Generations of Making “the World the Way it Ought to Be” | A Conversation with Generations of Jeffco Open School

Key Points

-

Building strong relationships and trust with students is essential for fostering a learning environment where students feel empowered to take ownership of their education.

-

Incorporating student voice and interests into the curriculum can lead to more meaningful and engaging learning experiences.

A year or so ago, the Getting Smart team was in Colorado for a company retreat, and while we were there, we had the chance to stop by the Jeffco Open School, a school we’ve featured on the site a few times due to its incredibly learner-centered and experience-forward design. I’m excited to dig a little deeper into the Open School model today, and we have the extreme privilege of hearing from multiple generations of people who have been informing the school and benefiting from the school. So today we’re joined by Jennifer D. Klein, a graduate from the Jeffco Open School and current educator and innovator, as well as a previous Getting Smart podcast guest.

We’re also joined by Melyssa Dominguez, the current principal of Jeffco Open School. In preparation for this interview, I was digging around in a couple of books and I saw that Arnie Langberg, the founder and high school principal when Jennifer was a student, recently put out a memoir in 2022. He’s such an incredibly important figure in education innovation that I wanted to start off with some of his words today.

So from the acknowledgment section of To Create the World That Ought to Be:

I have been an ‘educator’ for more than 60 years. I put that word in quotation marks because it suggests a one-way experience from the teacher to the learner. I believe education is a reciprocal endeavor with learning taking place among all of the participants, myself included. I will offer two examples.

One is from my first teaching job. I was a math teacher who was assigned to take over a struggling English class. I negotiated with the students to find a mutually agreeable way for us to explore the English language, beginning with spelling, which required some diplomacy, and then moving into poetry, an even bigger stretch.

Through this, the students taught me how to teach and I taught them how to be literate. A second example took place in Denver. In a discussion among 20 students of a Hemingway story that had often been described as one of the best short stories ever written, I had told the class that I had not found it quite that good.

Our discussion lasted over an hour, and the feeling was so intense that it seemed no one stopped to breathe. The discussion was that good for all of us, and from my students, I gained a deeper appreciation of the story. This reciprocal learning is my rationale for not selecting single students for acknowledgment but rather thinking of all my students from over the years as being part of my own education.

That was Arnie Langberg from his book “To Create the World That Ought to Be.”

So Melyssa, I love this, and I love Arne’s focus on student voice and the learner design of the program. A huge part of Jeffco’s model is the learner design passages that each student undergoes as a student there. Can you describe the philosophy of the learner design passages?

Melyssa Dominguez: Yeah, absolutely. So passages at the Open School are very much meant to be an expression of the student’s experience and their experience of several different domains. So there are six passages in six different domains. Each passage has its own set of requirements that go with them. The student, in consultation with their advisor and a consultant, sort of conceives of what they might want to investigate.

There could be, for their logical inquiry passage, they’re doing an investigation that involves a scientific method. For their creativity passage, they’re taking something that they know how to do to a level of excellence. For a practical skills passage, you’re doing something that people have always done, perhaps for you, and you’re learning how to do it yourself.

So those are just some examples. A global awareness passage is, I’m taking an issue in the world and I am acting locally and I am teaching others about that globally, or I’m teaching about what that passage is, and so each of those passages have their own requirements, their own focus, but they come from the kids’ own conception. So they, we try to give kids lots and lots of experiences so that they can think about what they might care about enough to do a global awareness passage on, and that they want to teach other people and they want to go out and do action about.

And so we try to give them lots of experiences of the world. Like maybe we take them down to the border on a Borders trip, which had a class that was surrounding it, and maybe they get the opportunity to talk to people on both sides of that issue and both sides of that wall. They get to go to both sides of that wall.

They get to both deliver water and also talk to people who are against the people who are delivering water, and creating that opportunity for people to be, to have water sustenance in the desert. And then maybe a kid is inspired by that passion, with an experience like that. And that’s just one very small example of how that might happen. And so it comes from the students’ ideas of what they care about. At the Open School, we make a practice starting when kids are, say three years old in preschool, of asking kids, what do you care about? What might you be interested in? What might you even be passionate about? I think a lot of times kids don’t necessarily know that right away, but they learn it. Yesterday I was in the preschool, and the advisor in the preschool was having a conversation in a circle, teaching kids so many things about being in a circle, about holding a talking piece and sharing what they wanted to share.

