Michael Stone & Kristen Burrus on Bridging Learning to Careers

Key Points

-

Fab labs provide a tangible way to integrate project-based learning, credentialing, and essential skill-building, offering students functional solutions to real-world problems.

-

Connecting education to workforce needs through partnerships with local businesses ensures that learning is purposeful and directly impacts students’ futures.

On this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, Nate McClennen is joined by Kristen Burrus and Michael Stone from Chattanooga to discuss how fab labs and innovative learning ecosystems are transforming STEM education. They explore how STEM School Chattanooga and the Volkswagen eLab Network are integrating project-based learning, credentialing, and essential skill-building to create meaningful pathways for students. Learn how these efforts are bridging the gap between education and workforce readiness, offering students functional solutions to real-world challenges.

Outline

- (00:00) Introduction and Podcast Overview

- (03:16) Memorable Learning Experiences

- (07:19) Chattanooga’s STEM School Journey

- (19:17) Leveraging Labs for Essential Skills

- (20:34) Certification Process and Success Stories

- (25:37) Building Fab Folio: From Google Forms to AI Integration

- (29:27) Impact and Future of Fab Folio

Introduction and Podcast Overview

Nate McClennen: Welcome, everybody. You’re listening to the Getting Smart podcast, and I am Nate McClennen. Super excited for our guests today. Over the last decade at Getting Smart, we’ve found many examples of innovative systems. That’s what we do—we look for interesting work that impacts student outcomes, increases student belonging, and helps students advance toward higher education or careers.

We get excited when we find new sites doing interesting work that pushes the transformative edges of the framework we use. As a reminder to listeners, we think about community vision as a really important part of our framework. We think about defining broader outcomes—not just standards, but competencies and durable skills that young people need to succeed in higher education and/or careers.

We also think about the learning model—how those outcomes are met through innovative learning models, whether it’s project-based learning, STEM labs, work-based learning, or something else. We think about signals—how learning is communicated to the world outside of K-12. Finally, we consider how learning sits within the larger learning ecosystem of a community. We know that learning happens in schools and outside of schools, but how do we create a broader learning ecosystem? These five elements—community vision, outcomes, learning models, signals, and learning ecosystems—are part of our framework.

On the outcomes side, we know that competency evaluation is pretty rare. Even if portraits of graduates exist, not many schools actually take that portrait of a graduate and move it into an evaluation system.

We’re curious when we find something like this, and today’s example has done that. In terms of learning ecosystems, we’re interested in how communities, regional efforts, and networks help facilitate better learning experiences for young people. We’ll hear a little bit about that today.

Finally, badging and credentialing are becoming more common signals on transcripts, with states like Indiana and Ohio increasing credential requirements for graduation. However, we still see many traditional transcripts that don’t allow young people to indicate what they’re able to do and the skills they’ve acquired through their school experiences. We’ll see some of that today as well.

Given this, we’re always searching for interesting stories. In April, I was at ASU+GSV in San Diego and wandered into the back of a presentation about halfway through. Two individuals were there who are on the podcast today, and they were talking about how to badge and credential, how to do fab labs, and how to credential in STEM systems, among other things. I met Kristen Burrus and Michael Stone from Chattanooga, and I’m super excited to have them on the podcast today.

Kristen is the program manager at the nation’s first K-14 Digital Fabrication Center and an educator at STEM School Chattanooga, which sounds like a really interesting school. I’m excited to learn more. Michael is the VP of Innovative Learning at the Public Education Foundation of Chattanooga’s Innovation Hub. Both are deeply immersed in advancing broader outcomes, better learning models, and expanded learning ecosystems in their area.

Welcome, happy first day of school (because I think it’s the first day of school), and thanks for being on the podcast.

Michael Stone: Thank you. Thanks.

Memorable Learning Experiences

Nate McClennen: All right, I’m going to start with my favorite question. Going back down memory lane, what was one of your most memorable learning experiences in K-12? By memorable, I mean highest engagement and strongest learning.

