Charles Fadel on Education and Competencies for the Age of AI

Key Points

-

Educators need to understand that AI will have an impact on design and delivery.

-

Things don’t have to be measured to be embedded.

-

- Elementary and Middle School is preparation for life, high school is prearation for jobs. This means HS must pay more attention to types of knowledge that are needed.

On this episode of the Getting Smart Podcast Tom Vander Ark is joined by Charles Fadel, Founder of Center for Curriculum Redesign. Center for Curriculum Redesign is a leading authority on elementary and secondary outcomes and they recently published a great new book called Education for the Age of AI.

This book is one of the most thoughtful explorations of what skills humans will need to learn to do uniquely meaningful work alongside AI. It explores how many of the 21st century skills will be impacted by AI while also taking a look at Drivers of meaningful work.

Links:

- Education for the Age of AI

- Portrait Model | Getting Smart

- Center for Curriculum Redesign

- Cajon Valley

Transcript

Tom: We’re about fifteen months into a new age of human-computer interaction, and educational leaders around the world are thinking hard about what it means, how to change their learning goals, and how to improve their learning experiences. We’re lucky to be talking to Charles Fadel, founder of the Center for Curriculum Redesign, about what it all means. I’m Tom Vander Ark, and you’re listening to the Getting Smart Podcast. Today, we’re joined by Charles Fadel, whom I consider the leading authority on elementary and secondary education outcomes. I love his new book called “Education for the Age of AI.” Charles, it’s great to see you again, and thanks for joining us. Why did you write this book, Charles? What was the big thunderbolt that launched you into book writing again?

Charles: It’s my pleasure, Tom, thank you. Well, you know, I’ve been paying attention to AI since last century, quite honestly. With ChatGPT, I think we all realized that it’s finally here to a reasonable extent, and I will explain why “reasonable” in a moment. Now it’s something that we can actually act on in education circles. Past attempts at bringing this to the fore back in, let’s say, the 2016-2018 timeframe fell on deaf ears and got smothered away by COVID. But ChatGPT has finally put it in front of everyone, so we thought it was time to write about its implications for teaching and learning.

Tom: Charles, this is just a great book. It’s certainly one of the earliest and definitely the best examinations of what AI means for education, particularly for education outcomes, how we express them, how we assess them, and how AI will influence them. So, thanks to you and your team. You’ve obviously been busy. This is beautiful, timely work that we hope everybody reads. I want to jump into Chapter 4, where you summarize the high-level impact on education. How would you describe the high-level impact on education? And if you want to say a few words about today and then how this will evolve, feel free to do both.

Charles: Thank you, Tom. Well, first, to understand what’s needed in education, one has to accept the reality of what AI can and cannot do. There has been an enormous amount of hype about general intelligence AI being able to mimic entire human capabilities or super intelligence AI being far greater than humans, far better than humans. But the reality is that this is completely overrated. We are in an interesting phase, which a number of us call “capable AI.” This capable AI phase does not mean that jobs will disappear; they will morph into needing that tool, of course, the same way that the spreadsheet forced an accountant or bookkeeper to start using spreadsheets instead of pen and paper. So this is a new tool, very powerful. It impacts language-related activities but not necessarily other types of activities. That means that, by and large, jobs will still be here, just a bit different. As usual, we are terrible at imagining the new jobs that emerge when new technologies show up. For example, would anyone have thought of “influencer” as being a job? And yet here we are, it is. So I wanted to say this because we have to be really careful.

High school is a preparation for jobs in addition to continuing middle school and elementary school’s preparation for life. We are not in a position to say high school should only have outcomes related to life and none related to jobs. It has to be both. With that preamble, high school has to be redesigned to pay more attention to different types of knowledge that are needed. Pay more attention to procedural knowledge and conceptual knowledge, not just facts and figures, meaning declarative knowledge. The internet and AI can do really well at declarative knowledge. Again, we have to be careful here. It’s not all of it; it’s about being choosy about what type of knowledge is meaningful. We need to redesign the curricula with that in mind.