And what they were talking about was, what do you want to be when you grow up? And it was a really sweet conversation to experience. And it was just such a validation of what I definitely think, which is that we are asking really young kids from a very early time, what do you care about? What do you see yourself doing? What do you think you might do in your life? And so yeah, so the philosophy is all about helping kids to own their own education and to express what they care about and really dig into it in a very meaningful way to them.

Mason Pashia: Yeah. Amazing.

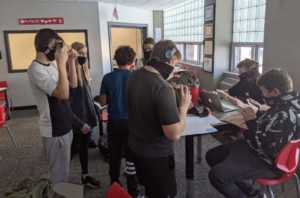

Visiting Jeffco Open School

Mason Pashia: Yeah, we got the, as I mentioned earlier in this episode, we got the chance to visit a couple of months ago as a team, and we got to talk with a few of the students and also see some of their incredible transcripts that I think are really representative of a lot of what you just shared… both the emphasis on valuable and a diverse set of experiences, as well as really tapping into what do you care about. So Jennifer, this is the first time you’re meeting Melyssa, but, as a student, you had some of these experiences. How is what she says? How does that ring true for you, based on your experience? And talk a little bit about some of those passages or projects that you worked on.

Jennifer D. Klein: Absolutely. It’s really interesting to reflect back because I was in high school. I was at the open high school, would have been 1983 to 86, right? So this is a little bit back in the history, not at the very beginning or anything like that, but I was remembering a couple of passages in particular.

And I was just trying to remember whether this was creativity or career exploration. I think it was probably a little bit of both, but I’m not positive. But I knew from very young that I wanted to be a writer. And that was really affirmed for me during the, what Arnie used to refer to as the disorientation experience at the beginning of 10th grade when we went to the wilderness and hiked up Mount Evans.

And I had some experiences there that really sealed that writing was what I was the most passionate about. And so my passage connected to this was all about the practice of actually being a writer. I found a call for submissions in a magazine that I thought was cool. At the time, looking back, it was probably not the best one. It was 17. It was probably not where I actually wanted to put my fiction, but I spent time looking for what was the magazine I wanted to send to? What were their requirements and expectations for writers? Took a piece of short fiction that I’d written, went through a whole extensive revision process with peer reviewing and adult reviewing and improvement over time.

I also interviewed an author, and at the time it was local author Joanne Greenberg, who I believe even lived in Evergreen at the time. Wonderful novelist. It was a challenging interview. She actually really challenged me in the sense that she ended up saying, you should really read my biography before you call me for an interview. And I was mortified, but it taught me something really important about, you learn as much as you can, and then you interview somebody so you can ask questions that you wouldn’t get from the biography. I went through the whole submission process as well. And I even remember I didn’t get the story published.

Not a super happy ending, but a very real one over the years that certainly happened since, and I do remember that Arnie Langberg even bought me several books before I headed off to the Middle East to complete three other passages over the course of eight months. He really wanted to inspire me as a writer and to get me thinking about other kinds of cultures and other ways of writing and thinking about fiction.

So that was a really powerful experience, obviously taught me a great deal about what it means to be a writer. But also gave me really practical experience doing it and knowing what that life might look like.

Global Awareness and Service Projects

Jennifer D. Klein: The other one that I want to spotlight was my global awareness passage because this one actually deeply influenced how I think as an educator today as well. Global education is one of my areas of expertise. It’s one of the areas that I’ve published in, and it’s something that I definitely came from the open school experience. No question. So my global awareness passage in 1985 was focused on the Ethiopian Jews who had just been airlifted out of Ethiopia in 1984 and were facing some really interesting social and political challenges to their citizenship in Israel. I was particularly passionate about that idea.

I knew that some of the issues were connected to racism. Some of them were connected to whether they were truly ethnically Jewish in the same sense as other members of that community. Since then, my relationship with Israel and Judaism became much more complicated after I spent time in the region again.

I don’t want to go too deeply into that story. But I did feel what I did was I explored their, I tried to understand as much as I could about their experience. I came up with an advocacy or service project that would provide clothing and shoes and things like that for Ethiopians living in refugee camps in Israel, Palestine.

And then took a little presentation on the road in Denver to different high schools, talking about sharing my learning, talking about their needs. And then a Jewish group here in Denver took all of the donations that we gathered to them in the region. So again, I think, I think it really impacted the way I think about service, the way I think about advocacy, the belief, the strong belief that I have, that when you think something is wrong, you have to do something about it.

