Dustin Hensley and Elizabethton High School Graduates on Real-World Learning in Rural Tennessee

Key Points

-

Community-engaged learning empowers students to become active participants in their communities, fostering personal and professional growth.

-

Schools can become hubs of community learning by integrating real-world challenges and encouraging student-led initiatives.

In this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast, join Tom Vander Ark as he explores the transformative power of community-engaged learning with guests from Elizabethton High School in rural Tennessee. Discover how educators like Dustin Hensley are redefining education by integrating real-world challenges into the classroom, allowing students to develop crucial skills and a sense of purpose. Hear inspiring stories from alumni Veronica Watson and Sadie Whitehead, who share how these experiences have shaped their personal and professional lives. This conversation highlights the importance of student-centered education and the potential for community engagement to create meaningful learning opportunities. Tune in to learn how schools can become vibrant hubs for community connection and innovation

Outline

- (00:00) Introduction to Community Engaged Learning

- (02:45) Student-Centered Learning in Action

- (14:20) Leadership and Community Impact

- (27:19) The Role of AI in Community Learning

- (29:43) Advice for Educational Leaders

- (31:52) Conclusion and Final Thoughts

Introduction to Community Engaged Learning

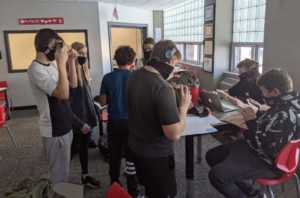

Tom Vander Ark: Community-engaged learning experiences in high school are incredibly valuable, particularly in rural education. Community-connected learning can help develop durable skills. It shapes agency, identity, and purpose and can influence college and career pathways. I’m Tom Vander Ark, and you’re listening to the Getting Smart Podcast. Today, we’re talking about community-engaged learning with friends from Eastern Tennessee, Elizabethton, and we’re starting with Dustin Hensley. Dustin is transforming American education from the library of Elizabethton High School.

Dustin, it’s really great to have you.

Dustin Hensley: Thank you. Thank you very much, Tom.

Tom Vander Ark: And Dustin has invited two alumni of his distinguished high school. We’re happy to have with us Veronica Watson and Sadie Whitehead. Hi, Veronica.

Veronica Watson: Hello.

Tom Vander Ark: And Sadie, it’s great to see you.

Sadie Whitehead: Thank you for having me.

Tom Vander Ark: You guys had an amazing experience in high school, and I can’t wait to dive into that. But Dustin, give us a little bit of the backstory. You’ve been there almost 10 years, I think. Is there more community-engaged learning now than there was when you got there, and if so, how did that happen?

Dustin Hensley: Yeah, for sure. I have been at Elizabethton High School since I was hired in June of 2015. So I’m getting ready to hit my 10-year anniversary. And whenever I first arrived at the high school, it’s a community that I grew up in. I did not go to Elizabethton High School. I went to a very close-by high school, but I knew Elizabethton High School very well. I know the community very well. So there was a lot of community love for the school, but there was not a lot of intentionality with what was happening between the school and the community. So whenever I started at the school in 2015, it was the same time that there was a national competition with XQ, the Super School competition, looking to redesign the next 100 years of high school. And I found that when I was trying to find a grant or a place, the flooring in the library that we had was the original furniture from the library from the 1970s; the carpeting was pretty old and outdated. So I was like, I want to find some grant funding. I’d been a grant writer in my previous district. I was like, I’ll fund some money for this. And then I found the XQ competition and thought $10 million could buy such good carpet. I’ll have like bamboo flooring in the library. It’ll be great.

Student-Centered Learning in Action

Dustin Hensley: So what we did with our application was we thought, who better knows about the high school experience than students? So we gave the application to our students and asked them to truly research and develop what they think the best high school experience would be for them. And one of the biggest things that came out of that was that they wanted to be part of their community, and they really didn’t like it when we would talk about the real world. We so often would tell them, well, it’ll be different in the real world, or when you’re in the real world, you’ll experience this. And they were like, we already live there. Like our houses are in the real world. We work jobs, like we go to community events, we go to church, like we do all these things already with people in the community. Why do you keep telling us that school’s a false reality or something, and we don’t like that? So we want to be actively engaged with our community while we’re learning and alongside them. So that was the forefront of our application with XQ, and we ended up being one of the first 13 XQ schools. And XQ did a lot of work supporting us in going towards community-engaged learning in our school. Our school is a traditional, comprehensive high school. We’ve been around since 1908. That is a lot of ingrained tradition that doesn’t necessarily want to lend itself to change and transformation.

