Booker T. Washington: A Project-Based Learning Pioneer

In 1990, Harvard professor Joseph Featherstone wrote, “Educators often exist within a ‘United States of Amnesia,’ unaware of the history that precedes them and ignorant of past endeavors that closely mirrors what they hope to achieve in the present.” Few conversations exemplify this idea of “education amnesia” better than those around authentic experience, project-based learning, and the need to promote student agency. Promoted as innovative and transformational strategies to better prepare students for the demands of the 21st century, these ideas actually have their roots in the past.

Though many authors, policymakers, and pundits lament that the current education system was designed to meet the needs of an Industrial Era and thus no longer sufficient, much can be learned from the turn of the 20th century. As the nation recovered from the Civil War and wrestled with the economic, social, and racial tensions associated with the Reconstruction Era, the notion of industrial education began to take shape as a means to prepare students for the demands of a new economy. For example, in 1881, Booker T. Washington founded one of the most innovative educational institutions in the country: The Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute.

The Tuskegee Institute as a Model Project-Based School

A disciple of the famous Swiss education reformer, Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi, Washington believed that education best occurs when students learn in a progression from the familiar to the abstract; they use multiple modalities to actively explore content and ideas; and the learning experiences feel deeply personal. As such, he designed the Tuskegee Institute to equally value both academic theory and practical experience.

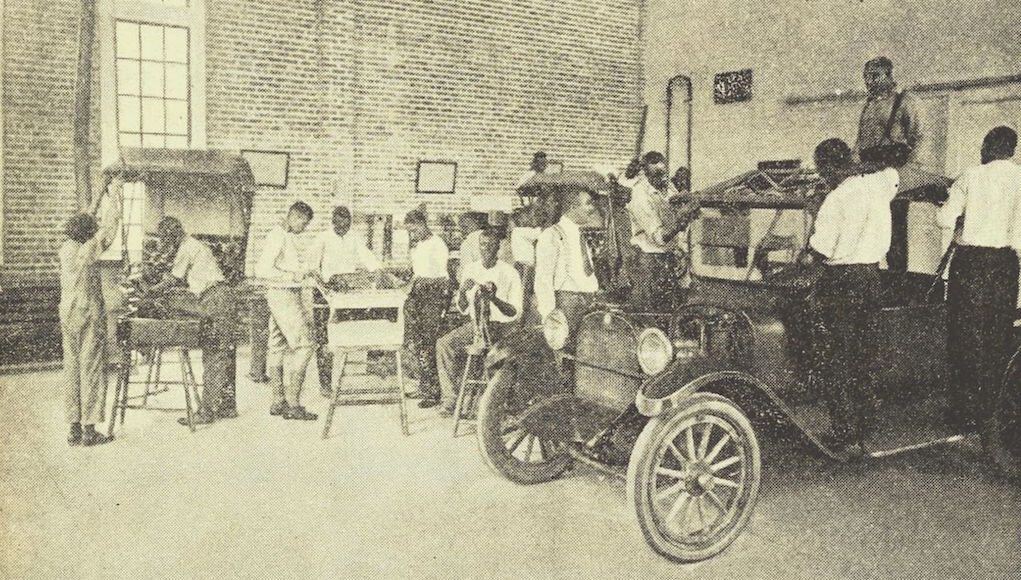

Decades ahead of more well-known Progressives such as John Dewey who advocated that education should prepare students for active participation in a democratic society, Washington thought that personal, lived experience should serve as the basis for education. To connect theoretical and abstract academic ideas with the students’ social and economic environments, he based education on real world versus ‘fake’ or contrived teacher-directed projects. In many ways, the Tuskegee Institute may exist as the first instance of a project-based learning school. Beginning with students participating in the physical construction of buildings and the farming of surrounding fields, theory classes such as math, grammar, and history immediately responded to the questions and challenges that students encountered in practice.

In one example, students identified the need for a new cement walkway between buildings. Immediately, the students encountered an array of challenges from measuring the length and width of the walk, to calculating the cost of materials, to determining the correct proportions of sand and rock to mix the concrete. The students identified the problems, sought out the solutions, and then built the final project—combining both vocational and academic skills. On another occasion, one of the teachers took her grammar class to observe a blacksmith’s shop. By making literal connections between abstract concepts such as subject and predicate with the physical motions of the blacksmith, the teacher found that her students learned the content more quickly and became more excited about the process of developing language skills.

Washington believed in a combination of intellectualism and pragmatism for his students such that they developed higher order thinking skills through intellectually demanding tasks and culturally relevant experience. When examined through the framework of High Quality Project Based Learning (HQPBL), his curriculum adhered to each of the tenets. Students completed intellectually challenging work in an authentic manner that was both meaningful and applicable to their lives. They collaborated to produce public products, managed themselves and their teams – which often included students from multiple grade levels, and engaged in active reflection to increase personal agency.

Industrial Education Ideals for 21st Century Innovation

Three ideals emerged from the Tuskegee Institute that could serve as exemplars for today’s schools. First, Booker T. Washington and his colleagues found value in teaching concepts and ideas that directly related to their students’ lived experiences. At the time, that included agriculture, construction, and engineering. However, teachers could use more culturally relevant approaches today and offer students the opportunity to leverage fields that range from computer science to e-commerce and marketing. Second, Washington firmly believed that students need the opportunity to experiment and create in order to learn. They should have a chance to wrestle with complex problems and collaborate on solutions – whether that be the construction of a building or the delivery of an oration. Finally, students at the Tuskegee Institute developed shared language, values, and norms through community partnerships and apprenticeships.

Booker T. Washington believed that all experiences could ultimately serve as the foundation for student education. However, in order to do so, the curriculum had to meet the immediate intellectual needs of the students as well as address the broader demands of society. Beyond academics, he felt that an industrial education should prepare students to be industrious, to have the tenacity to succeed in work and life within an increasingly urban and technological world. A sentiment often repeated by today’s education reformers who advocate that school should prepare students for lifelong learning. As Generals explained at the turn of the 21st century, Washington’s ideas and the curriculum of the Tuskegee Institute could serve as a model for addressing many modern educational challenges. The ideals of connecting content and curriculum to the needs of the learner; creating authentic, culturally relevant experiences; and directly connecting students to the broader community would ultimately create a 21st century education to the benefit of all students.

For more, see:

- Brain Research, Creativity and Project-Based Learning

- Project-Based Learning Connects Real World With Deep Impact

- Tools for Project-Based Learning: The Landscape Today

Stay in-the-know with innovations in learning by signing up for the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.