Show What You Know: The Shift to Competency

“G.P.A.s are worthless as a criteria for hiring, and test scores are worthless,” said Laszlo Bock, former head of HR at Google. “Google famously used to ask everyone for a transcript and G.P.A.s and test scores, but we don’t anymore, unless you’re just a few years out of school. We found that they don’t predict anything,” added Bock.

In the now famous 2013 interview with the New York Times, Bock signaled the beginning of the end of courses and credits as the primary measure of learning and the beginning of the show what you know era.

Professions (including law, real estate, and accounting) have long relied on test-based measured of readiness. Some professions have gone a step beyond to require demonstrated competence (e.g., doctors and pilots are required to pass tests, endure simulations, and perform in a variety of live settings).

In dynamic job categories including information technology (as Bock notes), hiring is increasingly based on demonstrated skills–a portfolio of referenced work– rather than transcripts and grades. Learning in these rapidly evolving fields is often online or blended, modular, and delivered in quick sprints in new formats like coding bootcamps or nanodegrees.

If the world is heading towards demonstrated competency over traditional pedigrees and there is a new opportunity to accelerate individual learning pathways, what does it mean for traditional education?

How would show what you know education work?

For a couple hundred years, we’ve been grouping children by birthdate and providing similar learning experiences to all of them. In the last 20 years, along with the addition of information technology, there have been efforts around the edges to modify this batch processing system with a bunch of tacked on services for younger kids and a patchwork quilt of courses for older kids.

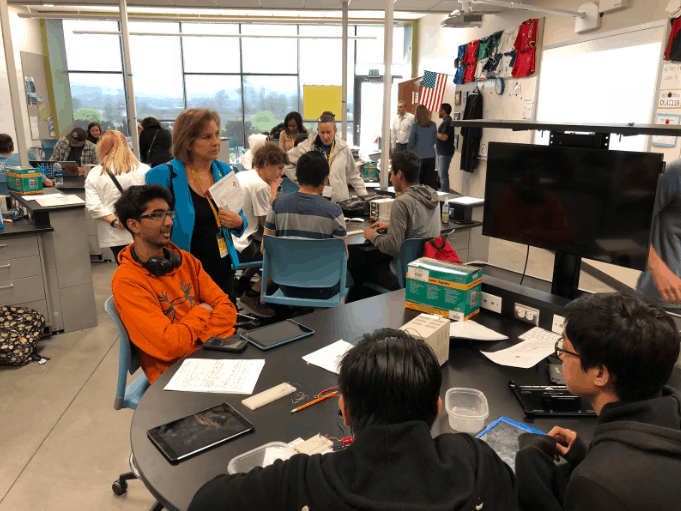

But finally, around the edges, we’re beginning to see education programs breaking free of lockstep progress–places where students can move on when ready and get more time and support when needed. It started in alternative high schools and moved into credit recovery courses. With better access to digital tools, there’s a new generation of schools that personalize learning and power individual progress models.

There are two big ideas behind the shift to competence in formal education. First, students should show what they know. It’s not about turning work in, earning points, or showing up to class, they should demonstrate in several ways that they have mastered important knowledge, skills, and abilities. Assessments in a competency-based system inform student learning as well as teacher judgments about concept mastery.

Second, students should progress when ready–after they’ve demonstrated mastery of important concepts that build a platform for future learning. For the system to promote equitable outcomes, it’s important that students receive timely, differentiated support based on their individual learning needs. The “move on when ready” commitment prevents passing learners along with a weak foundation which could prevent them from achieving higher level knowledge and skills.

On the list of risks to be avoided, it’s important that competencies not be a checklist of low level skills (e.g., I showed data analysis and integrity on that word problem so I can check them off the list). As leading competency advocate iNACOL says, “Competencies include explicit, measurable, transferable learning objectives that empower students.” Quality programs observe skill development in multiple contexts over time and may continue to provide feedback on success habits beyond initial mastery.

Bror Saxberg, Chief Learning Officer at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative said that “What’s most important for careers is the ability to decide and do: investigate, experiment, solve problems, compare, and communicate.”