Tom Vander Ark: And do you have like 400 kids, Dustin?

Dustin Hensley: We have 920 this school year.

Tom Vander Ark: Wow, so you’re a pretty good-sized school. And how big is the town?

Dustin Hensley: The town’s probably about 13,000.

Tom Vander Ark: So it’s pretty rural, and you’re way on the eastern tip of Tennessee, right?

Dustin Hensley: Yes, so we are bordering Virginia and North Carolina.

Tom Vander Ark: Dustin, where did that instinct come from, that the future would be more community-engaged experiences?

Dustin Hensley: Yeah, I think the crux of it came from wanting to be student-centered in action and more than just words. Because we say that all the time about lots of different things like student-centered learning and student voice, and we bandy it about a lot. But if you’re not actually doing anything with it, then you’re just using buzzwords. So we wanted to hold truth to that and put it in action. And whenever the students said they want to be involved with the community, then okay, then we need to create a way and a space that they are actively with the community. So what we did with Sadie’s class, she was in the first class, is we designed a course for students to do problem-seeking, problem-solving, and then try to create a solution and actually do their projects. So if you see this as an issue, this is the solution you created for it, then actually go forth with a partner in the community and do that action.

Tom Vander Ark: So what is that, in like ninth grade, Dustin?

Dustin Hensley: So, our first couple of iterations of it were specifically for junior and senior year. So that way they could leave, like they could drive themselves or get a ride to their community partners or their sites they were working with.

Tom Vander Ark: That is very cool. Let me just say this is really interesting, Dustin, because I just finished a blog about examples around the world of schools that are teaching community-connected learning, starting with problem finding. And I really think that’s one of the most important new skills that we can teach is to invite young people to find work that matters, to do. Right? Find stuff that’s important to you and to your community and to go do it. And we almost never give young people the space to do that. So what a cool instinct. So, Sadie, can you think of a project or two that you were able to frame up and where you could engage in something that was important to the community?

Sadie Whitehead: Yeah. Well, mine kind of started with the very issue that brought on the grant finding, you know, not carpet problems, but my mother is an educator and she is struggling with her elementary school students and keeping all of those across their experience engaged. So a lot of her more high-achieving students were sitting idle during this intervention study hall hour that they had. And she was really struggling with balancing that. And I was like, if my mom’s doing that and my mom’s awesome and can handle so much, I’m sure that this is something other educators are struggling with. And so, and I just love the concept of what XQ was doing. And I was like, well, we need to get everybody on board with this. So I began basically an enrichment program, but it was bringing in those more innovative styles of learning to elementary school. So I partnered with really awesome high schoolers and they were experts in what they were studying. We have a lot of great careers and technical sides of what Elizabethton does. And so I brought in health science students who were in health science classes at our school, aviation students, agriculture students. Veronica had her expertise with her computer science and with their interesting experience in those courses. We would take it to our elementary school students and build a lesson plan together, source what we needed to from donations and other guidance from other partners as we needed to. And we took those to the kids and let those kids kind of learn in a different cool way. And we had a great time. They had a great time. And it was really cool to see specifically these fourth and fifth graders trying something new, learning in a different way. And you could tell that they were kind of getting used to this new freedom that it also created of a different way to learn, which was huge. And a lot of my classmates were also doing incredible, incredible work. They were doing everything from community cleanup projects to the beautification of Elizabethton. Just so much of trying to invest back in our community in ways that spoke to them.

Tom Vander Ark: Those are great examples. Veronica, can you think of a project or two that really had an impact on you, maybe an impact on the community?

