Teachers Should Have the Option of Working in Teacher-Led Schools

In most professions, practicing in a professional partnership is an option. It’s common in law, medicine, accounting, and real estate–not so much in education. It should be an option available to all teachers.

The first national meeting of teachers interested and active in teacher led school was held in Minneapolis in November 6-7. About 220 teachers, from 23 states, paid their way here to spend the weekend talking about how to get into this arrangement and how to operate it once they have it.

About half were from the charter sector, the other half from district schools. Ted Kolderie, an advocate for teacher-led schools said, “This is an idea that washes out that sector-difference; a nice case we think of an innovation in the chartered sector moving laterally, through the teachers, into the district sector.”

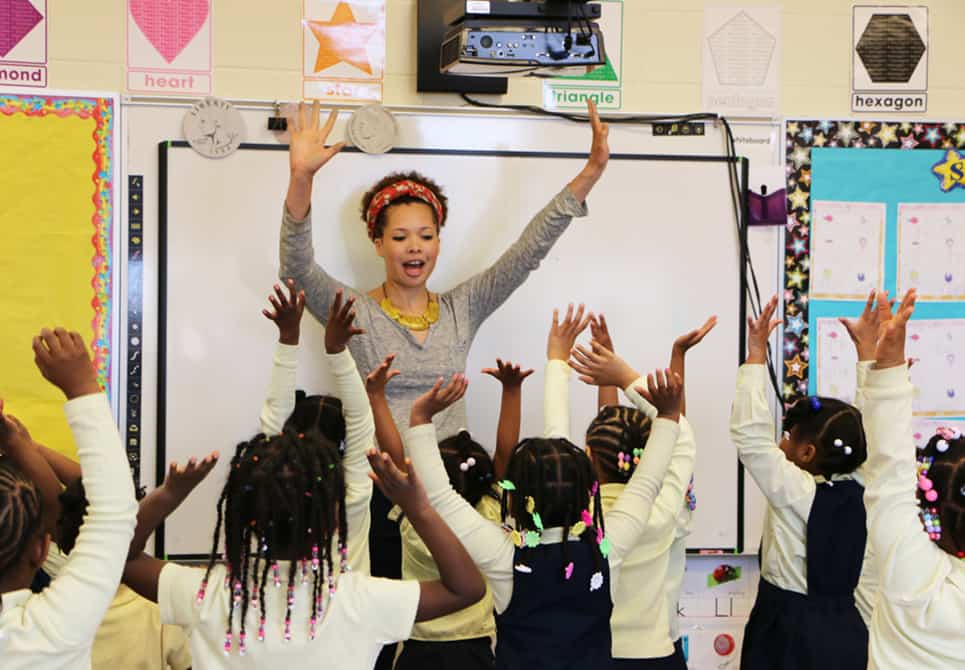

Kolderie, founder of the think tank Education Evolving, told me about teacher-led schools 2000. He convinced me to visit Minnesota New Country School (featured image) where teachers had created an innovative project-based and fully individualized school — and they were in charge. MNCS teachers had formed a co-op and applied for a charter and operated with full autonomy. It was easily the coolest school I had visited.

The idea of teacher-led schools was outlined in Free to Teach, Joe Nathan’s 1983 book. Among other things, this book urged that teachers should be given the right to create new options, open to all kind of kids, from which families could choose. Nathan’s book helped shape a 1985 NGA report, “Time for Results” which, with leadership from Governors Alexander, Clinton, and Riley, gave rise to the expansion of public school options (as well as standards-based reforms).

Trusting Teacher With School Success, a book by Kim Farris-Berg and Edward Dirkswager, is an in depth look at teacher-led schools–why and how they work and the key ingredients of success. Every teacher should have the opportunity to work in a teacher-led environment and should read this book to find out why.

The central question of the book is “what would teachers do if they had the autonomy not just to make classroom decisions, but to collectively–with their colleagues–make the decisions influencing whole school success?”

