Care: A Love Story

Key Points

-

We’ll all need care, we’ll all have the chance to provide care, and our systems alone are not enough.

-

Paul and Mari’s story has lessons for us all as we think about composing a future that makes possible the kind of care we need to heal and move forward.

By: Eric Tucker and Eva Dienel

It is not an understatement to say that the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will be with schools, with each of us, for a long time. As an educator, I have seen firsthand how it has affected the Brooklyn LAB school community. We have experienced collective trauma, and we’ll need time to recover and heal.

But we’ll also need something else: We’ll need each other. More specifically: We’ll need to care for each other.

This is not something that always comes easily in America. Our education and health systems are not set up for it, and even our culture encourages people in need to deal with issues themselves; it’s up to us and usually our immediate family to cope with hard times.

This approach doesn’t work for anyone. We deserve, indeed need, a better way.

This school year, I have been reflecting: How can we, as educators, create more space and provide more support for care within our school community? How can we best advance the struggle for human dignity?

I held these questions recently when I learned about the experience of a colleague and friend of our school community: Paul O’Neill, an education attorney and passionate advocate for students who learn and develop differently, and his wife, Margaret—Mari to the many who know and love her—who has dedicated her life to caring for others.

Paul and Mari’s story has lessons for us all as we think about composing a future that makes possible the kind of care we need to heal and move forward.

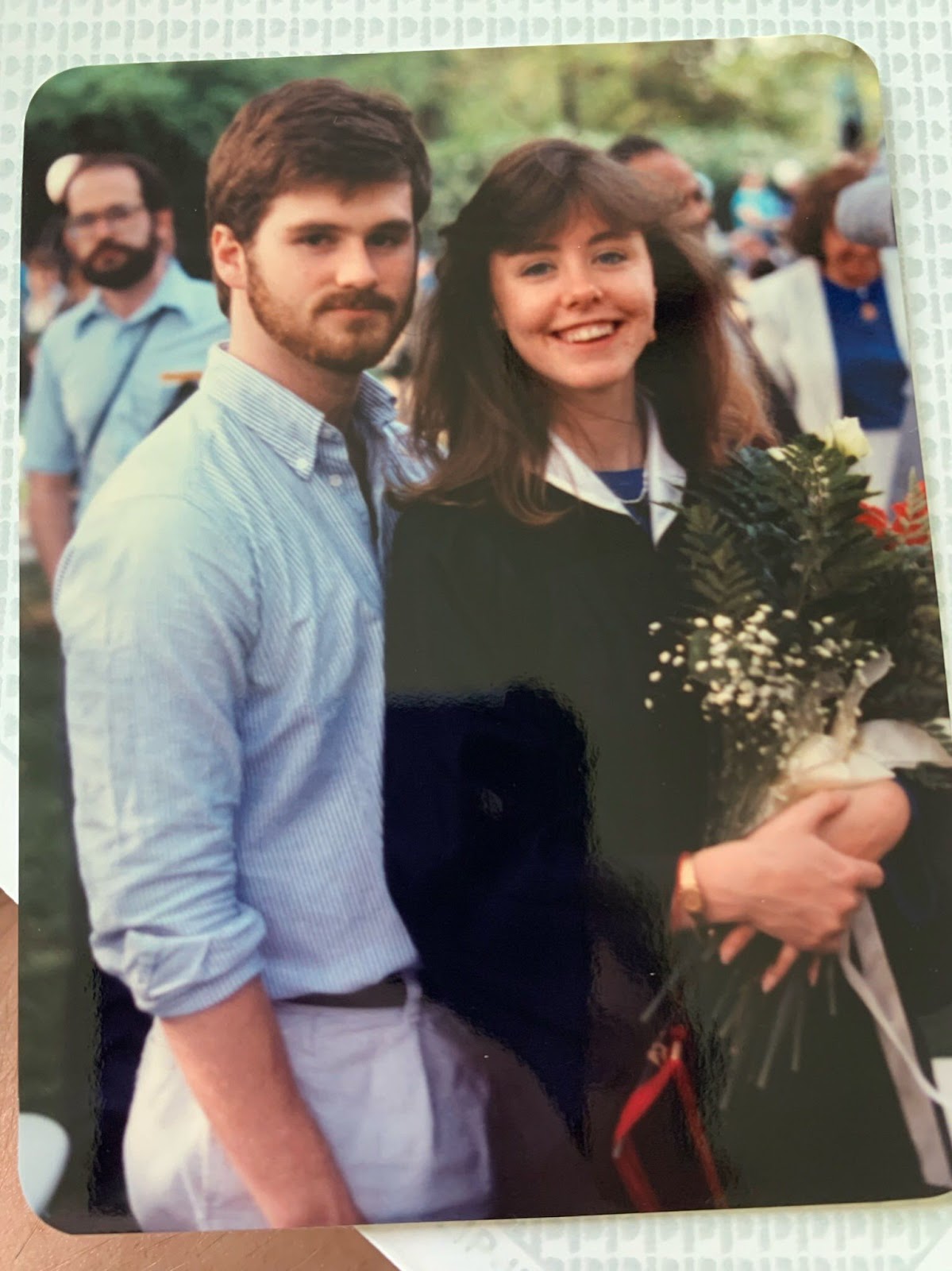

It begins as a love story. Paul and Mari met at 14 through a Catholic youth organization in New Jersey, where Mari and Paul’s brother were the leads in a local production of The Sound of Music. Mari had a crush on Paul’s brother, but when Mari and Paul graduated from high school and ended up at the same community college, they started dating. They were 17.