Veronica Watson: Yeah, absolutely. So, I got really excited about this program that I jumped into it headfirst way too early. So actually before freshman year even started, I was at orientation in the library being like, Hey, so you guys have this program, like, because you are doing this thing, can I, how can I be involved? So I started out helping Sadie as I think I was a freshman. The timeline’s a little fuzzy now because it’s been some distance, but yeah, I was a freshman but I had had at that point, like a couple of years of teaching experience in computer science already, specifically for elementary-age students. So getting to bring that and being invited into that space, being able to hang out with my upper-level peers created a sense of community within the school that was invaluable for me socially at the time. The stereotype of being a freshman in high school is not very nice. You know, it’s like, oh, they get picked on. So being able to be a part of something that was headed off by the seniors and stuff in the class is really awesome. And then to be able to do it in a way that furthered my professional goals. So I want to be a computer science teacher. I’ve decided now I want to do it at a university level. But I really care about computer science education and so I joined their program. Went to the elementary school, taught a session on Scratch, just doing basic programming and computational thinking with those students, and I really loved it. So when it was my turn the next year, sophomore year, still a year early, I made the plan to kind of expand more on my wedge of that program, so less broad like they were doing, but I wanted to get into multiple elementary schools. Tech time, you know, like when they have their specials block for computing. I wanted to actually make that useful and productive because in my experience in a couple of different school systems, that time was used for keyboarding, which is helpful and some Word and things, which are useful skills. But a lot of it at times felt redundant and it was a lot of cool math games and flash games and things under the guise of being educational. So my goal was to go into there and improve those. I pulled standards and mapped plans to standards and other school systems that were doing similar things to kind of prove the worth. And ultimately everybody was on board. Everybody was cool with me coming in. I couldn’t drive. So I had a really hard time finding other students to help me get into the schools on a regular basis. So I did unfortunately hit a little bit of a wall with that. But I just pivoted and found other projects to do that are a little bit more artsy and also kind of just tried to help me connect more with my school community, which eventually led me to being the student liaison, which is a student position on the school board. So I got that the end of junior year, and I sat for my senior year, which was, of course, the most awesome time sarcastic 2020. So COVID had just happened. Everything had gone remote. But I used that little bit of remote flexibility in my ability to kind of be in multiple places to try to really connect with people. The main thing that I did as a liaison was host a town hall event for students to ask the potential school board members. Because it was an election year, so we were gonna be bringing on more school board members. So I set up a town hall for the students to ask questions of their school board members to create this level of transparency about what the school board does and what students want, and to amplify that student voice just a little bit more to create a more connected community and a little bit more clarity. Because a lot of students are really good at finding problems, and they have a lot of them, and they get angry about them sometimes, and they have all of this passion. But it was often misdirected or unguided, and they didn’t know who to bring their problems to. They kept bringing it to teachers or their administrators not knowing that they really needed to take it all the way to the school board level to actually enact any kind of change. So I made that my initiative to kind of be this liaison between these students and the school board to kind of break down that barrier. I think when I was trying to get elected, because it was an elected position, which was super daunting for me because I was a nerdy little kid. I did not have a lot of friends. I won no popularity contests. I had beef with SGA. And so I was like, there’s no way I’m gonna get this. But I wanted it and I think I wanted it more than pretty much anybody else who was running. So I went and did the really scary thing and I went up to each group in the lunchroom, every group of kids at the table, and I was like, Hey, so we’re voting for this thing. First said, I’m like, can I bother you for a minute? And if they said no, I kept walking, which that alone got me a vote or two. ‘Cause like, sure, whatever. I’m not here to, you know, ruin your lunch. But then if they said I could, then I would tell them about the position, tell them about the school board and why I thought I could do a good job at it. And because of that self-advocacy, I got the position and it was, it was great and I was able to do at least some meaningful work. COVID definitely put a hindrance on I think the fullest I could do, but

Tom Vander Ark: So that’s awesome.

Leadership and Community Impact

Tom Vander Ark: I want to note that both of you, well, both of you described powerful learning experiences that took place in a class, but both of you also described leadership roles that you created or stepped into that were outside of class. So I love that you experience community-connected learning both in traditional ways in a class, but also outside of a class setting. Dustin, is that fair to say now that community-connected learning shows up in a variety of ways across the day at your high school?