Kristen Burrus: Okay, so what’s not memorable is whether I was in ninth or 10th grade—I think probably 10th because I had the same English teacher for a couple of years in a row, so that’s why it gets confusing. But in my English class, we read The Canterbury Tales, and my teacher gave us all a story that we were to retell. We got to do the whole thing—we costumed, we had props, and then we retold the story for everyone in the class. I don’t remember ever laughing so hard—in a good way. It was hilarious because you never knew when she was going to call on you. We had to dress up for class for like four days in a row in high school. Anyway, it was great. It made me really care about the other people’s stories because they got to be creative. The Canterbury Tales is pretty interesting and a little bawdy for 10th grade too, so that was pretty fun. That was probably my best memory of a project or assignment in high school.

Michael Stone: Where my mind went immediately was fourth grade. Mrs. Hall was an amazing teacher at a little school in Orlando, Florida. She had us do a project—I don’t remember the exact context, but I remember what we built. We had to design a trifold poster while studying biomes and native species. We were assigned a biome and had to include facts and tidbits about different species in that biome.

I worked on the project with my mom. She was genuinely helpful—she didn’t do the project, but she helped. We stumbled into a library book with an idea to make it look like the creatures were coming off the poster using folded foam board. We printed, laminated, and mounted them so they would wiggle. The deep learning piece—I’m sure I learned about animals and biomes—but the part I haven’t forgotten is watching Mrs. Hall coach her student teacher on how to engage students. I remember thinking, “I don’t know what you have to do to teach teachers, but I’d love to do that.” Lo and behold, 30 years later, that’s what I do—work alongside great teachers and help them dream up new ways to teach. It left a huge imprint on me.

Nate McClennen: I think you might be one of the few people in the country who, as a fourth grader, knew you wanted to teach teachers. It’s one thing to be a teacher, but to teach teachers—that’s pretty amazing. Super helpful. Kristen, your memory jogged mine. I remember a ninth or 10th-grade biology project where we had to do something on mitosis and meiosis. One of my classmates had an early camcorder, and we dressed up as parts of the cell, replicating and running around outside while filming. I think we were mostly engaged with the video camera, but mitosis and meiosis are very sticky for me because of that activity.

Okay, so we know these are all deeper learning experiences. This is about project-based learning and creating experiences that are more interesting and challenging. You’ve come a long way from what we’ve described, and what you’ve built in Chattanooga is pretty complex, awesome, and high impact.

Chattanooga’s STEM School Journey

Nate McClennen: Because it’s fairly complicated, I want to prompt you both to explain what you do and what you’ve built, along with others, in whatever way you want. This could be a tag team—one person starts, the other continues—but help our listeners understand. I’ll ask questions along the way if I don’t understand.

Michael Stone: Okay, I think we’ll try to be brief and give you the high-level overview, but please interject with questions. For us, the story starts back in 2012 with Race to the Top. STEM School Chattanooga, where we’re sitting now, was started as one of a handful of platform schools across the country. It’s a public school, but we’d probably call it a magnet school if it had opened 10 years earlier. It’s accessible to kids all over the district, and they’ve done a great job making it equitable and representative of the whole district. It’s not selective in its process—grades 9-12, drawing from 23 middle schools.

When Tony Donen was starting the school, he was given a month to plan. The charge was to do PBL (project-based learning). He asked, “Do you mean project- or problem-based?” There were crickets, and someone finally said, “What do you want to do?” Over the years, they opened as a wall-to-wall PBL school, adding one grade at a time. By their second year, they were humming along with a small school doing wild, innovative work.

By their second year, they were really humming along with this small school doing wild, innovative work. They were partnering with businesses around their PBL units. Dr. Tony Donen, the principal, and Jim David, the assistant principal at the time (now the principal), sat together at the end of that second year and said, “Our kids are doing incredible work, but the PBL units are always ending with a duct tape and cardboard model and a slide deck.” Tony’s undergraduate degree is in systems engineering, so he knew the value of iterative work and continuous improvement. However, he recognized that the students weren’t getting the opportunity to build functional solutions to authentic problems.

