The Equity Continuum: Cultivating an Equity Mindset in Classroom Global Partnerships

Key Points

-

If our goal is to foster global citizens, we need to teach students to engage with the world with their heads, hearts and hands.

-

Here are five reflective questions to explore to help you move your global and local engagement toward higher levels of equity.

By: Jennifer D. Klein

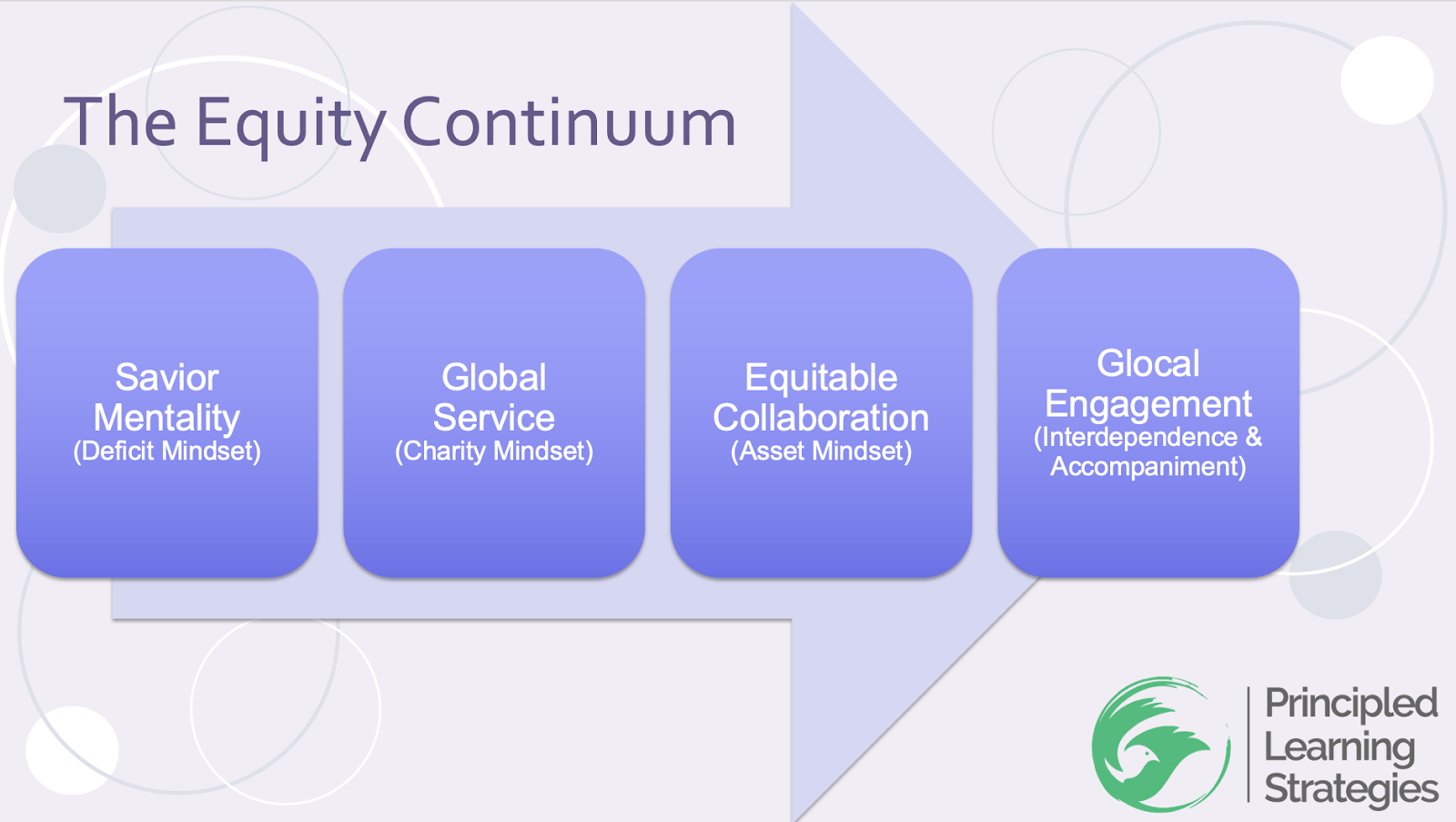

When it comes to equity in global partnerships and global learning experiences, I used to see the challenge in more black and white terms. Either you built a relationship that was equitable, one focused on learning from and with others on equal terms, or you didn’t. But the reality isn’t that clearly packaged, especially in education. Over the years, while I’ve supported global educators through professional learning and my first book, The Global Education Guidebook (2017), I’ve encountered plenty of wonderful educators stuck in deficit mentalities in spite of years of partnerships that appeared to serve students well. I’ve also encountered first-year teachers who are already engaging glocally at the highest levels of strengths-based relationships. There are shades of gray to this, I’ve realized, and all of them are valid and real places to practice global change making with students. But there is a continuum to this work, which I hope helps educators move toward greater equity over time. After all, as I’ve suggested often, inequitable global partnerships in the classroom lead to adults who think in inequitable terms about their relationship with the world.