And definitely impacted my sense of equity and the way I think about global competencies and intercultural competencies. So those were two of the powerful experiences I had. If anybody is curious about the longer story, about six months in the Middle East and two months traveling through Europe, I just published a short piece about it in Barbara Bray’s new book “Grow Your Why.”

And I’m very proud of the piece, but it’s, yeah, I’ll stop there and let that story rest.

Mason Pashia: Awesome. I’ll be, we’ll be sure to include a link to the Barbara Bray book in the show notes, but those sound like such valuable experiences in learner agency and just exposure, awareness of the world. That’s so cool. Thank you for sharing, Jennifer. I love the way that those experiences that you frame, those experiences having their, how they have informed your current life, particularly with regards to service.

Melyssa, is that something that you all talk about at the school about how these passages are not like a one-time kind of transitionary protocol? It’s more like something that you iterate on and keep doing your whole life.

Melyssa Dominguez: Absolutely. It’s so interesting ’cause I have the privilege these days of reading every transcript that students write at the open school. And it is one of my very favorite parts of this job because I have my notes that I wrote about reading transcripts last year, which was my first year to get to do that.

And I just feel like each one of those transcripts is like a novella, like a novel about this kid and their experience, and it’s just so exciting to see. But one of the things I asked kids, I had a little box of questions.

Graduation and Transcript Stamping Ceremonies

Melyssa Dominguez: We do a ceremony and I don’t know, it would be interesting, Jennifer, to know what this looked like when you were in school, but we do a transcript stamping ceremony.

When I became principal, the principal before me ceremonially passed the stamp, like the embosser, to me at graduation. So we do this ceremony called the transcript stamping when your transcript is final and you’re ready to graduate at the end of the year, after it’s been read by your advisor and a second reader, and also me.

And we do this, and I have a box of questions, and I had kids pull out the questions and then choose the one they wanted to answer. And a lot of kids chose the question, which is, which of your passages will you keep on doing? Which of your passages are gonna go with you?

And I ask that question because I happen to be mom to two Open School graduates, and I am witness to the fact that those passages, that is how they approach learning, just like Jennifer was saying, like it really has informed a lot of how they attack a project or a thing that they think they care about.

They have such a lovely way of doing their own continued learning. Some kids would try do all of the passages and other kids would choose specific ones that they were interested in doing. It was also really cool to hear about your career exploration passage, Jennifer, because not much has changed about that. Kids do a personal profile. They have at least five interviews of other people who are doing this work. They have hands-on experience. They research the path that you would need to take in order to do that career, and they update a resume or a portfolio that they could share with potential employers.

I joked at graduation with the folks who were there that, like kids more often than not, discover a thing that they don’t actually want to do, which saves, families like multiple thousands of dollars in tuition as they have discovered and delved into something and kind of had this dream about what it was, or a projection of what it was, and then went on to discover what it actually was.

And sometimes, like recently, I went to a passage meeting of a student who’s wrapping their career exploration passage in law. And this student is absolutely on the path that she intends to take and has figured that out and did a beautiful internship in a law office and was able to take advantage of that work and is just completely inspired to be a lawyer at this point through this passage work.

So very excited for that student. I don’t know if I answered your question.

Mason Pashia: No. You totally did. I remember when we were there, you were talking about those stamping ceremonies or just the ceremonies at the end and having one of them that was really embedded in the student community where students brought their peers from the school to come and do that ceremony with them, if I remember correctly.

Melyssa Dominguez: Oh yeah, yeah, so a transcript stamping ceremony can be me, the advisor, and the student. That’s one way that can happen, or it can be me, the student, their triad, wh, Walkabout or the Walkabout program is for the 9th through 12th gradesich is a student support structure at the Open School who goes with you to all of your meetings. And it’s a multi-age. So now, right now Walkabout or the Walkabout program is ninth through 12th grade.

And when Jennifer was there, it was 10th through 12th grade, but right now it’s ninth through 12th grade. So they, you have a triad, which is multiple ages of students, so it can be me, the kid, the advisor, all of their triad or their entire advising group and their mother, and maybe grandma’s coming. There can be confetti sometimes and lots of cheers and I ask them questions about their work and what it has meant to them and what their time at Open School has meant to them.

