How Do You Build a Learner-Centered Ecosystem?

Key Points

-

It’s not just about redesigning public education—it’s about rethinking how, where and with whom learning happens. Communities across the United States are shaping learner-centered ecosystems and gathering insights along the way.

-

What does it take to build a learner-centered ecosystem? A shared vision. Distributed leadership. Place-based experiences. Repurposed resources. And more. This piece unpacks 10 real-world insights from pilots in action.

By: Bobbi Macdonald and Alin Bennett

All photos in this post were taken by Joanna Zhang.

What new shapes might education need to assume if we wish to properly equip young people for their future — as opposed to our past?

In what new ways will adults and children need to lead to ensure that each child’s educational journey is truly learner-centered and community-embedded?

And how can we center our humanity and better engage across sectors and disciplines to face the complex challenges of today and tomorrow?

At Education Reimagined, these questions drive everything we do. After all, every child in America deserves an education that will help them develop their gifts — and discover how to share those gifts meaningfully with the wider world.

To get there from here, however, we must reimagine the ways we engage young people for life after graduation. We must devise a new architecture that is more guided by the adaptive power of living systems than the stifling controls of the Industrial Era. And we must find new ways of activating the wisdom of each community — and the wide variety of people, settings, and pathways they contain.

We believe the path forward is through the cultivation of learner-centered ecosystems — adaptive, networked structures that offer a transformed way of organizing, supporting, and credentialing community-wide learning. These ecosystems break down barriers between schools, communities, and industries, creating flexible, real-world learning experiences that tap into the full range of opportunities a community has to offer — and ensuring that learning is relevant, inclusive, and deeply rooted in its unique strengths and attributes.

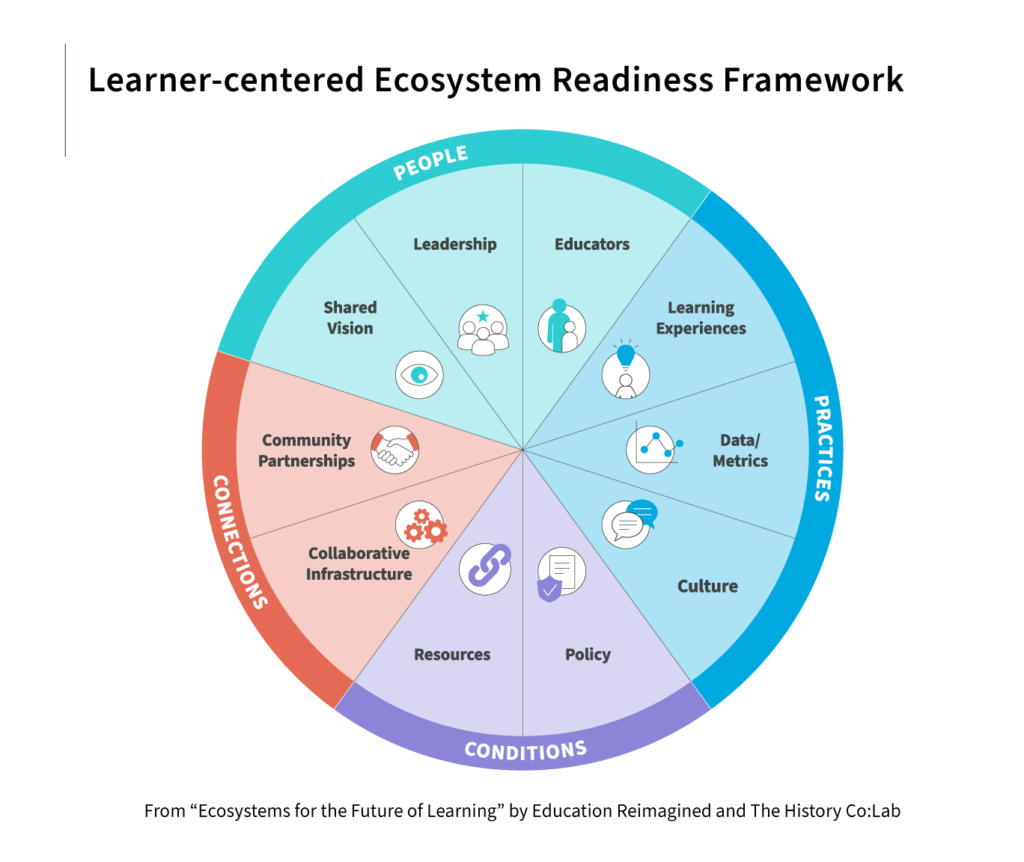

Last year, we announced our Learner-Centered Ecosystem Lab, a collaborative effort to create a community of practice consisting of twelve diverse sites across the country — from the streets of Brooklyn to the mountains of Ojai — that are demonstrating or piloting ecosystemic approaches. Since then, we’ve been gathering together, learning from one another, and facing the challenges and opportunities of trying to transform public education. And while there is still much more work to be done, we’ve begun to observe a deeper pattern language — one that aligns with our ten-point Ecosystem Readiness Framework, and one that, we hope, can help all communities start to think more practically and creatively about how to transform their own systems of learning.