Over the next few years, they pursued their own paths in higher education, even as they remained together as a couple: Paul earned his bachelor’s from Oberlin, and Mari, always an altruistic person, began studying gerontology, later switching to elementary education.

They got married in 1989, and Mari took a job as a Catholic school teacher, later switching to HR, and then briefly enrolling in a master’s program at Teachers College. By the time Paul finished law school, they had their first of three children, and Mari decided to stay at home with the kids, while continuing volunteer work in her community. She joined the Glen Ridge Volunteer Ambulance Squad, first driving the rig and then taking on an unpaid administrative role to organize other volunteers. She volunteered for a hospice center, helping people through the last days, weeks, and months of their life. On Sunday mornings, she cooked for people in need, getting the whole family involved to make big dinners of chicken and rice.

For his part, Paul, who never got the support he needed in school as a student with learning disabilities and ADHD, was drawn to become an education advocate. After law school, he pursued his master’s in education and became an expert in special education law.

Family has always been at the center of Mari and Paul’s lives. They are close with their three children, who are all adults now. Twice a year, Mari’s extended family, who are spread across the country, come together for what they call “Farrell Week” after her family’s surname. During these times, they revel in each other’s company. And when anyone experiences hardship, they pull each other closer.

When the pandemic hit, Paul and Mari naturally thought about their family and community. They thought about their son, who’s in school for a public health degree and moonlights as an EMT. And they thought about their daughter, working long hours as a lawyer in Manhattan.

In February 2020, around the time New York’s first coronavirus patient began to feel ill, Mari noticed a prickly sensation on her tongue. She pushed the feeling aside, thinking maybe she’d eaten too much lemon. There were more pressing things to focus on.

Within our communities, we hold the power of care, even as our systems fail us.

Eric Tucker and Eva Dienel

As the pandemic spread and public life began shutting down, Mari and Paul stayed connected with their family and community through a social distance. They distributed handmade masks sewed by a neighbor, leaving a donation that went to charity. They dropped off groceries and Easter baskets on the curb at 7th Avenue and 16th Street for their daughter.

And Mari continued her work for the food pantry, doing her part to help the estimated 42 million Americans who experienced food insecurity during the pandemic. She got everybody involved, tugging them by the ear if necessary. When Mari heard that an older woman in their community needed help getting food, she bought provisions for the woman every time she and Paul shopped for family groceries.

As spring turned to summer, the tingling on Mari’s tongue spread, progressing through her mouth and throat, making it difficult to speak and swallow. At first, doctors thought Mari might have a condition called dystonia, which manifests with involuntary muscle contractions. By July, they settled on a more ominous diagnosis: She has Bulbar onset ALS, a form of the disease that debilitates the body much faster than limb onset ALS.

Mari’s diagnosis has been devastating, and also, ever the caretaker, her first response was to think about how it might affect others. How could she put them on a path to take better care of themselves, and set the family up to be OK without her?

Paul is juggling a lot. In anticipation of Mari’s needs as her disease progresses, he organized a move to his childhood home, which has a more accessible layout. They moved just after Hurricane Ida, and both their old house and new one flooded. In preparing for Mari’s care, Paul learned that in New Jersey, where they live, Medicaid benefits are more limited and financially ruinous to access than they are in New York, which is achingly close. They learned about the costs of the bed Mari might need, and the round-the-clock care, and how little of it is covered by insurance. Family and friends set up a GoFundMe, to help with the potentially catastrophic expenses and share supportive messages.

Despite their hardships, Paul points out that his family is fortunate. They have a home, access to healthcare, and a strong community. But as someone who has both lived and professional experience with disability, Paul has seen how often America’s systems fail vulnerable people. He described the “smallness and the meanness and the narrowness of the structure that we consider to be the standard.”

He’s right, and that standard needs to change.

Whenever we have leaned most heavily on Paul’s support at Brooklyn LAB, it’s been during a moment of vulnerability. My team and I go to Paul because we need his guidance on how best to meet the needs of a student or family whose needs have not yet been appropriately met.

No matter how intractable the situation, Paul responds with the kind of empathy, compassion, and commitment to human dignity that come from a place of deep care. He asks, “Who deserves less than everything we can do for them?” That question captures why we are proud to have Paul as a member of our wider school community.

Paul and Mari’s story shows us the best of who we are as people and the worst of who we are as a society: Within our communities, we hold the power of care, even as our systems fail us. We need people like Mari, who provide a community safety net to care for and love people when they are in a vulnerable place. We also need to secure our social safety nets, including in education, to meet people’s basic human needs.

During the darkest moments of this pandemic, one lesson has stuck: At some point, we’ll all need care, we’ll all have the chance to provide care, and our systems alone are not enough.

If you have been inspired by Paul and Mari’s story, please consider contributing to their GoFundMe or honoring Mari’s lifelong dedication to caring by supporting someone in need in your school community.

Eva Dienel is a journalist, writer, editor, and communications professional with more than 20 years of experience telling stories that matter—stories with an environmental, social, or human focus that engage people in making the world a better place. She is also the co-creator of the storytelling project The Life I Want, about a future of work that works for all.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.