Because experts unconsciously combine a lot of knowledge and skills to do things effortlessly, added Bror, they need to be diligent about picking out competencies for learners to master. He also noted that beyond the basics, competencies are often domain specific. Good writing in history isn’t the same as good writing in science. The same is true for mindsets–think grit in athletics vs algebra. As a result competency systems should include lots of practice in deciding and doing domain-specific practices to build expertise.

To illustrate the limitations of checklist competencies, Saxberg adds tips for learning concepts, processes, and principles:

- For facts, you do need to recall them, but in the context of “deciding and doing,” not isolated. If you don’t practice retrieving these facts in such a context, your mind does not develop the easy familiarity in context you need to bring them up “for real.”

- For concepts, learners need to practice classifying things among the concepts and generate examples of them, again within a “deciding and doing” context, since that’s how concepts help experts in solving problems.

- For processes, learners need to practice predicting what happens when inputs or conditions change in a process, and practice diagnosing what might be wrong given outputs or behaviors of processes, not merely “describe” the steps.

- For principles, learners need to practice applying these to solve new situations, or to predict what will happen, in domain-specific situations.

10 Elements of a Competency-Based System

‘Show what you know’ and ‘move on when ready’ sound simple but they change everything about how learning systems are designed. There are at least 10 design elements that must be considered:

- Competencies that in aggregate express a clear intellectual mission and in some detail what students should know and be able to do (see a summary of the 100 foundational concepts and habits of success at Minerva) of badges or credentials.

- Progress monitoring, historically thought of as grading, is a system of assessments that provides performance feedback to students to help them know if they’ve achieved mastery of a concept or skill.

- Grouping and scheduling systems—when, why and how groups are used when learning; not age cohorts as the dominant organizing principle.

- Achievement recognition that may include awarding badges or microcredentials to mark progress and replace metrics like class rank.

- Reporting progress to the outside world that still thinks in courses, credits, and grades. Initiatives like the Mastery Transcript Consortium will help. Clusters of microcredentials linked to job clusters called nanodegrees and specializations are another sign of progress.

- Content that supports self-directed and customized learning. There is more standards aligned open content but it doesn’t always include assessments that support competency-based progressions.

- Tools that facilitate competence-based challenges, collaboration, and scheduling. Most platforms and tools are still built for age cohorts.

- Teacher support, preparation and development for a dynamic environment with differentiated (i.e., different levels) and distributed (i.e., different locations) staffing.

- Evaluation systems that help to determine student learning and how experiences and adults are contributing.

- Community connections and supports for student success. Competency-based progress models are more equitable only if students that need it get more time and support.

Unfortunately, it’s tough to create and manage competency-based environments because there are not many models out there and the tool set is just not very good yet. But there are signs of progress where K-12 education is leading.

Where K-12 is leading the shift to competence

While education policy is still monopolized by grade levels and measures of time, show what you know practices are becoming more common in K-12 and higher education. There are five ways formal education is leading the shift to a show what you know world:

- Teacher selected microcredentials are rapidly replacing “sit and get” whole staff training in education. They give teachers a choice of what to work on and how to demonstrate progress.

- Credit recovery, acceleration and developmental courses: by recognizing prior learning and focusing on closing gaps, struggling students can often make up a year of progress in a few months.

- World language proficiency is inherently competence based.

- New career and technical pathways in robotics and advanced manufacturing incorporate industry certifications.

- Alternative postsecondary options including on demand courses, coding bootcamps, MOOCs, and skill certifications all point to flexible, modular, lifelong competency-based learning.

“Many districts are making the transition to competency-based education because they know that they can’t help all their students reach career and college readiness without greater personalization,” notes CompetencyWorks, a project of iNACOL.

Competency-based school models take advantage of new tools and strategies to enable students to learn at their own pace, any time and everywhere. The shift from marking time to ‘show what you know’ and ‘move on when ready’ will take a generation to become widespread but it has the potential to better prepare more young people for the innovation economy.

For more see:

- Model Schools, Districts, Networks and States for Competency-Based Ed

- 12 Onramps for Personalized and Competency-based Learning

- Progress on Proficiency-Based Education in New England

This post was originally published on Forbes.

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.