Jennifer D. Klein: I do remember doing this, although I don’t think we called it the same thing. This is 38 years ago, right? So my initial reaction was, oh my gosh, I have no idea whether I did that or not. But now that I’m actually, as you’re describing it, I do remember, and it was, I think we considered it or named it more like a graduation.

It was more like a graduation ceremony, different from the one that happened up in the mountains. Here we actually showed up in nice clothes and were handed a piece of paper. This included a bunch of teachers, a bunch of students, as well as the principal at the time, Arnie Langberg. And it was basically like a defense of everything that one had learned. And what I remember that it happened inside my home. I remember, I think that was a nice touch that it was very personal.

But the other thing that I remember actually was a point in the conversation where the adults were pressing me on, what do you do when you don’t know? And I think what they were trying to do was to press me to admit that I didn’t know everything, which I did ultimately do. I did finally say, look, I know I have to look for resources.

I don’t know everything. I probably was that kid who came across often. I thought I knew everything, and so there was, there were several adults pressing a little bit further. And do you always know how to handle everything? And it was that moment when I said, I don’t actually, but when I face something I don’t know how to handle, I know how to find the resources.

I know how to go find the answers or the advocates, the experts that I need to be able to overcome whatever that thing is, right? So when I don’t know, I figure it out. And I remember distinctly Arnie saying, and you are now a graduate of the open school, because that was what he was looking for, and that’s what the whole community was looking for, was that admission from me.

I don’t know everything, but I know how to work my way through even when I don’t.

Melyssa Dominguez: I think what you’re talking about is your final support meeting. I think that’s what that was. So there we do a lot of rites of passage at Open. And the transcript stamping is a very small ceremony, but the final support meeting is the student’s actual graduation from high school.

And we do, as Jennifer said, a ceremony. We do it now at Genesee Mountain, I think you guys did that then at the, in the meadow there. It’s really beautiful. And what is now Mount Blue Sky used to be Mount Evans, which is right behind where this takes place. And that is where kids begin their walkabout experience.

That’s where they go on this four-day, three-night backpacking trip that starts off everyone’s. Walkabout experience. And then we end there in a graduation ceremony, but they don’t even receive their diploma there. They actually receive it at this final support meeting, which it usually happens here these days.

And it’s in a circle and every person who. It’s two hours long of an opportunity for a student to speak for a good 45 minutes to an hour about their experience, defend their experience, as you were saying, talk about their experience, share artifacts with the group. And then they’ve got their entire family usually and their.

They, their friends, their triad members, their advisor, their consultants, their me. Lots of different people would be there. There’s a, we spend a whole week doing that for every single one of our graduates. At the end of that week, we go up and do a celebratory graduation ceremony up in the mountains.

So yeah. I think you’re talking about your final support meeting. That’s what I think.

Jennifer D. Klein: In which case there might not have been such thing as a stamping ceremony or I’ve completely forgotten it 38 years later.

Melyssa Dominguez: Sometimes it’s kind of a nothing. It just depends on how much the advisor and how much they wanna celebrate that moment. For me, it’s really lovely because I get to do it with every single kid. So it’s a nice time between me and the kids.

Mason Pashia: I feel like every time I hear more about Open School, I wish that I could do the Billy Madison thing and go back to school. And looking at the course catalog, last time I was there, I was like, I wanna take all these classes now They’re incredible. So, I’m just like following the journey of student transitioning from open school into the world (and acknowledging the fact that they never have to transition, right? Like they’re always of the world and the world.)

What happens next? So they have this big transcript, you’ve reviewed it, a couple of people have reviewed it, you’ve stamped it, and then they go into the world with this sort of differently sized transcript than a lot of other people that is arguably much more articulate about the experiences that they’ve had than anything else.

So what happens then? And then Jennifer, I would love to hear your experience of that too, after.

Transitioning from Open School to Higher Education

Melyssa Dominguez: So from my experience, a lot of times a lot of kids are applying to institutions of higher education. And if that’s a place that we’ve worked with for many years, like here in Colorado, there isn’t a higher ed institution that doesn’t know about the open school. So we send graduates their way, applicants their way every year.

But sometimes there are schools that are not here, further away, and a student’s advisor will often make a phone call, talk with, I was talking to a student just yesterday. She turned in her transcript for early submission ’cause she wants to go to Smith. She’s applying to Smith and which is a really big deal.

