Creating Coherence: Central Office to Teacher Teams and Their Students

Teaching is hard enough, so it’s frustrating when schedules, systems and policies get in the way. Doug Knecht is trying to change that by promoting coherent education systems where everything works together to support teachers and students.

Knecht directs the Bank Street Education Center, an extension of the well-regarded New York education college.

The process starts “by putting students in the center,” said Knecht. With a focus on the intersections of child development and adult learning, the Education Center helps school systems build “a coherent throughline from the central office and pedagogical supervisors to teacher teams and their students.”

Knecht studied ecology and evolutionary biology at Princeton, which grounded him in a view of complex systems. The power of the environment to shape development left a big impression. When an organism was well aligned with its ecosystem, there was no stopping it.

As a science teacher, Knecht’s first assignment was at a well-regarded New Jersey high school that sent lots of mixed messages. While talking about equity, the highly tracked school skewed resources toward higher performing kids, such as additional lab periods, and wordlessly mentored new teachers to lower their expectations for students from the poor side of town. Despite many committed staff members, the school seemed to be working against itself, undermining its mission. It felt incoherent.

Then, as a founding teacher at Humanities Preparatory Academy in New York City, Knecht had first-hand experience in designing a coherent school. Launched in 1997 with support from New Visions for Public Schools, the Humanities Prep team embraced a mission “to provide a philosophical and practical education for all students, an education that features creativity and inquiry, encourages habitual reading and productivity, as well as self-reflection and original thought.”

Humanities Prep purposefully integrated off-track high schoolers, as a transfer school, with incoming ninth graders, as in a traditional setting. Other intentional structural designs–such as student choice in programming, daily advisories, weekly town meetings and a restorative justice through fairness committee–coherently imbued the community with “the values of democracy: mutual respect, cooperation, empathy, the love of humankind, justice for all and service to the world” (twenty years later, the mission and vision seem more important than ever). The small diverse Chelsea high school also features small heterogeneously grouped classes, a student-centered pedagogy, deep investigations and self-reflection.

The opportunity to create a coherent new school with assistance from several valuable partners “informed my views greatly,” said Knecht. Coherent schools align culture, structure and instruction, said Knecht. This creates role and goal clarity–for teachers and students.

When, for example, you are striving for a community that promotes debate using evidence to get to a greater truth, there must be alignment of the cultural norms (respectful conflict is welcome), structures (long enough class periods to research and perform debate projects) and instruction (teacher practices that ensure all students support claims and/or counterclaims with evidence and reflect on their shifting beliefs). Without coherence around these pieces, a school will be much less effective at achieving its lofty goals with all learners.

Importantly, Humanities Prep uses performance-based assessment tasks as graduation requirements. The school is one around 50 members of the New York Performance Standards Consortium that share a rich performance assessment system. It was approved as an alternative to state tests by the Board of Regents in 1995 and reaffirmed in 2008 when additional schools were added (see feature).

The assessment system has created a blueprint for coherent schooling that reaches all students, and the Consortium has acted as a network for learning and development across the participating schools – for students, teachers and school leaders as well as at the district and state levels.

As recent policies and initiatives, from teacher evaluation to blended and personalize learning, make schools more complicated places, Knecht thinks support networks are important for creating and maintaining coherence. “Given the demands on educators these days,” he said, “school communities need supportive ecosystems with feedback, externally as well as internally, that point out how well their culture, structures and instruction are aligned to their mission and values.”

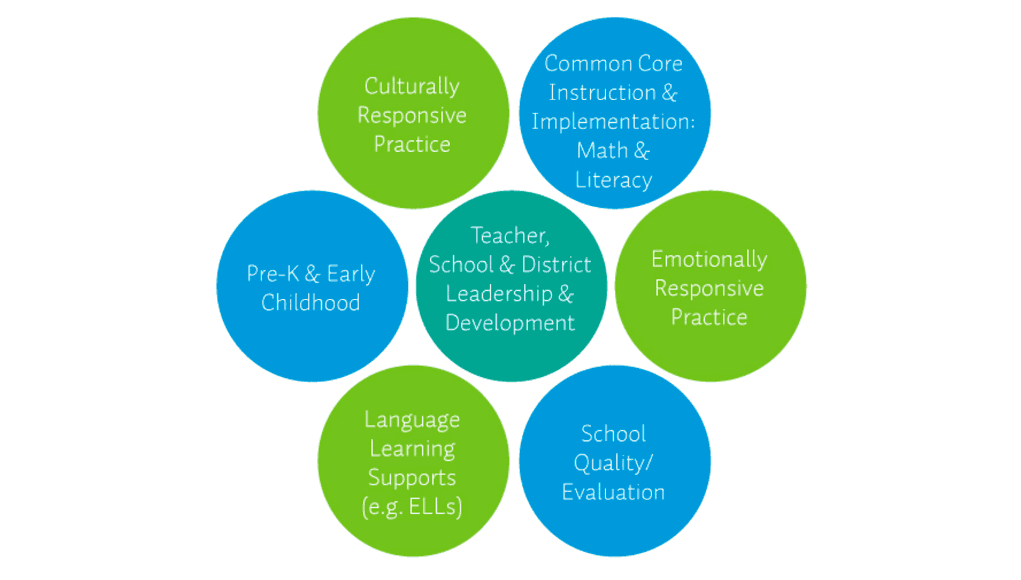

With support from the Gates Foundation, Bank Street Education Center is working with four urban New York districts to see if the districts themselves can provide these kinds of supportive, network-like conditions. Given the frequent shifts in district leadership that can create system-level incoherence, Knecht sees external partners like the Education Center (and the networks they lead) as supports to sustain coherence across changing administrations.

For more, see:

- How Can We Build Trust Within Our Education System?

- System Connectors and Shapers in Education Transformations

- Generic vs Coherent Teacher Prep

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.