What Should Graduates Know and Be Able to Do?

Ken Kay has been advocating for 21st Century Skills since they were a prediction. As past president of the Partnership for 21st Century Skills and founder of EdLeader21 (now part of Battelle for Kids), he’s led a lot of conversations about what high school graduates should know.

EdLeader21 launched the Profile of a Graduate project in 2017 to provide examples of updated graduate profiles and a roadmap that school districts can adapt to host their own conversations (see Battelle’s PortraitofaGraduate.org).

After a recent conference, Ken and I corresponded about the role of community engagement:

KK: It is very productive and important to have community conversations around vision and goals like the portrait of a graduate.

TVA: Like you, we’ve found it very important for school districts to engage their community in the discussion about how the world is changing, what that means for the employment landscape and, as a result, what graduates should know and be able to do. In fact, prioritizing new outcomes (like collaboration) and then changing practices and parent reporting without having the conversation is a good way to get fired.

KK: Critical issues that are part of the vision or direction, like equity, need to be part of the community conversation.

TVA: Right. I find the question of equity to be particularly challenging now that everyone is talking about career and technical pathways, some of which are very attractive alternatives to traditional higher education while others lead to dead-end jobs. The distinctions between a high potential and dead-end job cluster are fine-grained and localized and require well-informed guidance.

KK: It is much more difficult, and in some cases counterproductive, to have community conversations with the idea of getting consensus around implementation strategies. For example, I wouldn’t try to get a community consensus on whether or how to deploy PBL. Many in the community don’t know what it is and I consider pedagogies to be the domain of the educators.

TVA: We need coherent school models that work well for teachers and students—and those aren’t designed by consensus, they are the product of research-backed learning engineering. Designs are complicated by the fact that ed tech hasn’t caught up with aspirations of personalized and competency-based learning–it’s still really hard to build a tech stack that supports new models. (Our new book, Better Together suggests schools consider joining school networks to reduce the degree of difficulty to offer high quality personalized learning.)

However, as Paul Hill noted in his 1997 classic, Reinventing Public Education, governing bodies have an obligation to lead conversations about the kinds of schools the community needs and wants—classical or high tech schools, college and/or career prep, big schools with selective sports or small supportive schools.

One problem with this dialog is that people only know the schools they experienced. Most educators haven’t had the chance to visit a lot of schools and see what kinds of options exist.

To inform this sort of dialog in Kansas City, the Kauffman Foundation has sponsored visits to great schools around the country—over 300 people have visited 70 schools in 12 cities.

KK: I agree a great deal of outreach and knowledge building is required with parents and students around topics like report cards and “interface” issues. But I view these as outreach, listening and refining sessions rather than consensus building. I am not sure one can ever build a consensus around topics like report cards.

TVA: I remember, as a new superintendent, introducing a big standards-based report card on our teachers and parents without much input and it blew up. You’re right, you can’t develop these systems by consensus, but it sure requires some outreach.

We’re big fans of design thinking, a process that starts with understanding the problem and a phase of “empathy research,” an effort to deeply understand customer values, needs and use patterns. (Human-centered design calls it participatory action research.) Design thinking continues with iterative design—starting small and failing small, and making improvement in rapid cycles.

It’s worth differentiating innovation, something new and different, from improvement, an improvement to an existing system. It takes a lot more political capital to innovate that it does to improve. A school faculty could decide to focus on an area of improvement without much input but if they want to do something radically different, they need to facilitate a community agreement especially if it costs a lot, involves risk, or threatens long-held values. (Listen to a discussion on innovation vs improvement.)

KK: I hope this distinction is helpful between those topics that the community should have a major role in setting direction and those where the public needs to be informed and engaged but should defer to the experts.

TVA: It’s interesting to note that we are transitioning from school choice, to course choice, to experience choice—a new era where each learner will have customized pathways guided by algorithms, advisors, and learner choices. Add lots of anywhere anytime learning options and the engagement challenge shifts from where to build the next $100 million high school to how to scale quality guidance.

