Empowering Girls to Become Future STEM Stars

To help inspire today’s female students to discover their passion for a STEM career, multinational energy corporation Chevron and Techbridge Girls, a nonprofit program that helps support young girls interested in STEM, have teamed up to work on reversing this trend.

I had the opportunity to interview Blair Blackwell, manager of education and corporate programs at Chevron, and Nikole Collins-Puri, CEO of Techbridge Girls, about why this issue still exists today as well as recommendations on how we can all help empower the next generation of female STEM leaders.

Why do girls’ beliefs, motivations and aspirations begin changing in fourth grade, causing this decline in STEM interest to happen? What is serving as a barrier at this age?

Blair: We know that research shows students decide as early as second grade whether they are good at and whether they like science, technology, engineering and math (STEM). Many times, young girls in elementary school face implicit biases from their teachers, parents, media and even peers. They grow up thinking that STEM is for boys and can become discouraged from STEM subjects.

We also know from research that girls prefer subjects where they can see the impact they are making in the world, which is why it’s important early on to underscore the impact STEM can have on the community. Overall, we need a cultural shift where we learn to nurture and support girls in STEM the same way we tend to do for boys.

Nikole: My organization, Techbridge Girls, inspires girls of color from low-income families to discover their passion for STEM. Through our gender and culture responsive after-school and professional development programs, we empower the next generation of girl innovators and leaders to change the world.

We recently published a white paper that provides best practices to encourage girls in STEM education and careers. The white paper found that we need to apply a girl-centric and culturally responsive design process for recruiting and retaining girls in STEM and strengthen the STEM ecosystem where students, families, educators, role models and the STEM industry are doing their part to move our girls toward a path of STEM success and leadership.

Why are girls even more inclined to leave the STEM pipeline after calculus?

Nikole: There are many reasons for this. For example, especially in middle school, girls begin to understand who they are in the society—popular, pretty, what’s cool and what’s not, and often STEM is on the negative side of those perceptions. We also have to manage that girls often feel that if it’s not perfect, then it’s not good enough. In an industry that sees failure as a necessary component to the process, it is important to shift the mindset of girls so that failure is looked at as a positive path toward “perfection.”

Part of our program is focused on helping girls become more comfortable with building on mistakes. We actually praise our “glorious goofs” after every program session to show how important it is to celebrate this critical aspect to the process. We make sure our girls know that it is more important to learn from the process than strive for perfection.

Blair: And recently, an NSF study analyzed students with above-average mathematical abilities who were interested in STEM to determine if they would continue in STEM after taking a college calculus course. The study found women were 1.5 times more likely to be dissuaded from continuing in calculus than men.

Women expressed concerns that they did not understand the course materials more than men, and ended the term with “lower mathematical confidence than men.” The study notes that it isn’t ability, but confidence that affects whether they persist. This is why it’s important to have organizations like Techbridge to help build girls confidence early on.

What should STEM “look like” in the classroom to keep girls interested? How do you customize design solutions there?

Blair: While the classroom is one piece of the puzzle, as Nikole noted before, we need to change the STEM ecosystem. Some ideas for customizing design solutions to better engage girls include:

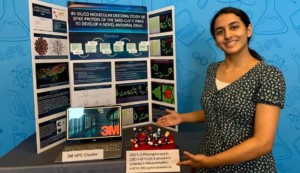

- STEM recruiting, resources and programs should focus on girls’ potential to transform society through STEM.

- Use real-world scenarios in curriculum to allow girls to see the value and impact they could be making through engaging in STEM courses and eventually STEM careers. For instance, the National Academy of Engineering Grand Challenges can serve as a great resource to inspire girls in how they might address global issues such as health, infrastructure and sustainability through engineering.

- Design girls-only “safe spaces” for students new to STEM that can empower girls to fill every role on an engineering team. An environment like this offers girls a place to learn from each other and to build confidence to learn and grown in a STEM-focused space.

How might we help girls have more confidence in their STEM abilities? What are some best practices for starting this?

Blair: The key to helping girls have more confidence in their STEM abilities is to ensure they have solid role models, mentors and communities to teach and encourage them. Role models can have a dramatic impact on girls’ interest in these fields and, to some extent, their persistence in sticking with them and advancing.

When I was growing up, I wanted to be a biologist, but because I lacked strong STEM role models, I dropped out of the STEM pipeline right between high school and college. Now, through my work to increase STEM access for girls and young women in America, I know my experience is not unique.

We need more programs to help girls identify and form relationships with female role models, mentors and sponsors who can encourage their interest in STEM and eventually pave the way to a STEM career.

Nikole: For example, we pair girls with role models because we believe if you can see it then you can be it. Our role models come from various STEM careers and we train them so that they are able to translate their everyday work into something that is relatable, engaging and applicable to what our girls are learning in the program and experiencing in their everyday life.

Girls not only need advocates at school and in the workplace, but also at home. Our research found that girls are twice as likely as boys to look to their parents for college and career advice. We also need to demystify STEM for parents so they can continue to encourage girls once they leave our program.

Arming parents with resources on STEM careers and involving families in the design of programs—regardless of their backgrounds—will keep their daughters inspired and excited about STEM education and careers.

How do we go about helping parents, policymakers, educators and the education industry to make connections between STEM and females?

Nikole: As Blair mentioned, we have to be thoughtful and deliberate in recognizing that we often demonstrate an implicit bias that STEM is for boys. We therefore need to be very intentional in creating re-designed, girl-centric resources if we want to change the game for girls in STEM, especially girls of color. The private sector must shift their behavior and implement practices that will retain and advance girls toward STEM, walk the talk, and partner with community-based organizations that are deeply connected to the populations that are under-resourced and often left out of the pool of opportunities that these great organizations provide.

Blair: Nikole raises an important point about the necessity of engaging a variety of actors, and there is great power in partnerships. The key to increasing girls’ engagement in STEM is through a collective effort from the private sector, foundations, STEM education providers and government. We must commit to working together to inspire girls to not only pursue STEM education, but to stick with it.

For more, see:

- Getting Smart on Learner-Centered STEM

- Every Student is a STEM Student

- 12 Ways to Start Teaching STEM in Your School

Blair Blackwell is the manager of education and corporate programs for Chevron. Follow her on Twitter: @blairblackwell

Nikole Collins-Puri is the CEO of Techbridge Girls. Follow her on Twitter: @NiKoleCPuri

Stay in-the-know with all things EdTech and innovations in learning by signing up to receive the weekly Smart Update.

Austin Saunders

I like what you said about shifting the mindset in middle school-aged girls to accept failure to get them more involved with STEM. My wife and I want to make sure that our daughter is able to follow any dream that she has in the future. We'll be sure to look into our options for helping her see failure as a necessary part of the learning process in the future.

Vivian Black

I was very interested in the ways resources out there can empower girls. It is interesting how girls' beliefs, motivations, and aspirations begin changing as early as fourth grade. Female empowerment organizations are vital. https://musetogetherinc.com/