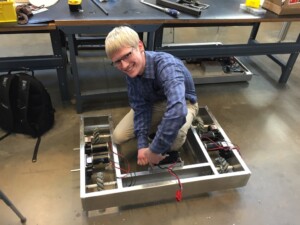

They stumbled into the Fab Lab model from MIT and the Fab Foundation. They were fascinated by the idea of a standardized system where, if you could dream it, you could build it. This idea of Neil Gershenfeld’s “How to Make (Almost) Anything” course really resonated with them. Two years later, I had the opportunity to join the school. I had no training in Fab Labs and was very honest about that. My undergraduate degree was in computer science, so I felt comfortable with IT, but I didn’t own a power tool and paid people to change my oil. Routers and 3D printers were not in my wheelhouse.

In my interview, Tony explained what a Fab Lab was, and I said, “I don’t do that kind of stuff. I’d love to work here, but I don’t think I’m qualified.” He asked, “Would you be willing to model the process you go through to learn how to use those tools?” I said yes, but I’d have to do a lot of experimentation. He replied, “We want a teacher who’s not an expert in everything but who can model how to be an expert learner.”

Two years later, we had a Fab Lab up and running. The intent was built around the STEM school’s mission statement: to develop students who are innovators, collaborators, and critical thinkers. I’ll never forget that because it’s the very ethos of the school. It’s not just words on a wall—it’s the foundation of every decision they make. When we brought the Fab Lab in, it wasn’t about the tools; it was about the learning model. The question was, “When students have access to this technology, can we teach them two critical things?”

First, could we teach them to be confident enough to learn the technology right when they needed it? This meant giving them just enough information about 3D modeling, CNC design, mechanics, or coding so that they could bring an idea to life. Second, had they developed what we now call essential skills? These include resilience, collaboration, innovation, and critical thinking.

This work led to a significant investment from Volkswagen in 2017. They made a $1 million investment, which we grew into about $3 million in initial seed funding. Since then, we’ve taken the learning model from STEM School Chattanooga and synthesized it into a packageable experience that we can bring to schools across our community. We’ve now opened 55 Fab Labs in schools from K-12 across our community. Our school system has about 80 schools, so roughly two-thirds of our schools now have fully integrated Fab Labs. These labs use the same learning model as the STEM school, leveraging the Fab Lab as a Trojan horse to bring students into experiences that elevate their opportunity to develop critical skills and technical fluencies.

As this was happening, Kristen joined the team. She was one of our first Volkswagen eLab specialists and left a non-technical field to do this work because she was passionate about it.

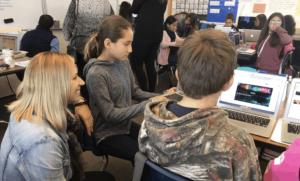

Kristen Burrus: I think it’s funny that both of your stories earlier were about science because that’s what I taught for almost 18 years, yet that wasn’t my example. I taught biology, anatomy and physiology, and seventh-grade science for years. I always loved engaging students in class.

In 2017, when we had the opportunity to write a proposal to apply for one of these Volkswagen eLabs, I was at a K-12 magnet school in Hamilton County. We got the proposal accepted and started our lab that year. It was absolutely fantastic. I saw how my students reacted to having these opportunities, which were so foreign to them but applicable to any content lesson. I got to work with kindergartners on an elevated egg drop based on Humpty Dumpty and do all these really cool PBLs with students across all content areas and ages.

When they were starting the Global Center for Digital Innovation (GCDI)—that’s why we call it the GCDI; it’s a mouthful—I was excited. It was probably the only thing that could pull me away from the school I was at before. I decided it would be a really neat opportunity to come on board and be part of the STEM school.

The STEM school and the GCDI are part of Chattanooga State Community College. We’re on a college campus, which adds to the experience for STEM school students. Our 11th and 12th graders take college classes, sometimes more than high school classes. It’s a very fluid experience for them.

Nate McClennen: Are you still teaching at the STEM school, or how does your job look now?

Kristen Burrus: My job includes two planned classes every morning with STEM school students. I teach ninth and 10th graders in a class called Tech Time. According to the state of Tennessee, it’s called STEM I, but we call it Tech Time. After about 12:15, my schedule is open for collaboration with other STEM school teachers. We’re literally next door, so I have a lot of STEM school classes come to the GCDI for collaborative projects. The high school also has its own Fab Lab.