Level One: The Savior Complex (deficit mindset)

This first level of global partnerships is the lowest on the equity continuum, as it builds inequitable, deficit thinking about our global partners. Born out of a history of colonization, whether we recognize it or not, the savior complex is most common in schools of privilege, where students (and their teachers) set out to save or fix their partners’ challenges. At their best, such partnerships are misguided attempts to solve for others; at their worst, they can convince students that they know what other cultures and societies need, even better than those living the challenges personally. Any time one classroom “adopts” another, with the intention to give them what they need, students may take away a deficit-driven impression of the other culture, as the experience can suggest that the adopted culture has none of the strengths necessary to drive their own improvement. Given that each culture and community has its leaders, and its own ideas about how to solve local challenges, such partnerships dehumanize those receiving support because they suggest that the community can’t do it for themselves.

Level Two: Global Service (charity mindset)

The second level of global partnerships is an important step toward equity because it comes from a charity orientation. Less focused on solving challenges for another community, partnerships at this level focus on helping, usually with funding or other resources, for projects that the community itself has deemed important. The charity orientation exists in almost every major religion in the world, and there is nothing wrong with giving money to an important cause. For example, in the educational partnerships I helped facilitate during the Ebola outbreak in 2014-2015, schools in North America raised money to support the installation and maintenance of handwashing stations across a rural region in southeastern Sierra Leone. The handwashing initiative was the idea of local leaders in the region; students engaged with leaders in a variety of ways, and their charity was to help finance local solutions. These relationships tend to be less equitable because they are still built on the notion that the community needs outsiders to fund their ideas, and can easily build reliance on that funding. However, charity-oriented partnerships are still an important step in the right direction—and as in the case of the Ebola crisis, a very necessary way of supporting local action and development.

Level Three: Equitable Collaboration (strengths mindset)

This level of global partnerships is significantly more equitable because it comes from a strengths mentality, meaning that it’s grounded in the belief that everyone at the table has something to offer as we solve both local and global problems with our partners, not for them. By assuming that solutions will be built through collaboration, and that all partners have something to learn and teach others, equitable collaborations often focus on solving local challenges with the support of global partners. For example, in The Global Education Guidebook, I shared the example of a partnership between a Denver-area school, which focused on solving water quality issues in the region, and a school in Jordan, where students focused on solving local issues with drug addiction. Both classrooms supported each other’s work with their own local perspectives, the Denver kids offering feedback on solutions to drug addiction from their experiences, and the Jordanian kids offering feedback on solutions to water quality issues from their perspective. Rather than solving for each other, such partnerships allow students to learn how to collaborate based on mutual recognition of strengths and the value of diverse perspectives.

If our goal is to foster global citizens, we need to teach students to engage with the world with their heads, hearts and hands.

Jennifer D. Klein

Level Four: Glocal Engagement (interdependence and accompaniment)

This level of partnership takes us to the best possible place: a recognition of our interdependence as humans on a shared planet, and our desire to accompany each other through difficulty. Brought into the mainstream by Dr. Paul Farmer, accompaniment is originally a Judeo-Christian concept; its eastern parallel is interdependence, which we find at the heart of Buddhism and a variety of other eastern religions. The development of an interdependent mindset is all about letting go of ideas of superiority or disadvantage, and really engaging with others as essential partners in positive change. The Sustainable Development Goal #17, “Partnerships for the Goals,” captures this by suggesting that only through partnerships can we accomplish the other 16 SDGs. Classroom partnerships at this level on the continuum look like students co-constructing solutions together, collaborating across cultural priorities and needs, and producing solutions that represent all voices at the table. Climate change projects, for example, often include students in various countries working to address climate change in their own communities, sharing those solutions with their global counterparts, and working with their global partners to co-create presentations and documents to be shared with professional climate change advocates.