We’re very excited for her and I think they would be so outrageously lucky to have her. And she’s written a 50-page transcript, which is sitting in my queue to read through. At this point, we’ll stamp it and do all the official stuff at the end of the year, but right now they need to see a preliminary transcript, just as you do when you apply for early submission or early application.

So she, so what’s gonna happen with that transcript and any after graduation as well, is that we will send off that transcript and then that student’s advisor will get on the phone and call an admissions representative, introduce themselves personally, and explain to them what they’re getting in case they haven’t seen one of those before, one of our graduates.

And so talk about how that’s a person. Who they’re gonna learn so much more about what is this document in your hands? ‘Cause every student writes a personal statement. And then as part of their transcript, and then they have what we call now an educational experiences list. And that is something new that Jennifer wouldn’t have experienced necessarily.

It’s a list that, to make it a little easier on those admissions reps so that they can see like a, almost a table of contents, except for it doesn’t have page numbers, it just lists the different experiences in different ways, and then that kids can make all kinds of choices about how they write their transcript.

It can be it’s a narrative all the time. It can be chronological, very, very direct, like a chronological document where you’re talking about your first year, your second year, your third year, your fourth year. You can call them freshman, sophomore, junior, senior if you want, although.

I dunno if you would, but you could. You can call them by the years, whatever it might be. Or it could be organized by some other structure. We’ve had kids create sections of their transcripts based on yoga poses. I’ve seen kids, my own daughter did her transcript based on hiking. She, like the part where you’re getting ready to go on the hike was like her.

First year in school, and then there were like different sections based on, and then she organized her experiences within there. I had a kid last year do a really cool thing about an album a year. So he chose the album that he was really listening to and how that related to the year and represented his experience and then all of the experiences that he had in that year.

He also QR coded those albums. So you listen to. Really next level. So that was really cool. Yeah, so kids do them all different ways and so you don’t necessarily, as an admissions rep, when you’re used to getting like a one or two page document with some letters and numbers on it, now you’ve got this narrative document where you are going to be able to get to know this kid.

’cause they’re gonna talk about all six of their passages. It’s very real and important to kids. And so it’s a great way to get to know people, to find out what their passages were. So anyway, they’re gonna learn all of this about these kids, their own reflections on those experiences, and what they learned in all of their classes, and all of the travel that they did, and while they were here at Open School.

And anyway. Advisor is gonna call and talk to that admissions representative and try and help them understand what they’re looking at and what they might get with an open school grad, as a person who hasn’t had grades all these years necessarily. But is a person who’s probably gonna know their way around navigating and seeing their.

Instructors, their professors as actual human beings that they could talk to because they’ve had this experience of having adults be very accessible to them. And so that’s, sorry, that’s what they think is gonna happen. Do you know what I mean? That’s what that’s their paradigm is that adults are not these scary folks.

They don’t see themselves as separate, we hope. And so they’re, you’re gonna get that. They also know how to get help if they need it. So knowing that person is a human being means that if they post office hours, I might go try to create a relationship with that person and get the support and help that I might need.

So there are people who know how to own their education, so like that.

Mason Pashia: We’ve been thinking a lot about credentialing experiences in learner records the last few years, and in this last year in particular, we’ve seen a lot of really interesting AI-powered solutions that take a batch of experiences and will synthesize a bunch of skills or competencies that come out of that too.

So as I feel like as those tools become more common and more normalized, especially in the admissions process, these transcripts are gonna be such a rich resource to let students communicate what they know and then have other people be do the interpretive work. Right now, a lot of that falls on you to interpret what these experiences amount to in a way that is commonly understandable by the state, but I think that is, close, we’re hopeful that is close and that I think you all in the way that you’re organizing these learning are at the cutting edge of what to capture, how to articulate it, and then empower the students to really take ownership over sharing that.

Jennifer, I would love to hear from you as someone who graduated, how’d that transcript serve you, and do you still think about it today? What do you, how do you think about it?

Jennifer D. Klein: As we’re having this conversation, I find myself wishing I knew where the heck mine was.

I do remember writing it. I remember that it was about 50 pages and I also remember an extra layer of my experience, which was that I had taken the PSATs and had done poorly on them. And I wanted to go to a really high-powered college. And I did poorly because the kinds of things that the SAT tests were not the kinds of things that were really my strengths. I had a high IQ, I had a really creative mind and a very different mind that saw things differently than most people did. And that wasn’t coming through on the SATs. All that was coming through was, I didn’t know this piece of content knowledge.