Dustin Hensley: Yeah, for certain. That has been a priority that our school has put in place. We were able to just hire a community partnership coordinator this past school year. So we could really focus on making sure that on the curriculum end that we can make communication learning like our big focus for the school. Because we’ve talked for so long about what a powerful community we have and how much they love our high school. But now it’s time like, okay, how do we really make Elizabethton this learning ecosystem in which the high school’s the hub of learning? And that’s something that I’ve been really upfront about is that everyone here is a learner. Whether you are a teacher, a student, an administrator, the mayor, whoever you are, you are still a learner as a human. And we want you to be part of these learning experiences with our young people. So we’ve had a lot of our presentations of learning now will include audiences from the community, whether it’s professors from our local university or public officials, nonprofit execs, whoever it might be. We’re seeing a lot of people from the outside coming in and working with our students. Something that I’ve been really fortunate to be part of the past year is East Tennessee State University’s Honors College has moved towards, or completely towards, community-engaged learning now, and their program is called the Changemaker Scholars Program. And my community improvement class that these two were part of has now vertically aligned curriculum-wise with the opening class to the Changemaker Scholars program. So that way we’re able to do a lot of co-teaching that their students are gonna start coming to do mentoring work with our students on teaching how to do the problem seeking and problem-solving. ‘Cause I do that work with them. Like we use design thinking, we look at empathy mapping and things like that. But I see problems a lot differently as a 35-year-old than they do as 17-year-olds. And if a 20-year-old is working with them as a mentor, they can see problems much more similarly than I might be able to have that perspective.

Tom Vander Ark: I love that. And you’re the librarian there, right?

Dustin Hensley: Yes.

Tom Vander Ark: You’re really transforming what it means to be a librarian. You’re really transforming that community and the sort of new way that you’re leading through community-connected learning. It’s very exciting. Veronica, did these experiences, did it change how you experienced college, like where you went and what your expectations were and sort of how you engaged in a tech-centered degree program?

Veronica Watson: Yes. Short answer. Not even to be dramatic, but it’s kind of changed my whole life up to this point. It definitely forked me off in a direction that I have seen continuous benefit from. Having this understanding and constantly changing definition of what community is and how I play a role in it and the two-way street that it is, what I can give to my community and what my community would give to me. Having that basis just kind of made me a more empathetic person. It made me care a lot more about pretty much everything I was doing. You know, it gave me a sense of purpose. I can go to college, I can get a degree and I can have a career path. A lot of people do that because you need to live to a certain extent. Not everybody needs to go to college, but you know, finding some sort of career outline is a necessity, but having this opportunity to engage and look at things through a lens of community gave me the opportunity to not only pick a career but see how I can impact others and how that’s gonna grow me as a person too. I applied for two colleges. One was MIT and one was East Tennessee State University. I did not get into MIT in a large part of that I think is because my heart really wasn’t in it. You know, I had started really growing roots here and I use here kind of broadly. I’m in a different city now. I’m in Johnson City, but they’re sister cities. It’s the same region. So that’s my community. But, so yeah, I had started growing some roots here. I was starting to kind of like it, find my niche, find my flow. So I liked the idea of staying local. I was very blessed to have a full-ride scholarship that emphasized and fostered leadership and provided opportunities to grow as a leader in unique ways. And using that, it kind of also helped me form a bigger picture than just my classwork. You know, how is my classwork going to improve the lives of, of my life and others, especially in computer science. Oh my gosh, that’s a whole other world of can of worms. It’s such a unique program. The people in it are unique and so, so smart that it is intimidating at times. But being able to be in that space and have this understanding of community to kind of really bring a human element to something that can be so logical and critical I think really gave me a unique edge. And I’m gonna continue to carry that into grad school when I get a degree in AI in machine learning. So how this sense of humanity can be brought into something like AI and the ethics of it all. I’m really excited to dive into.

Tom Vander Ark: Beautiful testimony. You know, Dustin, we call this some of what we’ve been talking about, play-based learning. And you know, what you guys have done in the last eight years is invited kids to own their community, like to take it on and engage with it. Try to make it better. And we just heard Veronica describe how that changed her life, how she grew roots and really appreciated the assets of Eastern Tennessee. This really is life-changing work, isn’t it?