So, number one: curate knowledge in traditional disciplines. Why so much trigonometry and so little data science? Second, in this modernization of knowledge, why wouldn’t we teach technology and engineering? We call it STEM, but we really only teach math and science. We don’t teach civil, mechanical, electrical engineering. If you’re lucky, your school offers computer science. No biotech, typically. It’s not just basic biology or microbiology. We don’t really teach technology and engineering. Why wouldn’t we be teaching entrepreneurship rather than traditional business? Entrepreneurship is the job of the future. Why wouldn’t we be teaching social sciences to everyone if understanding yourself and others matters so much in this age? Why wouldn’t we be teaching psychology, sociology, and anthropology in high school as mandatory topics? Well, we can’t because traditional disciplines have taken up all the time. That’s what we mean by curating knowledge and leaving room for modern disciplines and modernized subjects and topics of existing disciplines.

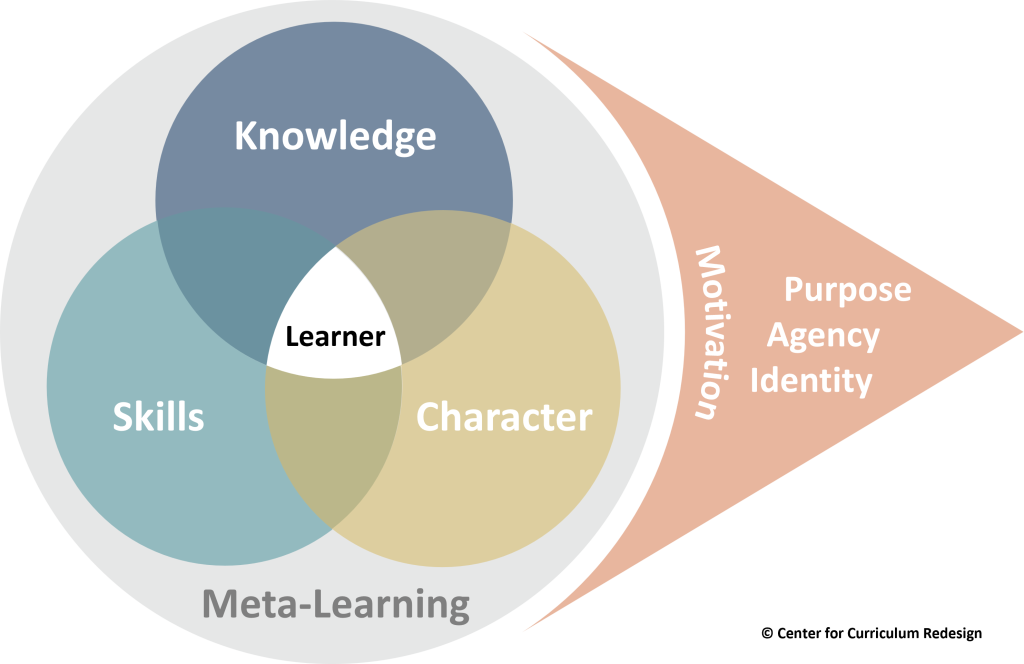

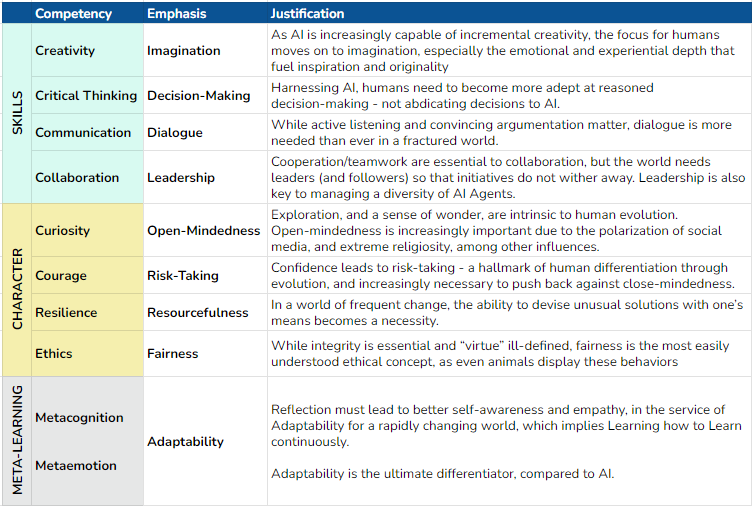

Second, we need to finally get to the point where we teach competencies. We’ve been talking about them for decades. My first book was called “Twenty-First Century Skills.” It became the moniker used worldwide. But I’m still frustrated by the fact that no jurisdiction, not even Singapore or Finland, has truly embedded the teaching of critical thinking, creativity, curiosity, and so on within their curricula. It’s only added as an add-on on top of everything else rather than being part and parcel of how education happens. We need to teach skills in character and meta-learning in an embedded way in the disciplines. These things are the new requirements: curating knowledge, ensuring competencies are taught, and finally, we have also identified what we call drivers. Drivers relate to the motivation of the student, the personalization aspect. They relate to identity, agency, and purpose. That’s what we need to pay a lot more attention to because if it can be found on the internet or an AI can give me the answer, why do I need to work hard? That’s the typical question from a student. To motivate them, we have to pay attention to their identity and belonging, their agency and growth mindset, and their purpose and passions.

Tom: Charles, I see a couple of different camps emerging in terms of how and where AI is being used. There’s Sal Khan and Khan Academy developing Khanmigo, advocating for AI as an intelligent tutor. I also read Ethan Mollick’s column, the professor at Wharton, who invites his learners to use AI in entrepreneurship. So that’s AI as a creation engine. Which of those are you enthusiastic about, or what are your thoughts on AI as a tutor or a creation engine?