I didn’t take a class in this, so I didn’t know this thing in history or whatever it might be. And I refused to take the SATs, and it was with my advisor that we came up with a strategy for what it would look like to try to apply to a college in 1986 that would actually consider a student at all who had no grades, no grade point, average of any kind no letters or numbers of any kind on that transcript.

And no SATs to fall back on, right? To be able to understand the student’s knowledge. And so my advisor, who was Rick Posner, who’s written an extraordinary book about the school as well, called “Lives of Passion School of Hope,” which was a longitudinal study of the impact of Open School on graduates.

He and I came up with a strategy and my entrance essay for college was actually on why the SATs couldn’t capture the kind of learning experiences that I’d had and the kind of intelligence that I brought to the university. I think what was really different about the experience in 1986 was that there were quite literally two, maybe three colleges in the entire United States that would consider a student without grades and without SATs.

That’s the good news is that has changed. So at, when I was looking at colleges, my two choices were Bard College and Hampshire College. I perceived Hampshire as a place that would be very similar. To the open school experience. And so I chose Bard because I wanted something more intensely academic.

I wanted something different that would be challenging in a new way. I let, I missed out on a scholarship because of the lack of ranking. And I do remember that Arnie wrote a whole letter about how I would have ranked, or I would rank, he would rank me in the top 10 of my graduating class, but with no letter or number grades to back that up with no GPA and real ranking to back that up.

It didn’t matter that our philosophy didn’t include ranking. So I did miss out on a pretty significant scholarship, which my father still complains about because he felt like that was something that Bard should have been open to in a better way.

So anyway, something that my father is still frustrated by today. But I was able to get into Bard. I was able to thrive there. And I think what you said, Melyssa, about being able to go find the teachers and go advocate for yourself was very true. I actually remember my very first midterm report period. And one of the professors who I had come to really adore and really appreciate had given me a relatively low grade. And it was my first time ever really receiving grades. I had spent a couple of semesters in community college in Denver before I transferred to Bard because I wanted to prove to them and myself that I could get decent grades in a college context.

And because I knew my parents weren’t gonna be able to afford lots of years at Bard, I was trying to cut back on their costs. But I remember going in to see this literature professor and asking him what the grade meant, and his looking at me and saying, it means you got this grade. And my saying, no, sir, with all due respect, I actually have never received a grade and I need and want to understand what this means. So can you talk to me in a more. I don’t know, holistic way about what I did well and what I need to work on and what this grade really represents about me as a learner. And he, fortunately for me, stopped in his tracks, said, “Oh, okay.”

He started having a real conversation with me about the learning process and the kind of writing that was required of literature students at Bard what they were looking for. So I think the, the transition wasn’t easy. I. My whole first year at Bard pretending that I had read all the same literature that everybody else had in the classroom, and I was sitting next to kids from Exeter and Andover academies and places like that who could go on and on about different authors and had read incredible variety of literature.

And I remember sitting in that class and smiling and saying, oh yeah, so true. So like Hemingway. And then I would run to the library after class to read some Hemingway. So I’d know what I’d agreed to, right? Because I had, I just didn’t have that breadth of experience. But as Arnie pointed out to me, even at the time, I remember calling him concerned like, there’s all this stuff I don’t know that everybody else seems to know.

And his answer was did have you been figuring out how to navigate? The situation when those gaps come up, I’m like, yeah I’m figuring it out. And he was like then I win the argument, right? You’re prepared for college, you’re totally prepared for college. And I did learn over time that I didn’t have to pretend.

And I didn’t have to run to the library to find the answers. All I had to do was say, Hey, I haven’t actually read Hemingway. Could you tell me a little bit about why you believe that this author is doing something similar to Hemingway’s style or work? And then it, everything got a lot easier once I learned to be brave and to just say what I didn’t know more openly in a setting where it was pretty scary in that first year.

Mason Pashia: Yeah, that’s a lovely continuation of what you shared earlier about getting to graduate once you admitted you don’t know everything.

Jennifer D. Klein: Yeah. A core theme in my life. I think actually still.

Mason Pashia: I think that should be a core theme in every learner’s life.