Dustin Hensley: Yeah, it really is. And that’s something that is necessary for our region that something that we’ve known here for a very long time is that we need to be the ones to save ourselves, whether it be from economic disparity or the drug epidemic. There are a lot of issues that we face here in Eastern Tennessee, in Appalachia as a whole. But if we are helping our young people, not just build those roots, but build the skills and help them understand how to use them across different contexts, that is so meaningful. And being able to see the fruit of the labor that we put in 10 years ago and seeing where the students are now that they’re in a career and making such a difference that those investments were worth it. So that, that’s what makes everything so powerful is seeing how they’re becoming not just productive members of society, but flourishing members of society who are making it a better place.

Tom Vander Ark: Yeah. We heard about deeper learning that took place. We heard about what Charles Fadel calls meta-learning, like where you’re learning about your own learning, right? And both of you, Sadie and Veronica, both talked about that, of coming to a better understanding of how you learn and how other people learn and how you can contribute. To learning, Sadie, you talked about that, like you understood your own learning and then you jumped into a role where you were helping little kids learn. And often teaching can be the best way to learn yourself. So I love that this, the community-engaged learning really promoted deeper learning and meta-learning. Sadie, did it change how you thought about college, how you engaged with college? I know you went down to Chattanooga, but did you find community-engaged learning there?

Sadie Whitehead: Yeah, so I mean, I think that the most challenging part can be putting yourself in those situations where you are gonna get connected and you are gonna be somebody who becomes invested in, whether it be a community, an institution, an organization, putting yourself out there to really behave as a citizen or a community member, team member. That takes a lot of courage and we don’t get a lot of practice at that in high school. We are expected to be in that seat and we take attendance and you know, but active participation is not necessarily always a requirement. And it might show in your grades, but it’s not always something, you know, something that’s required. But with the difference in having that experience in the community improvement course is that if I didn’t actively apply myself, if I didn’t care, then nobody was gonna do it for me. I was held accountable for sure, but in a different way, in a very empowering way. And then when I got to UTC, UT Chattanooga, I didn’t know a single soul and I had to use all those skills all over again. And so I got really involved with student leadership programs. So as in our student government association, I was actually external communications director for several years and then served on the student affairs committee. And all of that was more of kind of making those connections of how do we get other people involved in the things going on in their school and in their community. How do we as student leaders kind of be the torch holders for that whole concept? And then more than that, it’s changed definitely the career paths that I’ve taken and how I’ve grown in those ways. I currently work for a nonprofit that is doing a lot in the community of Chattanooga. And so it’s kind of necessary to the job to figure out how do you get involved with the people who are leading.

Tom Vander Ark: You’re like the volunteer coordinator, so you’re like, you’re wrangling volunteers. You’re building community like one person at a time.

Sadie Whitehead: I think that I’ve always just loved connecting people to purpose and mission and like people already have inherent passions and talents like we’re born with them and then some things we learn over time and we get very good at. But then how do we then go about utilizing it and how can you make your passions be bigger? It could be a career, it could be even just something you do in your spare time. And I think that I just love people who love things and I love people who are just good at things. And so I wanna do what I can to empower them to utilize those talents and skills. And actually, while being in the community improvement class, I got the opportunity to present two different times to our local community. And we invited, you know, nonprofit leaders. We invited members from colleges and leadership from colleges. We invited a lot of different people to these things and I had two different experiences where I then got approached and one of which was I was able to be an intern for United Way based on one of those presentations. And so even in our small United Way in Elizabethton, I got to then go into those rooms and those meetings and get to understand all of the people coming in to request funding and assistance from the United Way. And I got to learn even more from that experience. And so, I think that that’s just been where I’ve stayed and where I’ve kind of found home is working with those nonprofit leaders that are giving back and I think that’s what’s so vital, especially Dustin and Veronica, they live there still. And I have a different perspective because I’ve moved away. But in a town that’s that small, all of us have to pitch in to make it as great as it can be. And in a big city like this, you can get lost and if you kind of don’t do anything, things will still get done. But in a small rural community like Elizabeth, and I cherish the fact that so many people, so many people pitch in because it’s just what’s expected. It’s what you have to do to make it beautiful, to make it grow, to make it exciting for everybody. And I think that that’s why this has been the perfect thing for that small community because it’s just called that to action even further.