Michael Stone: That model is symbolic of what we see across the Volkswagen eLab network. Kristen’s lab schedule is hybrid—she has scheduled classes and unscheduled time to serve as a PBL coach and co-facilitator. She helps teachers integrate the lab into their lessons, whether it’s history, science, or another subject. For example, she might help a history teacher create a project on the civil rights era using digital fabrication.

Michael Stone: For example, Kristen might sit with a history teacher who says, “I don’t know how U.S. history and digital fabrication connect.” She’ll ask, “What unit are you teaching?” If the teacher says, “We’re teaching about the civil rights era,” Kristen will brainstorm with them to co-plan and create engaging, tangible ways to repackage the student experience. This collaboration is symbolic of what we see across the Volkswagen eLab network.

We call Kristen’s lab schedule a hybrid model. She has scheduled classes where students come in as part of their regular schedule, but she also has unscheduled time to serve as a PBL coach and co-facilitator. This allows her to help other teachers integrate the lab into their lessons, whether it’s history, science, or another subject. This model is emblematic of the network’s approach.

Leveraging Labs for Essential Skills

Nate McClennen: So, going back to the network—the Volkswagen eLab network—55 schools of the approximately 80 in the district. How do they interact? Do they come together? Are there convenings? How do they amplify each other? What does that look like?

Michael Stone: That’s where my role with the Public Education Foundation and our community partners, like Volkswagen, has been helpful. The school district helps support the network, but by running this through a local nonprofit, we’ve been able to provide additional support. We convene the entire network multiple times a year. When we’re opening new labs, we provide a very scaffolded, explicit three years of professional development for the teachers and school leadership teams.

We’ve also built out a certification process that helps us assess and elevate the effectiveness of the labs. Initially, when we had eight labs, it was easy to keep our finger on the pulse. But as we grew over the last 10 years, we saw stratification—some labs were highly effective, while others weren’t quite reaching that mark. We needed a way to define and measure success.

We now certify labs across three levels: emerging, established, and leading. The progression moves from ensuring the lab is functional and accessible to students (emerging), to having a clear plan for developing essential and technical skills (established), to using the lab as an incubator for innovation and collaboration that impacts the entire school (leading).

For example, at Red Bank Elementary School, a small community school, they’ve gone through this journey. When we certified them at the leading level, it was a rigorous process. We spent four hours onsite observing their work. We looked for evidence that students had embraced essential skills not just in the lab but across all classrooms. For instance, we saw third graders in a reading circle using the same collaboration language they had been coached on in the lab. It was amazing to see how the lab’s impact extended beyond its walls.

Shorts Content

Certification Process and Success Stories

Michael Stone: The certification process has helped us identify and replicate best practices. Schools that achieve the leading level have a clear progression for developing skills across grade levels. For example, at the STEM school, they’ve defined what collaboration looks like for freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors. As freshmen, students focus on collaboration through the lens of diverse communication—working with people who have different backgrounds and personalities. As sophomores, they focus on collaboration through the lens of peer accountability—what to do when a team member isn’t pulling their weight.

However, they realized they weren’t giving students consistent feedback on these skills. Kristen piloted a system to document and assess students’ progress. This led to the development of Fab Folio, an app designed to give students clear feedback and a way to document evidence of their skills.

Building Fab Folio: From Google Forms to AI Integration

Kristen Burrus: When I started, part of my job was to help document what students were doing, specifically their technical skills progression. We started with a Google Form where students could document their proficiency in using tools like 3D printers. They had to meet specific criteria and upload evidence, like photos or videos. I managed all this data in a massive spreadsheet.

The next iteration was a Canvas course, which allowed me to provide written feedback. However, it was still cumbersome. Around this time, Michael and the team started developing Fab Folio, an app that would streamline this process.

