The Case for Boundary Breaking Education

Twice daily, the moon pulls more than a cubic mile of the Pacific Ocean into the Puget Sound. The sea travels 50 miles past the ports of Seattle and Tacoma where the tide raises an average of eight feet against aging piers, sea front restaurants, and the bulkheads of expensive homes. It travels another 50 miles, grows to 14 feet in amplitude by the time it reaches Olympia creating currents of six knots, flooding into hundreds of inlets, bays, and forgotten tidal flats where the boundary between land and sea is far less distinct. The sea returns in unrelenting 11 and a half hour cycles to grasslands and rocky flats.

Creeping into Rocky Bay in the south Sound, the sea meets a small creek in quiet collisions and swirling whirlpools. The same, yet different, the freshwater attempts to hold back the sea, but in a quiet reversal of fortunes the creek gradually widens and becomes a saltwater bay covering oysters, clams and geoducks. The force of the wind and the tide rearrange things for inhabitants; the bay empties six hours later leaving a fresh imprint on the beach.

Living on the Sound is a constant reminder of the rhythm of the spinning planet we share. It is a dynamic, thin, fragile ecosystem that reflects the health of life in the sea and on land.

Like tidal spaces, it’s the space between sciences, countries, systems, and people that is most interesting. These boundary spaces are where conflict, innovation, and learning most frequently happen.

Boundary spaces. Our social spaces are marked by dynamic boundaries between

- Nations: a history of power and conflict hyped by the global economy;

- Rich and poor: expanding technology-powered income inequality;

- People and the environment: communities extracting benefit from the environment;

- Right and wrong: negotiated rules are replacing traditional absolutes;

- Mercy and justice: polarized politics pit access and opportunity against liberty and responsibility; and

- Public and private: the social self and negotiated privacy.

In science, it’s often the space between disciplines that yields important developments. For example:

- Chemistry and molecular biology: screening molecules that activate bio-pathways

- Ecology and evolutionary biology: the history and future of biodiversity

- Big data and genomics: biological process modeling and mapping

- Engineering and biology: regenerative health solutions

- Machine learning and cognitive psychology: the tutor that learns you

Each of these represent an emerging opportunity set. But it’s also true that revolutions in science often come from the study of seemingly unresolvable paradoxes. “An intense focus on these paradoxes, and their eventual resolution, is a process that has leads to many important breakthroughs,” according to a leading physics blog.

In education the most interesting developments are at the boundary of:

- Interest-based and standards-based learning: student-driven learning that results in development of important knowledge, skills, and dispositions; and

- Organizational and technology development: SNHU’s College for America and Summit Public Schools are great examples of designing new learning environments and platforms simultaneously.

Everything is changing—just not at the same rate. Modern societies are strained by science and technology advancing moving more quickly that social norms and civic structures—a boundary problem of caused by differential evolution. Our public institutions find themselves ill equipped to deal with rapid and complex problems and more frequent unpredicted “black swan” events. Fueled by money and media, American politics are increasingly focused on short-term results instead of long-term investments and sound bites rather than public dialog.

Creating nimble government and social responses requires leadership across boundaries, partnerships across boundaries, and learning across boundaries.

Boundary breaking education. Few young people are being prepared for the world they live in and will inherit. Few get the opportunity to be immersed in complex systems or construct investigations into multidimensional problems.

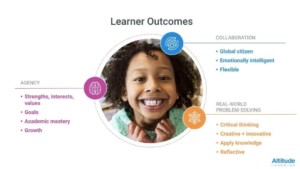

The Hewlett Foundation promotes deeper learning—experiences that help students develop and use knowledge and skills in a way that prepares them for a complex world. The deeper learning framework describes six competencies:

- Master core academic content

- Think critically and solve complex problems

- Work collaboratively

- Communicate effectively

- Learn how to learn

- Develop academic mindsets

The boundary breaking kinds of environments and experiences that produce these competencies are compared to traditional education below:

| Traditional | Boundary Breaking |

| Discipline-based courses | Interdisciplinary projects |

| Teacher-driven instruction | Student-driven learning |

| Turn it in compliance culture | Publish and present culture |

| Memorizing and test taking | Marketing and project management |

Before they graduate from high school, young people should have the opportunity to experiences success in college, several work settings, performing arts, and community service. They should lead a team, publish professional quality work, and leave with a curated portfolio of work.

The first chapter of our recently published book, Smart Cities that Work for Everyone, suggests that these experiences lead to an innovation mindset—an appreciation that effort, initiative, and collaboration are critical dispositions in a dynamic work.

For more, ready about the design for Boundary High School and Preparing Leaders for Deeper Learning.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.