So while it’s still early, we suspect that the way to establish a healthy learner-centered ecosystem is by paying close attention to the following ten conditions:

1. Vision | Must be Shared

In a learner-centered ecosystem, the entire community must have a common understanding of the purpose of public education — and the role different organizations can play in fulfilling that purpose. This is what you’ll find in Newport, Rhode Island, where community makerspace FabNewport has spent the past ten years cultivating a collective commitment across the entire city. They do this through responding to the interests of the children, the needs of the businesses, the hopes of the non profits – all coming together in community meetings, events, and exhibitions of student work to continually revise and develop a shared vision. “Newport has such a wide array of experiences for kids,” says founder Steve Heath. “And now, because of the work we’ve put into weaving together the different programs and expertise that everyone can provide, we’re poised to start treating the city as our shared classroom.”

2. Leadership | Must be Distributed

Sustained and sustaining distributed leadership structures with strong relationships and interconnectedness form the basis of any healthy ecosystem. That’s what’s happening at Rock Tree Sky, a self-directed learning community in Ojai, California, that’s extending its work throughout the city by forming a community steering committee and cultivating strong civic partnerships. Together they are launching the Ojai Learning Ecosystem. As co-founder Jim Bailey put it, “The beauty of an ecosystem is the interrelationship of its parts. Through our work with others in Ojai, we’re starting to create those connections here.”

3. Learning Experiences | Must be Meaning-Full

We’ve all known for some time now that a great learning experience is challenging, engaging, relevant, supportive, and experiential. But in a learner-centered ecosystem, this insight shapes every aspect of a young person’s experiences. With the help of Spark NC, for example, seventeen school districts across the state have come together to establish “SparkLabs” — physical hubs that expose learners to seven different high-tech fields, and offer stackable learning experiences that can be combined for high school credit. As SparkNC’s Vice president of Strategy Dana Brinson put it, “these learning experiences give Spark Scholars an opportunity to hone their skills and build a portfolio of work that gives them a competitive edge in entering high-demand, high-wage careers.”

4. Community Partnerships | Must be Cultivated

Schools and districts can’t do this alone. As we make clear in our 2023 report, “transitioning to a learning ecosystem is not just about improving outcomes for individual students, it is about strengthening the social fabric and advancing the civic renewal of communities by integrating young people as changemakers through an infrastructure that cultivates and nurtures partnerships. The emerging vision of Runway Green in Brooklyn stands as a remarkable example of this principle in action. Designed to occupy seven acres of a 1,300 acre National Park Service reserve, the staff at Runway are working to coalesce the myriad public-private partnerships — from SolarOne and the Billion Oyster Project to the Campaign Against Hunger and NYC Outward Bound — that are required to see an idea this big all the way through to reality. “This idea is not a school,” explains founder Geoffrey Roehm. “It’s part of what we see as a new design for learning, which is to take all the assets that exist within a community and open them up as learning opportunities for kids that are powerful and real and community-based.”

5. Collaborative Infrastructure | Must be Created

Although it’s not flashy, it’s vital that learner-centered ecosystems adopt learning management systems and collaboration platforms that can support community-connected learning at scale, and establish flexible systems for scheduling, transportation, and assessment. That’s what’s happening in Dallas, where Big Thought, a national leader in arts education, out-of-school programming, social emotional learning, youth justice, and learning systems, has revolutionized how young people navigate their learning journeys by combining digital badges with a Youth Journey Mapping tool. As Big Thought’s Director of Learning Systems Kristina Cola put it, “this approach amplifies youth voice and interests, connects aspirations to achievements, and builds a more equitable, connected learning ecosystem where every learner’s unique path, including their experiences and mentors, is celebrated and supported.”

6. Policies | Must be Enabling

There is the question of policy — and the riddle of which sorts can best support the growth of learner-centered ecosystems. But one promising example comes from Ohio’s capital city, where an evolving partnership between the PAST Foundation, schools, businesses, policymakers, and civic allies have launched the Columbus EcosySTEM to demonstrate what a completely different approach to education would look like — and require. And a big reason for that effort’s early success is the policy landscape in Ohio, which is providing a useful model for how states can free up educators and kids to pursue a wider range of learning pathways. In 2006, Ohio began allowing high school students to earn college credit for free while in high school. Ohio’s prioritization of aligning K-12 education and workforce has opened the door to encouraging cross sector collaboration and learner-centered approaches, and created broader conditions to allow for more learner-centered approaches, programs, and partnerships — from adopting whole-child and personalized learning frameworks to incentivizing work-based learning opportunities. And while there’s still more work to be done, the primary obstacle is not about policy, but perception. “There’s nothing that says you have to teach this way,” said Marcy Raymond, a lifelong educator who is a part of the EcosySTEM work. “There’s nothing that says you can’t prioritize your relationships with students and have a learner-centered environment. There’s nothing that says your ecosystem has to be static.”