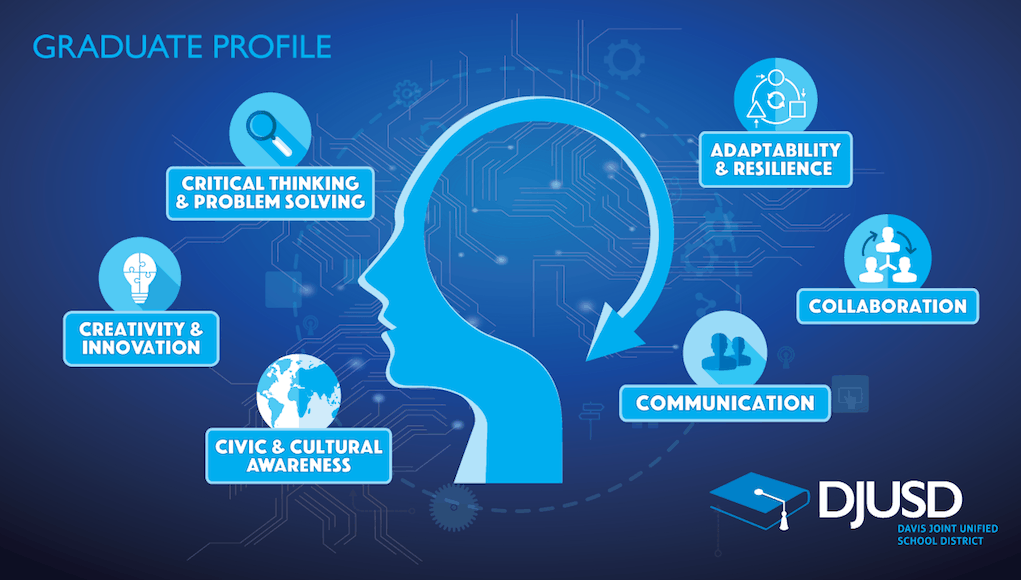

KK: I found your keynote on the implications of AI compelling and provocative. How would it impact your view of what should be in a district or school’s portrait of a graduate? So, if most districts are using the 4 Cs as the starting point, what would you recommend that they do to refine it based on their taking your AI concerns and reflections into consideration?

TVA: I interviewed Michael Fullan recently and he made two friendly amendments to what he calls “life readiness” rather than college and career readiness. He adds character and citizenship to collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking. I think those are great additions, but communities will have different ways of expressing them as priorities.

Collaboration is more important than ever. The application most important is the ability to lead a diverse project team to a defined goal. That adds leadership and project management to success skills.

Young people will face a lot more novelty and complexity than we did. As I wrote with Jonathan Rochelle from Google and Katherine Prince from KnowledgeWorks, “What we most desire for young people is confidence in the face of complexity.”

Design thinking, popularized by the Stanford Design School, is a structured approach to facing complexity. Potential solutions are prototyped and improved through iteration. Computer scientists use a similar approach to design called computational thinking (see how South Fayette schools teaches it). Design skills should not be relegated to a coding class; it should (like writing) be integrated across the curriculum.

KK: Is critical thinking still a good frame, would you use a different term, or would you just make sure that complex problem solving, numerical literacy, design thinking, and systems thinking were essential elements of critical thinking?

TVA: Critical thinking is more critical than ever, but it’s so packed with multiple meanings, it’s hard to assess across the curriculum. It is important to break it into component parts. Minerva, a new university based on learning science, makes “thinking critically” one of four core competencies but they break it down into “evaluating claims, analyzing inference, weighing decisions, and analyzing problems.” This breaks down into more than 50 specific concepts and habits that are assessed in socratic seminars and projects (more than half of the total).

KK: Given your thoughts about “free agency” would you be more explicit about “self-direction” as a 21st-century competency?

TVA: The Nellie Mae Education Foundation says “Student-centered learning engages students in their own success—and incorporates their interests and skills into the learning process. Students support each other’s progress and celebrate success.”

Our friends at New Tech Network assess student agency in every project. They explain, “We help students see effort and practice in a new light and associate both as growth paths and, ultimately, success. We can provide students with the skills to rebound from setbacks and build confidence as they welcome new challenges. Instilling the principles of “agency” helps students find personal relevance in their work and motivates them to participate actively, build relationships and understand how they impact themselves and their communities.”

KK: Self-direction is a very important concept to me and I am not certain it is adequately covered within “student agency” or “student-centered”. In my view, “student-centered” and “student agency” are strategies that educators use to steer education in the right direction. But self-direction is a competency student themselves need to aspire to. I often get asked where “work ethic” belongs in the portrait of a graduate and I contend it is a 20th Century concept. When we were growing up work ethic was a critical skill but it was often under somebody else’s direction. In the “flat” world each person must be able to independently direct their own work wherever they sit in the organization or whatever context they are in. It is not enough to be open to doing more; you yourself need to determine what is the best next step. “Student agency” and “student-centered” may lead to more contexts that require self-direction, but self-direction itself needs to be aspired to and honed as an essential skill by students.

TVA: That’s a great distinction. I think the MyWays outcome framework from NGLC does the best job of describing these self-direction capabilities as Habits of Success (self-direction, perseverance, positive mindset, and learning), Wayfinding Abilities (e.g., surveying, identifying opportunity, developing plans, finding help, and navigating) and Creative Know How (e.g., entrepreneurship and practical life skills).

Because most high school graduates will enter the freelance/gig economy or manage their careers as a series of projects, everyone will be an entrepreneur in the new economy. Taking initiative to spot an opportunity, pursue partnerships, and deliver value will be critical for success.

Because most high school graduates will enter the freelance/gig economy or manage their careers as a series of projects, everyone will be an entrepreneur in the new economy. Taking initiative to spot an opportunity, pursue partnerships, and deliver value will be critical for success.

The key to answering the “What should grads know and be able to do?” question is community conversations that shape a high-level vision (a grad profile) and some detailed work to turn those into meaningful and measurable learning objectives.

For more see:

- Measuring What Matters

- Measuring What Matters: A Framework Review

- It’s Time to Update Your Graduate Profile – Here’s How (podcast ft. Ken Kay)

This post was originally published on Forbes.

Stay in-the-know with all things edtech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.