battle Complete. You defeated ‘Procrastination.’ What weapon was most effective?”

Leo tags his response: #LoFiBeats #PhoneInOtherRoom

He’s identifying environmental conditions that help him focus. Not for a college application essay, but for the next time he needs to study something difficult.

Wednesday: The Failed Test

Leo bombs his math test. He feels stupid and overwhelmed. His app lets him log a “Failed Quest,” turning his negative experience into a “Cracked Shield” (a resilience item he can use in the future).

The prompt asks: “Damage Report: You took a hit. Where was the breach in your armor?”

Leo realizes through his own reflection: the problem wasn’t “I’m dumb”—it was test anxiety. He’s not building a credential for an employer; he’s building self-awareness.

Thursday: Processing Emotion

Leo is still stinging from Wednesday’s failed test. He isolates himself. The app invites him to visit the “Campfire” where he can see others struggling too. He earns “Empathy XP” and his avatar’s lantern begins to glow.

The prompt: “Your energy feels low today. If your avatar could speak, what would it say?”

Leo records a voice note: “I just feel like everyone else gets it faster than me. I’m tired of trying hard and still failing.”

He’s practicing naming the emotion, which is the first step in regulating it. This is social-emotional learning happening organically, not as a checkbox on a rubric.

Friday: The Synthesis Moment

Leo uses geometry concepts in his art project, and it looks awesome. He posts a photo. The app recognizes the tags #Math and #Art and gives him a “Synergy Bonus.”

The prompt: “Wait… did you just use a Skill from a different class? How did [Math] help [Art]?”

Leo responds: “I used the tessellation patterns from the textbook to make the background cool.”

This is transfer of learning—the holy grail of education. And it happened because the app made him want to reflect on and document his learning journey, not because some future employer might care.

While this is one example, deeper gamification and UX will ensure that learners from a range of learning modalities have ways to engage.

A Work in Progress

If we’re serious about making LERs work, we need to invest in understanding the human, not just the infrastructure. Below are research and design recommendations where, as a field, we need more information before designing a lasting tool.

1. Understand The Art of Self-Reflection

Humans are inexperienced at self-reflection. What can we learn from counselors, neuroscientists, journalists, and coaches about asking the right questions at the right time? How do we ensure that metacognition remains a core part of the human-in-the-loop, and it isn’t just AI sorting experiences into skill buckets in a black box?

The metalearning is arguably the most important part. It’s also where learners build the confidence and articulation that—so long as social capital remains critical in hiring—may be even more important than the accompanying wallet.

2. Identify Which Evidence Actually Matters

The skill extraction space is flourishing. AI tools can ingest vast amounts of data and produce confidence ratings indicating how likely someone is to succeed at a task. But which types of evidence and metadata are most valuable? Supervisor validation? Multi-media documentation? Richness of the story? Who controls the evidence and data created? Who owns it?

More importantly, how do we help the human at the center know how to develop themselves to their own benefit, rather than checking boxes according to a formula set by the system?

3. Investigate The AI Companion Question

We’re seeing significant signals about AI companions and youth. In many ways, these will be the greatest source of data for incremental growth along learning journeys. But there’s also huge resistance to them—and justifiably so. Many young people are deeply suspicious of AI and the surveillance implications of these tools. This makes sense. They have seen the effect of data misuse and are eager to avoid losing even more control. The addition of AI to the data privacy equation may require a cultural shift of attitude toward self-sovereignty.

Rapidly, however, this becomes an equity issue. Surveillance tends to affect some communities more than others.

4. Develop New Forms of Data Ownership

Today, the data within our education and employment system is owned by everyone but the individual. Want your college transcript? Good luck. Want employer validation? Enjoy the game of phone tag. We must experiment with data self-sovereignty, interoperability and ownership to create tools where users have full agency over what is visible. Doing so enables equity by allowing people to pick and choose what they surface in meaningful ways. When you can’t be punished with your data because someone else has taken it and used it inappropriately, the danger lessens.

5. Start With Student-Led Design

What would it look like to give this design prompt to students? Organizations like iThrive Games understand the benefits of letting learners problem-solve through game design. If we are to create a tool that teens use daily, do we really think adults will be the best at implementing it?

The Path Forward

As Audrey Tang, former Minister of Digital Affairs of Taiwan, says about updating their civic process, it should be Fast. Fair. Fun. We need adoption with self-attested information first, and data APIs second.

The data work is slow but underway. The momentum has started in the education and workforce sectors, and most players are committed to interoperability. But none of that infrastructure matters if we can’t answer the fundamental product question: How do we make this a habit-forming and generative tool for 13-15 year-olds? The answer isn’t to build a better resume. It’s to build something that helps young people answer the question: “Who am I becoming?” The employment benefits are a side effect of good learning design.

When we solve that problem, the workforce problem gets a heck of a lot easier.

The learner wallet isn’t just a new way to store credentials—it’s a mirror that helps young people see themselves clearly in the past, the present, and in the future. Let’s build tools that are worth gazing into.

Signals from the Future

Gobekli’s TalentPass (pictured throughout) is a Universal Talent Passport that empowers you to navigate your future, adapt, and thrive. It offers a private AI-powered profile for growth and opportunity, with full control over your data and destiny.

LearnCard’s Lifelong Learning Passport is an open-source digital wallet that can connect to any system, designed for IDs, Skills, and Learning and Employment Records (LERs). It is a Lifelong Learning Portfolio.

SuperBetter is a gamified experience that builds resilience – the ability to stay strong, motivated and optimistic even in the face of change and difficult challenges. Playing SuperBetter unlocks heroic potential to overcome tough situations and achieve goals that matter most.

Pokémon Go is an augmented reality phenomenon that swept the nation, gamified into weekly and seasonal challenges that show what’s possible with thoughtful and adaptive growth challenges and structures.

Apple’s Health App is an intuitive tool that gathers data from all kinds of sources: verified, self-attested, actively tracked (Strava, AllTrails, etc.) and passively tracked (pedometer, Apple Watch, etc.). It is, first and foremost, of use to the user.

Agilities from the DeBruce Foundation are an early example of narrativizing skills into making them a core part of your identity.

Beth Ardner is the Vice President of Growth at Gobekli.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.