At Two Schools for Elite Athletes, the Passion is the Point

Key Points

-

Schools like YSC Academy and Burke Mountain Academy exemplify how aligning education with students’ passions can foster success and well-rounded development, even if they don’t achieve their initial athletic goals.

-

Emphasizing mental health, executive functioning, and flexible learning schedules prepares students for life’s pressures while supporting their dreams.

Even as a kid, Richie Graham was different.

In the football-crazed landscape of Southeast Pennsylvania, he preferred to play soccer. And amidst a topography that was more about rolling hills than steep slopes, he aspired to become an Olympic skier.

Yet aside from his atypical hobbies, Graham also possessed an atypical drive: one that led him to leave home early in pursuit of his dreams, and one that now, after amassing a small fortune (and an ownership stake in his home state’s Major League Soccer franchise), has added a new title to his list of accomplishments: School Founder.

“At the heart of it,” he explained to me recently, “traditional education systems don’t meet kids with a passion at their passion point. And yet the lessons that come from fully pursuing your passions are the ones that really teach you who you are.

“That’s what I learned at Burke. And that’s what we’re building at YSC.”

The ‘Burke’ is Burke Mountain Academy, a small residential school, first founded in 1970 and spread across nearly thirty-five acres of northern Vermont mountainside. For Graham, it was a life-changing place.

“The culture at Burke was a big shift for me as a young person,” he said . “I felt like I had finally found my people, where it was the expectation that everyone should work hard and do well.”

To make it so, Burke organizes itself around the training needs of its student athletes. In the warmer months, kids work out in the morning, attend classes from mid-morning to mid-afternoon, and train once more before dinner. “But whenever the weather was right,” Graham recalled, “we’d ski all morning, and shift school to the afternoon and evening. And if there was ever a surprise snowfall, no one needed to wonder if classes would be canceled.”

As Burke’s founder, Warren Witherell, once famously said, “You should never let school get in the way of a good education.”

At the same time, Witherell understood that only a few ‘Burkies’ would actually become Olympians. “These are youngsters with a big dream,” he explained. “What we do is help them chase it.”

And, in the process, teach them not just how to ski, but how to be.

Consequently, like most of his classmates, Richie Graham never became a championship skier. Yet his time there helped steer him to Dartmouth, instilling the habits that would fuel his professional success. So when, years later, Graham got involved in the world of pro soccer, he noticed a glaring absence — and resolved to fill the void himself.

Not coincidentally, Graham’s club, Philadelphia Union, is a perennial contender — in part because of its success at identifying, and then cultivating, “homegrown” talent: the top young players who hail from a 75-mile radius around each club’s home stadium, and who, if they have what it takes to rise all the way to the first team, can develop with a clear understanding of the Union’s game model and style of play.

“Our club has one of the lowest roster spends in the league because of our success developing homegrown players,” Graham told me. “It allows us to be smarter in how we blend the mix of our roster and allocate our money overall. Yet some of the league’s other owners are still reluctant to make the necessary investment in player development. To me, though, it’s simple: the future of American soccer is the American player. We have to build our own pipeline. And you simply can’t develop world class players from 4-6 Monday through Friday with a game on the weekend. You have to go all in to create an immersive, culture driven environment that integrates physical training, intellectual and social development, and meets players at their passion point.”

In response, Graham resolved to give the Union a competitive advantage in its cultivation of homegrown talent. And as he got to know the head of the school where his own children attended, he suspected he’d found his Warren Witherell.

Nooha Ahmed-Lee had never been an elite athlete. She wasn’t even a soccer fan. But she was a lifelong educator and school leader, with a specialized understanding of the adolescent brain.

“I told her I wanted to create an environment where kids could pursue their dreams without sacrificing their education,” Graham recounted, “and she said she wanted to start a school that was built for teens, not soccer stars.”

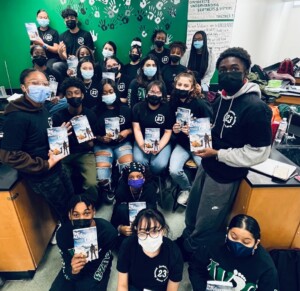

Their experiment began in 2013, with seven students in a leased office space opposite a local training facility. Today, it encompasses a converted electrical plant that sits at the edge of the Delaware River, alongside the Union’s sprawling new $100 million training complex.

It’s called YSC Academy, and its eighty middle- and high-school students train first thing each weekday morning. Classes don’t start until eleven here, which, like everything else at YSC, is by design.

“At any school,” Ahmed-Lee explained as a sea of boys filed past her to grab their post-training breakfast, “children should be active at the outset. Exercising in the morning helps you learn, and gets your metabolism going. That’s good practice whether you’re an elite athlete or not.”

So, too, is an explicit emphasis on executive functioning and self-direction skills.

“Early on,” Ahmed-Lee explained, “we had staff who were experts in content but who maybe loved their subjects more than kids. Yet our vision was to place student-athletes, not teachers, at the center of the learning process, and to do so in ways that emphasized ownership, creativity, and problem-solving. Because of the nature of our students’ lives, we knew we’d also have to constantly modify our schedule and our strategies to accommodate their soccer-related demands. So we’re really good at toggling between the different modes of teaching to match whatever our boys need at a given moment, from in-person to asynchronous. We’ve even designed our own virtual learning platform, which is allowing us to teach kids at other academies as well.

“Then again,” she continued, “dual-track learning is the way of the world now. The games will be played on both grass and turf. It’s different, and you better be able to excel on both.”

It’s also a high-pressure world these kids inhabit, housed by a host of kids who are living away from home to precariously pursue their dreams.

That’s why Ahmed-Lee hired Keith Wilford as YSC’s mental health and wellness coordinator. Willford is a former professional football and lacrosse player. And perhaps because of his own experiences, he’s able to see beyond the seemingly unshakeable self-confidence of his students. “This is an extraordinary environment for some extraordinary young people,” he began, “but that doesn’t change the fact that they’re terrified.”

Of leaving home.

Of wondering whether they’ll make it.

Of questioning whether it’s all worth it.

“When you’re in this highly elite bubble,” Ahmed-Lee added, “and decisions about their playing time and their future at the club are always hanging in the air, the school must be the place that instills in them an unconditional sense of love and support.

“The business side is cold. So it’s vital that the school side be warm.”

Indeed, as at Burke, the majority of YSC’s graduates will not become pro players. But under the guidance of Ahmed-Lee and her team, they will become well-prepared, well-rounded young men.

“What do kids need?” she asked me as the end of the school day neared, two parent volunteers steadily blending eighty fruit smoothies nearby as a pre-training snack. “Movement. Hydration. Nutrition. Connection. And sleep. So we’ve created a schedule based on what their brains need. And although soccer has been the impetus for us to do that, the central recipe is vital regardless.

If we’re going to be successful, our program has to widen their aperture. We need to legitimize all the ways our kids can lead their lives. And we need to give them an environment where they can make choices, show what they know, and feel surrounded by caring adults.

“The art of teaching, mixed with the science of learning and development. That’s the future, for all of us.”

Photo Credit: Sam Chaltain

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.