Advice for Educators and Administrators

Mason Pashia: So Jennifer, Melyssa, thank you so much for being here today. I want to go to the last question for you, which is, how can the people listening to this podcast begin to implement some of the learnings from the Jeffco Open School? What can an educator or administrator start to do now to really embody some of these things you’ve talked about today?

Jennifer, I might start with you this time, if that’s okay.

Jennifer D. Klein: Sure. I think I channel everything about that I learned at open school in the work that I do today. Because I do support teachers and school leaders in more student-directed styles of learning, more authentic project-based experiential, expeditionary at times kinds of experiences for students.

And I think the most important thing is to ask the kids. To always be in dialogue with the students. I think if there’s anything that the listeners I would hope would take away from this is, tomorrow morning when you get into class, ask your kids what are they interested in, and it’s your job to figure out how that connects with whatever it is that you need to teach and the standards that you need to accomplish.

I really believe that. Bringing students’ voices forward is an essential element of this work. I wrote about this in the landscape model of learning and we referred to it as student protagonism, which we described as the highest level of agency possible. A little like every single student feeling like the Jason Bourne in their own action movie as opposed to feeling like an extra in a movie that’s being put on by the teacher.

So I think that’s really. There are lots of strategies that go along with this in terms of what it looks like to do student-centered evaluation and student-centered ideation and all of those things. But in its essence, the point is to ask the kids, be in dialogue, understood. Understand who they are, and leverage their thinking in the learning process.

Mason Pashia: I hope students are less on the run than Jason Bourne, but just as much of a focus of the experience.

Mason Pashia: Melyssa, how about you?

Melyssa Dominguez: Man. I love what you said, Jennifer. I really love that, and I could not agree more. I think if you can do nothing else, remember that this education that kids are gathering to themselves under your watch, it actually belongs to them. It doesn’t belong to you. And it’s not about what you want to teach them necessarily.

It’s about what do they, what can you convince them that they want to learn? If they are not interested in your subject matter, then it’s your job to figure out. Why does it matter? It does matter. So the subject matter, it matters to do the work that needs to be done for kids to gather the information that needs to be gathered.

And it’s up to us as educators to help them to see why that’s relevant to them and to remember that it will be so much more powerful, actually powerful if they. Understand and care about what they’re learning about. And so asking them what would make it more interesting to them, what it has to do with their own lives, I think is really important.

I think too, it all really starts from a place of relationship. I think in the school district where we are Jefferson County Public Schools in Lakewood, Colorado. And here they talk about knowing students by name, strength, and need. And I love that. I love that the school district is doing that.

I love that’s something that people have in their heads as they’re out there working with kids, but it’s so much more deep than that. It’s so much there. It needs to be so much deeper. I think if schools can do nothing else, they should create. Their advising system to be something that actually seeks to know kids so that they don’t have to be anonymous, so that you can actually have an idea about what they care about and what they wanna learn about, or what they, what would engage them.

Because if they feel. Unseen and invisible, then what is the point? It’s important for kids to be seen. And so I think conventional schooling could get more intense about really doing a system whereby they can. Assure that kids are known in their buildings, and by doing that they’ll know better what they wanna learn and then maybe they can tailor some experiences so that they’re relevant to kids so that they will be lasting.

And you’ll have a person talking about a global awareness passage or some similar kind of experience, 38 years later as they’re living their lives, that it will have actually, that they don’t have to wait till high school ends for life to begin. I think I get really frustrated when people talk about.

Creating only about career college and career and after high school. ‘Cause I just wanna always say you realize life is actually happening now. Like they’re living a life right now. Our students at every age in this building, at every age, in any building, are actually living their actual life in this moment.

And it’s not about preparing to do a thing, it’s about living the life that you have and making that worth living whenever someone comes here to open school. And, or whenever someone asks me a question, they usually don’t come here and ask me this question. It’s usually like an info session maybe, or something about is it possible to graduate early, from the open school.

And my answer to that is it’s not impossible, but it certainly isn’t our goal. We’re not after kids graduating early because we don’t believe that life is gonna begin after they graduate from our school. We think that life is happening right now for them, and we wanna help them make the most of that life.

So I guess I would say. Create relationships with kids. Ask them, just as Jennifer said, and exactly the way that Jennifer expressed it. Ask them what they care about, what they are interested in, what are they even passionate about? And some of them won’t know. I didn’t know when I was a kid ’cause I didn’t get asked enough at all.