Tom Vander Ark: All right.

The Role of AI in Community Learning

Tom Vander Ark: Veronica’s the computer scientist on the call. I have this hunch that generative AI might help us do more and better community-engaged learning. It might help on that problem finding, it might help on the solution creation. It might help on impact delivery. What’s your take? Can it be helpful in doing more and better community-connected learning?

Veronica Watson: Yeah. I think AI can be helpful in a lot of different spaces. Really it boils down to intentionality and education. So we have to understand what AI is and how to use it ethically and conscientiously and with the right intentions. It’s, and much like a lot of things in life, it, it’s gonna exist on a pendulum. So we’re gonna see it swing to one extreme and then another before it levels out into being something useful and good. I definitely think it can help with community things, but I mean, you know, I’m not gonna walk down the street and start talking to an AI model. I’m gonna walk down the street and start talking to, you know, a guy named Matthew or some person. And so, yes, while AI is an incredible synthesis tool, to bring large amounts of information to a consumable level. I don’t think it will ever actually replace or be able to replicate the power of people in a community. It can definitely be a tool if you feed it a thousand data sets of in an Excel sheet, you know, like, oh, this is the census data for our city. You know, it can answer questions about that census data. A lot quicker of a way than somebody sitting down and reading and crunching those numbers themselves. It cannot answer moral questions safely yet. It cannot answer a lot of things that are innately human. It can’t be creative, it can’t be empathetic, and it can’t self-reflect yet either.

Tom Vander Ark: I appreciate how you and Sadie both have talked about people first making connections, building relationships, making a difference. Dustin, take us out with a word of advice for the ED leaders that are listening in.

Advice for Educational Leaders

Tom Vander Ark: Can you do this anywhere? Can any school add more community-engaged learning of the sort that we’ve talked about?

Dustin Hensley: Yeah, for sure. Regardless of what kind of community you’re in, whether it be rural or suburban, wherever you might be, you have a community in your school and you have a community around your school, and I think one of the most important things that you need to remember when doing this type of learning with students and doing problem seeking, problem-solving is to let them do the work. I’ve seen other places try to do this, and teachers immediately give the answers to the students. They’re like, oh, I think this would be a great solution to that and this would be a good solution. That’s not the point. If you’re doing all the cognitive lift and the students aren’t learning from this process, go work at a nonprofit. That’s what you’re trying to do. So let the students do the work and trust them. You’re there to guide them. A lot of times students would tell me, I wanna work on this, and I would say, here are the reasons I think that will not work. But if you wanna prove me wrong, then prove me wrong. Because your heart’s in the right place and you’re wanting to do it their way. I will give you advice, but you right here, you are the person doing the work and you’re the one that cares about this, and it’s your community. So trust in the students and let them have that freedom and let them know that they have the safety to fail, that you are there to support them and give them that safety net. That they can try these big ideas that we want them to be involved with their community. So even if you have a tiny community, you still have a community that is your school building and the tiny space around it and the families that live there. So no matter where you are, I say this is something that everyone should look forward to implement in their schools. I will say that we are getting to start a learning network in Appalachia. It’s gonna be called the Appalachian Futurism Project. So there’ll be a lot of information coming out about that soon. But a lot of that will be focused on community-engaged learning and how to take the history and culture of Appalachia and the context that we have and have our students and how to teach our students the skills to build their own future for Appalachia.

Tom Vander Ark: It’s beautiful.

Conclusion and Final Thoughts

Tom Vander Ark: Dustin Hensley is changing the world from a library at Elizabethton High School in East Tennessee. Veronica and Sadie loved your stories, appreciate your passion. It’s very cool to hear about the kind of community-engaged learning experiences that you had and how it changed you and how that changed your community. So thanks for joining us today.

Veronica Watson: Thanks for having us.

Sadie Whitehead: Thank you.

Tom Vander Ark: Thanks to our producer, Mason Pashia, and the whole Getting Smart team that makes this possible. And until next week, keep learning, keep leading, and keep framing up community-engaged learning experiences for kids. See you next week.

Links

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.