Charles: Both, quite honestly. There’s the design and there’s the delivery. AI is going to be used for both. Whether you’re a teacher, professor, or student, it’s going to help you design your outputs a lot better. You’re going to have access to a helper of sorts to help you create. And I don’t mean create necessarily in an artistic sense; I mean in a textual sense or conceptual sense. We can design curricula, for instance. We can take a book, like from OpenStax, and feed it into an AI system, well-trained, like the one we’re designing, to give you credible answers and design lesson plans for you based on real knowledge that has been curated, rather than just knowledge you find anywhere on the internet. That’s the design side. The deployment side is intelligent tutoring systems. They have a lot of promise, of course, but there are really a couple of caveats to pay attention to. First, they should not be an “or” proposition; they should be an “and” proposition. The student still needs social engagement with peers, teachers, and so on. It cannot be just in isolation. Second, these ITSs may be more effective with vertical disciplines like mathematics, which are more threaded and systematic than, say, literature or philosophy. The verticalization of the discipline may impact how far you can put an intelligent tutor because climbing a ladder step-by-step is easier than having an open-ended conversation about a philosophical concept. So there’s analysis needed to see where they can help the most. And as always, this is a helper to the teacher, not just the student. The teacher has to be capable of designing and digesting the capabilities of an AI, not feel threatened by it, and know how to work with an ITS as a helper for the student.

Tom: It’s interesting you mention these intelligent tutoring systems. There are a couple of new micro-schools that advertise no teachers; you just learn with an AI tutor. Is that the future, or is the future more teachers empowered by teaching assistants and tutoring systems?

Charles: That model of only technology works, in my opinion, only when you don’t have solid teachers. If you’re a poor country with no teachers whatsoever, sure, that’s better than nothing. It’s a bit like learning off YouTube but with more guidance than just YouTube or an online course. But really, that would be the lowest form of AI usage, and it would diminish the role of teachers in an unacceptable way. We know from learning sciences that peer learning and social learning matter enormously. My comments about vertical disciplines apply as well. This may work better for math than for language. I would be terribly skeptical about a technology-only model, including AI.

Tom: Charles, we just issued a report called the Portrait Model, a gallery of learning objectives of school systems around the country. None of those included wisdom, but in Chapter 3, you argue that wisdom is the enduring goal of education. It made me smile. It was a beautiful chapter. Why is wisdom more important than ever?