So I would’ve had no idea an answer to, what are you passionate about? I might’ve been, say what I maybe was slightly interested in maybe. But most of the time adults were telling me, they were serving me education on a platter rather than inviting me.

Mason Pashia: And so many adults don’t know what they’re passionate about ’cause they never got this experience in school. So it’s full circle. Yeah. Jennifer.

Jennifer D. Klein: Can I jump back in too? And I wanna echo a little bit of what you were just saying too, Melyssa. I think there’s Arnie Langberg last night in an event for what school could be named trust as an essential element as well. And I think it’s that combination of asking students, involving them in a deep way in the choices that are made along the way.

Not just that Popsicle stick, you can choose from these three things that the teacher came up with for you but truly. Making real choices, having those relationships, all of it really does come back to trust. And so many of our systems in education seem to be built around a lack of trust in young people and their ability to think for themselves and their ability to be autonomous, complete human beings with their own ideas about themselves and the world.

And so I think that’s another really important element to go back to always, is how I, that might be a little bit harder to act on tomorrow morning. But I really do believe that building those relationships and building that trust with young people is part of what allows us as more student-centered educators to include them so consistently on a high level in the decisions that are made along the way.

Melyssa Dominguez: Yes. And I wanna build on what you just said because yes, you do need to trust kids, you need to, and we talk about trust all the time. That is a legacy of Arnie Langberg and all who came after him is just this idea of trusting kids and trusting. But I would also say as a school leader, I would say that school leaders need to trust the adults in the building.

The people that you hire, people you can trust to have some autonomy because you can’t expect people who have no autonomy to inspire autonomy in kids. People who are gonna be working with students. Those teachers, and here, open school advisors, they need to know that they have your trust and that you, and you do actually need to trust them because if you’re gonna ask them.

To inspire students who are self-directed and can go out and create experiences that would be really hard for them to do if they don’t feel honored as professionals themselves. So I.

Mason Pashia: Amazing. All right, Jennifer.

Final Thoughts and Farewell

Mason Pashia: Melyssa, it’s been such a treat to spend time with both of you and the multiple generations of open school voices that we got to hear today. I just wanna say thank you for being here and thank you for the work you continue to do to cultivate communities of learners right out of Colorado to everywhere.

Thank you so much for being here today and the work you do.

Jennifer D. Klein: My pleasure.

Guest Bio

Melyssa Dominguez

Melyssa Dominguez first visited the Open School with her two children in the spring of 2009 and has been captivated by this remarkable school and its thriving, vibrant community ever since. She has long believed that the most meaningful educational conversations—those she is most passionate about—are happening at the Open School.

Throughout her time at Open School, she has seen the school from multiple perspectives: as a parent, teacher/advisor, assistant principal, and principal. Over the years, she has had the privilege of traveling with Open School students both close to home and far afield—sleeping in countless tents, on church sanctuary floors, on the moss of the Boundary Waters, and even once on top of a pile of luggage in a bus bound for Washington, D.C. She has witnessed the dedication of Open School advisors and staff as they cultivate deep relationships with students, curate enriching classroom and travel experiences, and work tirelessly to inspire students to think critically and take agency in their own lives.

A few years ago, Open School celebrated 50 years as an Option in Jeffco. With vision, humility, and compassion, Melyssa is committed to ensuring that the school continues to inspire students to create the world that ought to be—well into and beyond its 100th year.

Jennifer D. Klein

Jennifer D. Klein is a product of experiential project-based education herself, and she lives and breathes the student-centered pedagogies used to educate her. She became a teacher during graduate school in 1990, quickly finding the intersection between her love of writing and her fascination with educational transformation and its potential impact on social change. She spent nineteen years in the classroom, including several years in Costa Rica and eleven in all-girls education, before leaving the classroom to support educators’ professional learning in public, private, and international schools. Motivated by her belief that all children deserve a meaningful, relevant education like the one she experienced herself, and that giving them such an education will catalyze positive change in their communities and beyond, Jennifer strives to inspire educators to shift their practices in schools worldwide.

Links

- Jeffco Open School – Jeffco Open School Website

- Barbara Bray’s Book – “Grow Your Why”

- Bard College – Bard College Website

- Hampshire College – Hampshire College Website

- Jennifer D. Klein | LinkedIn

- Melyssa Dominguez | LinkedIn

- To Create the World That Ought to Be: Memoirs of a Radical Educator Paperback

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.