Important to this level of equity is the word “glocal,” which intentionally connects global partnerships with local engagement as well. At this level of the equity continuum, students are more aware that most of our challenges are borderless, and that they will find poverty, conflict, discrimination, and other essentially human problems in their own communities as much as in the outer world. At its core, such awareness forces us to stop “othering,” to stop thinking of poverty, for example, as something that happens elsewhere but not in our own communities, and to recognize that superiority mindsets are misguided. To be glocally engaged, in this sense, means to have such awareness, to recognize patterns across contexts, to strive to understand the systems that create these problems–locally as much as globally–and to work together to address our common challenges as equals.

Fostering Equitable Global Citizenship

If our goal is to foster global citizens, we need to teach students to engage with the world with their heads, hearts and hands, as I describe in the Global Education Orientations document I wrote for work with schools. By heads, I mean a “thought orientation” which is about building students’ intellectual understanding of the world around them, an understanding of historical and current events and trends, and of the factors which influence human life on this planet. By hearts, I mean a “value orientation” which is about building students’ humility and openness to consider other’s perspectives, their capacity for empathy and their urge to understand the world through other’s eyes. And by hands, I mean an “action orientation” which is about building students’ ability to act on the issues that matter to them and to do so in a way that builds equity and wellbeing for all. All three orientations are an essential part of building equitable global and local thinking in students, teachers, and school leaders.

While many consider “action” to be a key component of global competency, that action can take many forms—and inequitable action can actually do a lot of harm. In educational partnerships mired in the savior complex, one classroom “solves” the other community’s challenges, often without significant inquiry into their needs and aspirations—and certainly without consideration of that community’s own potential solutions. To avoid building partnerships focused this way, educators can build more community inquiry into the beginning of their engagement. By increasing dialogue between students in different contexts, and approaching such dialogue as a chance to learn about each other, we can move beyond deficit thinking about others.

Even if we still feel moved to fix or save, at least we will do so from a better understanding of what the other community believes needs solving, rather than from our own assumptions about them. Even better, if teachers can provide opportunities to speak with local leaders on both sides of a given partnership, students will come to learn that solutions already exist, and that every community has the ability to solve its own challenges. Such recognition will move a classroom’s partnerships to a higher level of equity on the continuum, demonstrating the power of dialogue to ensure students learn to think of action as a collaborative process, and can see the inherent talents and humanity in every partner they learn from and with.

Sometimes, helping isn’t even part of the conversation. It’s not that I distrust helping; I see empathy and action as a powerful and beautiful urge and seeing people help one another gives me hope for humanity. But one of my favorite global partnership examples had nothing to do with helping. It came from a middle school classroom in Brooklyn that spent a full day with an Iraqi refugee, a young man who had escaped Iraq in the height of the second Gulf War and was now living on the East Coast of the U.S. The students didn’t try to fix or solve anything for him. They prepared for his visit by learning as much as they could about the exodus of Iraqis during the second Gulf War, and by generating questions for someone who had lived through it. On the day of his visit, the students learned from him, asking their questions, hearing his stories, asking more questions that emerged, and sharing their reflections on his experiences and their learning along the way. No action was necessary or desired; it was a day of accompaniment, of walking together and learning from each other. Students did decide to invite him to campus to speak with the whole student body the following year, so there was action, but even that was focused on making sure others learned his story, not on fixing or saving someone who had already saved himself from war.

Designing with the Future in Mind

How we design students’ early interactions with the world matters; these interactions build the foundation for how young people will engage with the world in the course of their lives. If the global competencies they gain in school are entrenched in deficit mindsets about other humans, students are likely to act out the same in their adult lives, which will only exacerbate the inequities of our societies. Instead, parents and educators need to teach their children to build relationships that foster equitable, strengths-oriented mindsets about what humans can accomplish together, global competencies grounded in humility, and full recognition of others’ lives and priorities. If we can do this effectively across schools, perhaps one day our students will do the same across all of our societies and systems, reimagining what might be possible if we ground our work in equity.

Explore the following reflective questions with your school leaders, faculty, and/or grade level teams, to help you move your global and local engagement toward higher levels of equity.

- In what ways might our partnerships suggest that other communities need our help to succeed? How deeply entrenched is that mindset in our work to date?

- How might we create opportunities for more equitable, strengths-based conversations and inquiry experiences that encourage learning from and with?

- How might we help students learn to honor the ideas other communities have about their strengths and opportunities for improvement?

- How might we design our partnerships as co-creations that honor all ideas, perspectives, and contributions?

- How might we foster a mentality of accompaniment and interdependence in our students? In ourselves as educators?

Jennifer D. Klein is a product of experiential project-based education herself, and she lives and breathes the student-centered pedagogies used to educate her. She is a former head of school with extensive international experience and over thirty years in education, including nineteen in the classroom.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.