The authors outline 10 key autonomies:

- Selecting colleagues

- Transferring and/or terminating colleagues

- Evaluating colleagues

- Setting staff pattern (including size of staff and the allocation of personnel to teaching and/or other positions)

- Selecting and deselecting leaders

- Determining budget

- Determining salaries and benefits

- Determining learning program and learning materials (including teaching methods, curriculum, and levels of technology); and

- Setting the schedule (classes, school hours, length of school year).

- Setting school level policies (including discipline and homework protocol).

The authors identified and studied 11 schools that had at least six of the autonomies and had been operation for at least three years. The 11 schools showed high correlation with the attributes of high performing organizations and shared eight practices:

- Share purpose , which always focuses on students as individuals, and use it as the basis of decisions aimed at school improvement.

- Participate in collaboration and leadership for the good of the whole school , not just a classroom.

- Encourage colleagues and students to be active, ongoing learners in an effort to nurture everyone’s engagement and motivation.

- Develop or adopt learning programs that individualize student learning.

- Address social and discipline problems as part of student learning.

- Broaden the definition and scope of student achievement and assessment .

- Encourage teacher improvement using 360 degree, peer- and self-evaluation methods as well as peer coaching and mentoring.

- Make budget trade-offs to meet the needs of the students they serve.

The book refers to “autonomous teachers,” which is slightly misleading, these are partially autonomous schools that are teacher-led. The semantics matter because, having visited most of these schools I find teachers in these environments highly accountable to each other, students and parents. They are actually less autonomous than teachers in traditional schools, but they operate as owners, which makes all the difference in the world.

We’ve had a high level of nearly autonomous individual practice in most schools for decades and it doesn’t work very well. In some respect, teachers in the studied schools have less autonomy than what is considered traditional. Teachers in the studied schools are bound together in an accountable collective with a shared mission with a great deal of responsibility to each other and their students.

The key ingredient, that I would have emphasized more, is the performance contract that creates conditions of partial-autonomy and describes the relationship with the authorizer.

The new push for better teacher evaluation may create problems for some of these schools — another reason the performance contract is so important.

The success of these schools may start with the governance model — teacher led charters — but they are also small, focused, mission-driven, student-centered, and (for the most part) competency-based. They say it’s not about small, but it would be hard to make this work in a building with 100 teachers.

There’s little mention of cooperatives in the book but that’s how the original schools were formed and I find it both descriptive and a useful organizational structure. As education shifts from a place to a bundle of personal digital learning services, it creates opportunities for teachers to ban together to provide online and blended services, for example: an online AP teacher co-op, an online speech therapy co-op, a foreign language co-op.

Another reason for exploring co-ops is that the 11 case studies are hand-crafted schools (as Deborah Meier would say, recreated daily in a meeting of the faculty) and it begs the question of scalability. Co-ops strike me as scalable structures for supporting teacher-led schools.

Promising Trends

One of the exciting things about the shift to personal digital learning is the explosion of career options for learning professionals — more school models, more learning services, and more ways to contribute. In every other profession, there is a choice of working for a government services, a large private practice, a professional partnership, or as a sole practitioner. Teachers should have the same options.

Kolderie thinks the trend toward personalizing learning will be helpful “because no one knows the students as individuals like teachers.”

The Teacher-Powered Schools Initiative was launched in May 2014 with the goals of highlighting the successes of the more than 90 teacher-powered schools across the country, and inspiring other teachers to either take charge in their schools or design and run new schools.

The growth of micro-schools, both private and public, may be the most powerful force advancing teacher-led schools. Most micro-schools are 2-4 teachers working with 40 to 100 students. Most are highly personalized and developed in networks that share a common platform. (Want to learn more? See 4.0 Schools Tiny Fellowship.)

Teacher-led environments aren’t for everyone. There’s a lot of responsibility and hard work that goes with being an ‘owner’, but it does reframe accountability as a gift, a promise, and a practice.

Teacher-led schools are a great idea. As the authors admit, they are not for everyone. But given the advantages, there should be thousands not dozens.

This blog is an update of a November 2012 post.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.