Charles: Well, perhaps it’s my age dictating this, but we are definitely not the first to talk about wisdom for education. You can go back to Confucius and Socrates and any number of philosophers who talked about it. So what is wisdom? It’s the synthesis of knowledge, skills, character, and meta-learning. You can have an enormous amount of knowledge and still not be wise. Wisdom is about the long-term perspective and patience to discern what to pay attention to. Knowledge is a grain of sand in a sand dune. Wisdom is the sand dune. If you think about the typical stakeholder of education, policymakers, they have to juggle many priorities. They have to understand the effects of decisions decades from now. They need to be wise and, as we know, they aren’t always wise. The same applies to teachers and parents. Teachers need to have patience with students and pay attention to their individual learning needs. That requires wisdom. Parents need to know when to pressure their kids and when to relax, which takes wisdom. So we need to broaden the perspective of education from just knowledge and skills to wisdom. This helps us pay attention to the whole human being and their long-term development.

Tom: In the context of AI, particularly, there’s a danger that kids might rely too heavily on AI, lose curiosity, and miss the development of critical thinking. How do we balance the benefits of AI in education while ensuring students remain curious and develop critical thinking skills?

Charles: That’s a fantastic question, Tom. We need to be extremely vigilant about how AI is used in education. AI should be seen as a tool to augment human capabilities, not replace them. We have to design learning experiences that encourage students to ask questions, explore, and engage deeply with the material. AI can provide personalized feedback and resources, but it should not be the sole source of knowledge or the only method of learning. We must ensure that students are still given opportunities for inquiry-based learning, problem-solving, and collaboration. These activities foster curiosity and critical thinking. Educators need to be trained on how to integrate AI effectively into their teaching practices, balancing it with traditional methods that promote these essential skills.

Tom: You’ve mentioned before that education needs to be more interdisciplinary. Can you elaborate on why that’s important and how AI can support interdisciplinary learning?

Charles: Absolutely. The real world is not divided into neat disciplinary boundaries. Problems are complex and require knowledge and skills from multiple disciplines to solve. Interdisciplinary learning prepares students to think holistically and apply their knowledge in diverse contexts. AI can support this by helping to create integrated curricula that draw connections between subjects. For example, a project on climate change can incorporate science, economics, social studies, and technology. AI can provide resources, suggest relevant activities, and even help students see the connections between different fields. By using AI to design and deliver interdisciplinary learning experiences, we can help students develop a more comprehensive understanding of the world and better prepare them for future challenges.

Tom: It’s clear that AI has the potential to transform education, but there are also risks involved. What are some of the ethical considerations we need to keep in mind as we integrate AI into education?

Charles: Ethical considerations are paramount when it comes to integrating AI into education. Privacy is a major concern. We need to ensure that students’ data is protected and used responsibly. There’s also the risk of bias in AI systems, which can perpetuate existing inequalities. We must be vigilant in testing and auditing AI tools to ensure they are fair and unbiased. Another consideration is the impact on the teacher-student relationship. AI should enhance this relationship, not replace it. Teachers play a crucial role in providing emotional support, mentorship, and human connection, which AI cannot replicate. Finally, we need to think about the implications of AI on the workforce. As AI changes the nature of work, education systems must adapt to prepare students for new types of jobs and ways of working. This includes teaching them how to work alongside AI and developing skills that AI cannot easily replicate, such as creativity, empathy, and collaboration.

Tom: Charles, this has been a fascinating conversation. Thank you so much for sharing your insights with us today. Do you have any final thoughts or advice for educators and policymakers as they navigate this new era of AI in education?

Charles: Thank you, Tom. My final advice would be to stay informed and proactive. AI is evolving rapidly, and it’s crucial for educators and policymakers to stay up-to-date with the latest developments and understand their implications for education. Embrace the opportunities that AI offers, but do so thoughtfully and ethically. Focus on developing a balanced approach that leverages AI to enhance teaching and learning while preserving the essential human elements of education. And finally, prioritize the holistic development of students. Ensure that they are not only acquiring knowledge and skills but also developing character, critical thinking, and a sense of purpose. By doing so, we can prepare them to thrive in a world increasingly shaped by AI.

Tom: Thank you, Charles. It’s been a pleasure talking with you. And thank you to our listeners for tuning in to the Getting Smart Podcast. Be sure to check out Charles Fadel’s new book, “Education for the Age of AI,” and visit the Center for Curriculum Redesign’s website for more resources on how to adapt education for the future.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.