Focusing on Student Learning Will Attract The Educators We Need

Key Points

-

We need to shift the way we are problem-solving the larger issue and begin with students’ learning needs instead of teacher shortages.

-

When we start broadening what students should learn, we open up possibilities for those who can help facilitate that learning.

By: Michelle Culver

I have deep respect for the way school leaders are problem-solving in the face of today’s teacher shortages: they’re stepping in to drive buses, combining classrooms when substitutes don’t show up, and enlisting central office staff to fill vacant roles. Meanwhile, our nation’s teachers are trying to meet the wide-ranging needs of their students by serving as curriculum developers, mental health specialists, career coaches, after-school tutors and, tragically, public safety officers — all on top of their baseline job descriptions.

It’s triage mode, especially in underserved communities of color and rural districts.

The focus on recruiting teachers to stabilize is understandable and human. However, continuing to approach the teacher shortage as a staffing issue will not create the magnetic school environments that draw in adults, or for that matter, young people. Let’s instead pause to revisit the fundamental question of what young people need so we can give them the transformative learning experiences we’ve known they deserve.

A new problem-solving approach

I believe the better way to solve the teacher shortage problem is to reframe it as a learning design problem: What do young people need to thrive in and shape our rapidly changing world? What if we reconsider the academic silos of math, science, and history to find relevant, integrated ways to deliver rigorous standards? What if schools offer the real-world training and social-emotional skills needed to thrive over a lifetime? What if schools customize learning for students to pursue their own interests?

I’m suggesting we shift from a scarcity mindset (e.g., not enough teachers to meet basic student needs) to an abundance mindset (e.g., a robust community of support for an expanded definition of learning). Doing so is not aspirational — it’s actually pragmatic.

When schools reimagine outcomes, we recognize that some learning is best facilitated by industry professionals, college students, community leaders or others — alongside teachers. A broader and more diverse set of people becomes critical and offers one viable solution to staffing shortages.

A new learning agenda and human capital framework

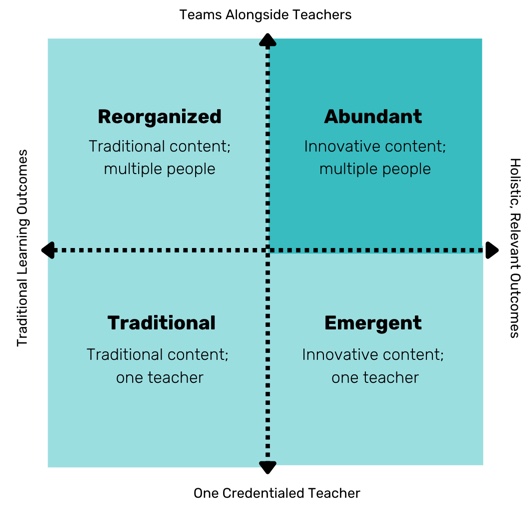

Through conversations with colleagues and peers, I’ve created a graphic to offer common language and invite collective learning:

Along the x-axis is what young people learn, from narrow academic outcomes measured by tests, quizzes, and essays to holistic, relevant outcomes measured through industry credentials, portfolios, performance assessments etc.

Along the y-axis is who facilitates the learning, from a single certified teacher in one classroom to a broadened team of educators, community members, and peer youth supporting student growth.

These four quadrants help surface usable lessons:

Traditional: Traditional content, one teacher

These schools deliver content in academic silos like math, science, and history and measure student progress using standardized assessments. A single certified educator works within a classroom for one class period or a full school day, and students move around as the bell rings. Students advance grade levels and graduate based on age and the number of classes they’ve successfully completed.

Reorganized: Traditional content, multiple people

These schools focus on core academics while expanding the team of people who support students. Some schools expand the reach of their best educators (using virtual platforms to reach more students) while apprentice teachers and/or community members serve as on-site assistants. Look at the non-profit National Education Equity Lab, which engages college professors to teach virtual credit-bearing courses to high schoolers, who then get support from first-generation college student advisors.

Emergent: Innovative content, one teacher

These schools expand what and how young people learn, while relying on a sole certified teacher to guide instruction. Educators design project-based units, young people solve contemporary problems through real-world experiences, or schools modify the design of the school week to expand learning outcomes. Look at Van Ness Elementary School, a District of Columbia public school centering a whole child approach to help young people manage trauma, stress, and conflict.

Abundant: Innovative content, multiple people

These schools offer learning on varied outcomes, ranging from on-the-job training to global citizenship to the development of learner agency and curiosity. This can take several forms: Elders connect science to local agricultural traditions. Industry professionals train students to complete career certifications. Librarians help young people develop research skills. Peers who have mastered content get credit and/or compensation to teach their classmates. International leaders offer virtual content and cross-cultural understanding. Look at Brooklyn STEAM Center, a New York City public high school offering five pathways: Construction Technology, Design & Engineering, Film & Media, Computer Science, and Culinary Arts & Management. Because the campus is in an industrial park, students spend part of the day at an internship, networking with professionals in their chosen field. Graduates leave with industry credentials in hand.

When we move toward this fourth quadrant, young people will be better prepared and excited to learn, schools will attract adults who can bring their unique expertise to bear, and our whole education system will be more dynamic and adaptable.

If we don’t shift our orientation now, I don’t know when we’re going to get another chance.

To be clear, I’d never suggest we deprioritize rigorous academics. Research proves that early literacy and middle grades math have an outsized impact on young people’s life outcomes. Instead, by sharing the responsibility of supporting a young person’s diverse learning needs across a team of people, we help educators focus on what they are uniquely positioned to do — and in turn, make the role more attractive and sustainable.

What I’m introducing here can and should work in concert with existing solutions for the staffing shortage, like significant increases in teacher pay, more flexibility and ownership in the teacher’s role, and reduced barriers to enter the profession. But these strategies alone are still too superficial to create the type of radically different learning we know our young people need and deserve.

I invite your partnership as we learn from existing schools and define a new path forward for both young people and adults.

This post is part of our New Pathways campaign sponsored by American Student Assistance® (ASA), Stand Together and the Walton Family Foundation.

Michelle Culver is the Founder of The Reinvention Lab powered by Teach For America.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.