Developing Self-Directed Learners

By Tom Vander Ark and Emily Liebtag

“I haven’t met many self-directed teenagers,” said a frustrated high school teacher during a recent presentation.

As we contemplate the vast problem of teenage disengagement and the apparent low level of self-direction, we have to ask, “Is it our kids or our schools?”

We’ve seen enough high engagement schools where most teens were self-directed to suggest that it may be the design of American secondary schools that’s the problem—not the kids.

For a century, the primary design meme of American schools has been compliant consumption. Students read, practice and regurgitate in small chunks in siloed classes in regimented environments. Low levels of self-direction shouldn’t be surprising—it is inherent in the traditional secondary school design.

High engagement schools start from a different conception—knowledge co-creation and active production. They design a very different learner experience and support it with a student-centered culture and opportunities to improve self-regulation, initiative and persistence—all key to self-directed learning.

Why Does Self-Direction Matter?

Growth of the freelance- and gig-economy makes self-direction an imperative, but it’s also increasingly important inside organizations. David Rattray of the LA Chamber said, “Employees need to change their disposition toward employers away from work for someone else to an attitude of working for myself—agency, self-discipline, initiative and risk-taking are all important on the job.”

Many adults are working in roles where they need to be more independent and efficiently manage their own time, often through a series of projects. Employers are looking for candidates that on their own are able to identify a driving question, determine a team they need to help answer that question, able to effectively work with that team, execute and manage the project—through multiple iterations with lots of feedback—and then reflect and evaluate their work. Students should be developing self-direction by learning in the same way.

Where To Start

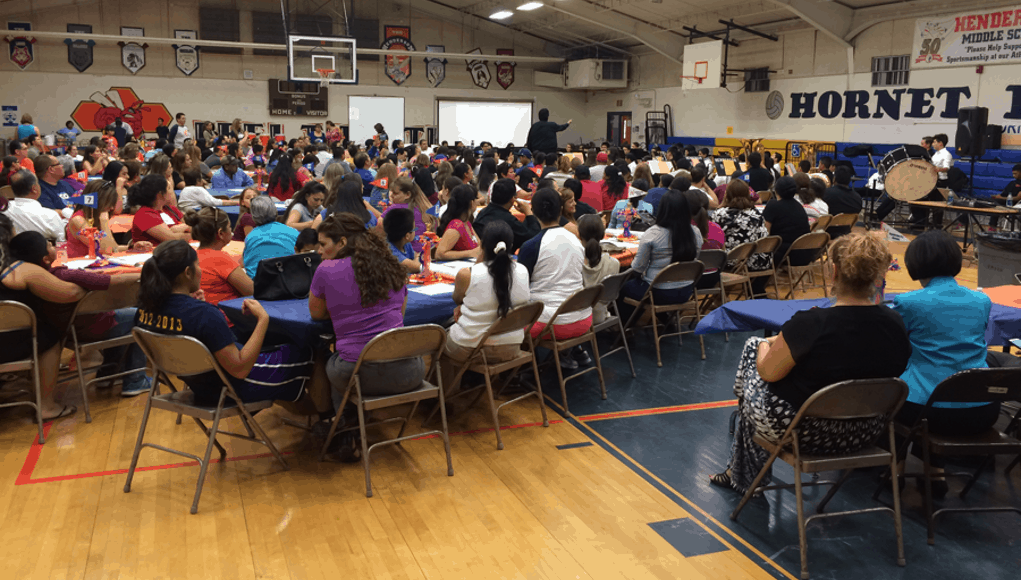

Wondering how to make self-direction a priority? Hold a community conversation about what graduates should know and be able to do—agency, initiative and self-direction always rise to the top. Community conversations, like those in El Paso, Houston, and Marion, Ohio, resulted in student agency and self-direction becoming priority outcomes.

If you’re a teacher or parent, you can ask good questions rather than provide simple answers; you can help students use a to-do list, develop a personal learning plan and a portfolio of their best work.

If you’re a principal, you can propose an advisory period to promote self-direction and other success skills. You can make time in the schedule for more self-directed work. For example, Singapore American School added makerspaces, a genius hour and independent study courses to encourage students to pursue self-directed learning.

You can work around the edges and improve self-direction within a course or by making a little time in the schedule, but we really believe that developing self-directed learners as a core objective requires dedicated time and tools, a student-centered culture and a new approach to learner experience.

Skills & Tools

Don’t assume students have learned self-regulation, time management and project management. They all take instruction, practice and reflection. Students need guides, supports and cues to help as they work in both on- and offline environments. Students at Redwood Heights Elementary School often use ‘have-to’ checklists where they are guided through tasks they must do and then get to choose additional activities when they are finished. They learn to self-manage their time and how to check-in when they know they need support.