7. Resources | Must be Repurposed

Learner-centered ecosystems have the potential to solve some of our biggest civic challenges when it comes to the optimal allocation of resources and assets. Indeed, finding ways to utilize existing resources for multiple purposes and users has been one of our biggest learnings from the Lab so far. A good example of this is Liberty Public Schools (LPS), a historic public school district in Kansas City that is developing career-focused learning hubs across the community — and tapping into underutilized, district-owned land to create an environmental science-focused learning hub that will serve as a model for additional hubs and career pathways. “Our work builds on existing community partnerships,” explains Liberty’s assistant superintendent Julie Moore, “but it also helps reduce the strain on transportation, and increases access to internships so that every learner in our district can engage in meaningful career exploration and start charting a clear path for themselves after they graduate.”

Similarly, in Indianapolis, the Purdue Polytechnic (PPHS) network of high schools is offering the city’s young people a range of “home-base” options — from large learning communities to microschools of just twenty students — from which they can explore different possible career pathways. “Different kids thrive in different contexts,” explained Lacey Beatty, PPHS’s Director of Leadership Development. “So if we’re serious about creating a true ecosystem, the more shapes and sizes we can offer kids for their learning environments, the better.”

8. Educators | Must be Flexible

Of the many arenas of education transformation that the field is grappling with, the role of the educator has been at the forefront. As the Age of AI has transformed our relationship to information, educators have an opportunity to prioritize mentorship more than content delivery. This is what they’ve done in the Norris School District, a small district in rural Wisconsin that has transformed the functions and roles of its educators. Instead of traditional classroom teachers, they have Navigators, who are responsible for building cultures of belonging and helping learners explore their passions. And they have “externship mentors,” community members who have agreed to host one or more young learners to create experiential opportunities, support career pathway exploration, and foster the development of healthy adolescent identities. “At Norris,” explains executive director Johnna Noll, “we build the capacity of individuals and organizations to take the next steps in the iterative development of responsive enduring practices that are the fibers of a learner-centered culture.”

9. Metrics | Must be Holistic

All successful organizations must “measure what matters” so they can continually learn, grow, and evolve. In education, however, this is a riddle we have yet to solve — opting instead to measure what we can, not what we must. A vital prerequisite for any learner-centered ecosystem, then, is to identify and track a set of holistic outcomes. And while there will surely be some common metrics across communities, each community’s unique context, challenges, and culture must also be accounted for. This is the approach of the NACA Inspired Schools Network (NISN), an organization that works with Indigenous communities to establish schools in New Mexico and throughout the country that will create strong leaders who are academically prepared, secure in their identities, healthy, and ultimately transforming their communities. To that end, NACA has implemented the Mission-driven Story Cycle (MDSC), a framework that ensures learning and decision-making remain aligned with a community’s deeper mission and values. “If we want to support the holistic development and growth of young people,” says NACA’s Director of Operations, Matthew Kull, “we must identify ways to measure our organization’s capacity to provide those opportunities — and whether or not they’ve been effective.”

10. Culture | Must be Inclusive

Reimagining how culture is created, developed, and sustained within an ecosystemic framework has been a primary goal of many of the leaders in the Ecosystem Lab. “The challenge,” explains Coi Morefield, founder of the Lab School of Memphis, ”is how best to weave together a diverse set of institutions, each of which have their own contexts and concerns.” So when Morefield noticed a stark difference in how learners were seen and treated elsewhere in the city, she stepped into action to help build the sense of shared culture across the wider ecosystem. The result is a collection of resources for learners, families, and educators, and an explicitly stated understanding of how community partners can contribute to the Culture of the Lab School in ways that match the values their community holds most dear.

Similarly, South Valley High, a Big Picture Learning school in Ukiah, California, students are leading Participatory Action Research (PAR) projects to examine the biggest barriers to community-wide wellness. Rooted in deep collaboration with staff, community partners, tribal communities, and families, this student-driven inquiry is shedding light on critical issues like substance abuse and health and wellness challenges that impact student success. And by centering youth voices in the research process, Ukiah is not only fostering a culture of agency and belonging, but also ensuring that the solutions reflect the lived experiences and priorities of those most affected. “This approach demonstrates how an inclusive culture can emerge,” said principal Kita Grinberg, “when young people are empowered to ask big questions, shape the learning environment, and build meaningful partnerships with the broader community.”

Ten conditions. Ten priorities. And ten markers of a more modern, equitable system — an ecosystem, in fact — that works for all young people, and protects the vital benefits of public education for generations to come.

At Education Reimagined, we’ve been connecting and cultivating a vibrant movement of learner-centered changemakers for more than a decade. And now, with the work of our Ecosystem Lab, we’re starting to see the deeper patterns that can unlock a new era of learning — and a new chapter in the long history of American education.

The world’s changing faster than ever before.

It’s time for education to catch up.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.