Michael Stone: Fab Folio allows students to document evidence of their skills—whether it’s a text, video, photo, or CAD file—and receive real-time feedback. We recently integrated AI to provide immediate formative feedback, which has been a game changer. The app also maps clusters of skills to industry certifications, helping students see how their work aligns with workforce readiness.

For example, we worked with local employers like Blue Cross Blue Shield, Volkswagen, and Legacybox to identify the skills they value most. Each company selected a mix of technical and essential skills, and we created career clusters in Fab Folio. When students complete a cluster, they receive tangible incentives, like priority consideration for internships or jobs.

Impact and Future of Fab Folio

Michael Stone: This approach has had two major impacts. First, it’s closing the gap between education and workforce readiness. Second, it’s elevating the importance of essential skills in schools. Principals and district leaders are now asking how they can align their programs with the skills employers value most.

We’ve also realized that Fab Folio is a powerful data collection tool. It provides insights into students’ development of essential and technical skills, which is data we’ve never had before. This is just the beginning, and we’re excited to see where it leads.

Kristen Burrus: One of our goals is to create a Fab Folio skill transcript that students can attach to college or job applications. This would allow them to showcase their skills and provide concrete examples during interviews.

Nate McClennen: What is the biggest thing you’ve learned as a learner in this process?

Kristen Burrus: I’ve learned so much about what I’m capable of, especially with technology. I’ve also learned how to engage students without relying on grades. My class doesn’t have a grade associated with it, but over 90% of students achieve everything I ask of them because they’re motivated by the work itself.

Michael Stone: This work has changed my career and my outlook on education. I’m most excited about creating systems that empower teachers to be artisans and craftspeople. When we position teachers to facilitate rich learning experiences, we help students discover their unique interests and aptitudes. There’s nothing more empowering than that.

Nate McClennen: Thank you both. This has been an incredible conversation. I’m sure our listeners will be inspired by your work. We’ll include contact information and resources in the show notes. Happy first day of school!

Guest Bio

Michael Stone

ichael Stone is an experienced educator with a passion for teacher and leadership development. He currently serves as the Director of Innovative Learning for the Public Education Foundation in Chattanooga, TN, and is the Cofounder of devX PD, a national teacher and educational leadership professional development company. Blending his technology expertise with a passion and talent for effectively educating students and adults, he has become a national leader in instructional technology integration and professional development.

Michael spent the early part of his career working in Information Technology. However, his passion for education pulled him back to the classroom in 2006 when he began teaching Physics and other sciences at a private, parochial school in Tennessee (Hamilton Heights Christian Academy). After receiving a Masters of Arts in Instructional Leadership in 2008, Michael moved to public school where he spent five years as an advanced mathematics and computer science teacher. In 2014, he became the Project Based Learning (PBL) Manager and Fabrication Laboratory (FabLab) Director at STEM School Chattanooga. He served in this role until moving his family to Washington DC where he worked to support NSF’s efforts to broaden the scope of rigorous computer science education in the nation.

Kristin Burrus

Kristin Burrus has 22 years of experience in education. From 2017 to 2019, as a Fab Lab Specialist in a K-12 public magnet school, she developed and facilitated problem-based learning and design thinking units for elementary, middle, and high school students integrating digital fabrication into content classes. In August 2019, she became the Digital Fabrication Ecosystem Lead at STEM School Chattanooga, providing professional development and support for digital fabrication teachers in the district. Beginning March 2021, Kristin will be the lead teacher in the Global Center for Digital Innovation (GCDI), the first K-14 educational Fab Lab in the Nation. A collaboration between Hamilton County Schools and Chattanooga State Community College, the GCDI will be an anchor for the local Digital Fabrication Ecosystem of ideation (entrepreneurship), creation (digital fabrication), and production (manufacturing). The GCDI will provide classes, workshops, and special events for K-12 Hamilton County students, Chattanooga State Community College students, and community members. Accolades include the 2018 Tennessee Southeast Region Teacher of the Year, 2020 Chattanooga “Unsung Tech Hero,” and 2021 Microbit Champions. She holds a BS in Biology and a Masters of Education, is a National Board Certified Teacher, and is a member of the National Paideia Faculty.

Links

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.