A strong advisory system creates a focus for social emotional skill-building, a touch point for conversation, and home for personal learning plans and portfolios. Chris Lehmann, head of Philadelphia’s Science Leadership Academy (SLA), believes that student-teacher relationships radiate from the advisory period. “Think of advisory as the soul of your school. And in everything you do, remember that you teach students before you teach subjects. Advisory is the place in the schedule where that idea has its core and then it spreads into everything else we do,” Lehmann said.

Student ambassador program, like the one at Katherine Smith Elementary, promote metacognition about what students are learning. With a little coaching, Smith students are self-directed in the process of leading visitors around their school. A period of reflection after the visit helps them observe growth and prepare to do even better next time.

Culture

A compliance culture—hall passes, bell schedules, regimented behavior and punishment focused discipline—dampens self-direction.

Many urban districts and school networks like YouthBuild have adopted restorative justice practices that help students build positive solutions rather than suspending them from school.

Students at Huntley High outside of Chicago earn the right to work independently on and off campus.

Experts say culture is the most important issue to get right in a new school. “Think about how to help students acculturate themselves to your learning environment,” said Alex Hernandez of Charter School Growth Fund, which has supported more than 500 new schools. “Will there be a bootcamp or other introductory experience? How do you want to set the tone around student voice, student agency, joy, etc. To borrow the popular phrase: culture eats strategy for lunch.”

At Olin College, students apply design thinking from day one—shaping projects and solutions. Professors engage students in course redesign when it doesn’t go as well as planned. Upper division students shape semester-long solutions to global challenges.

Schools that are firm on expectations and principles but flexible on pathways give students time to engage deeply and opportunities to succeed and fail, and support the development of self-direction.

Learner Experience

The learner experience is crucial when it comes to designing environments where students can learn to be self-directed. Here are four things educators should consider:

- Autonomy & Responsibility. Are students doing work that they have ownership over? Or is it just the textbook put into a different form. What is the task? Does it make sense for students to do on their own? What are the desired outcomes? Be sure students know the outcomes and how they can scaffold their own learning to progress towards meeting them.

- Complexity. What are students being asked to do? How much of the work can they feel successful doing on their own and what percentage of the task do they need support with. Find the sweet-spot between challenge and students feeling successful.

- Duration. How much time on task are students already consistently demonstrating? How much time have students spent learning content or skills to prepare them to work independently? Teachers need to think about having a mixture of short and supported experiences as well as some that are more long-term and independent. This will increase students ability to sustain self-directed learning.

- Voice & Choice. Students need to feel like they have voice and choice in their learning and environment. This means time for interest based learning, opportunities to shape assignments and deliverables and choice in how they showcase what they have learned. When students and teachers co-construct projects, they can be interest-based and packed with important learning targets.

Like writing and problem-solving, self-directed learning is a progression—the combination of knowledge, skills and mindsets deployed in different environments toward different aims.

Like writing and problem-solving, self-directed learning is a progression—the combination of knowledge, skills and mindsets deployed in different environments toward different aims.

Students that haven’t built the muscles of self-direction in middle grades often flounder initially in a project-based high school that demands a high degree of self- and project-management.

Ideally, self-direction should be developed on a continuum from preschool to independent postsecondary learning. The expectations, environment, scaffolding and supports should reflect increasing degree of self-direction.

For example, take an earth science project. While a third grader may in fact be ready to manage a project by himself/herself, consider the following progression of self-directed learning:

| Level | 3rd Grade | 7th Grade | 11th Grade |

| Autonomy & responsibility | Classroom work | Independent field trip, some work at home or off-campus | Must complete some work off campus or in a field-experience |

| Complexity | Specific target (origin of local rock formation) | Broad topic (Understanding plate tectonics) | Interdisciplinary (planning megacities in seismic zones) |

| Duration | 3 day project | 3 week project | 3 month project |

| Voice & Choice | List of 5 choices | Student options on public product | Student frames project and deliverables with advisors |

| Management | Students manage teacher-framed tasks | Student manages project with daily check in | Student manages project with 6 advisor consultations |

We know that self-directed learning is personal and contextual. Some students might feel confident working on an earth science project independently, while in another subject they aren’t yet ready for extended periods of self-directed time on task. A student may flourish in an outdoor place-based learning experience but struggle in with attending in a classroom setting.

Self-directed learning needs to be taught across the curricular areas and throughout the school day. Self-direction is applicable and can be developed in all subject areas. Every educator, whether they are teaching calculus or coding, can help to promote more self-direction in students.

For more, see:

- Preparing Teachers for a Project-Based World

- Novelty and Complexity: 13 Youth On-Ramps

- 3 Reasons To Expect the Unexpected…and What To Do About It

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update. This post includes mentions of a Getting Smart partner. For a full list of partners, affiliate organizations and all other disclosures, please see our Partner page.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.