Why We Need a Moratorium on Meaningless Note-Taking

Over the years, as I have encountered a goodly number of teachers who have complained vociferously about their students’ lack of proper note-taking skills, I have found myself more and more befuddled. Dare I tell them what I really think, that they are wasting their students’ time and setting them up for failure by having them outline their lecture notes, word for word, from the over-crowded PowerPoint slides they’ve projected at the front of the classroom? That students don’t understand the point of taking notes for something they can Google anyhow? That, instead, students should learn how to take purposeful notes from field observations or experiments, or they should write notes that cull information from a vast array of resources? That we need to create opportunities for mastering the 21st-century skills of information curation, not of hand copying the anointed word like so many monks in their ivory towers?

The last time I went out on a digital limb like this, declaring the end of something, I stirred up a lively discussion about the death of the five-paragraph essay. I suspect I’m going to do it again in this post as I call for a moratorium on meaningless note-taking.

A Pet Peeve and a New Skill

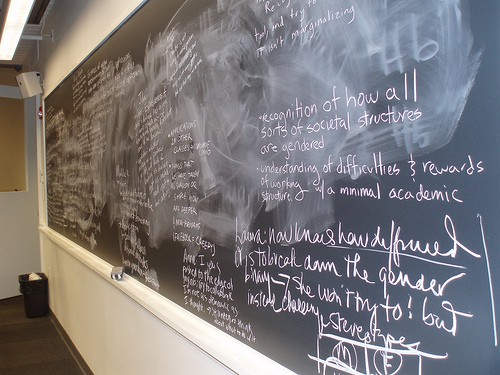

A decade or so ago, I used to watch, somewhat mystified, from the hallway as one of my more seasoned colleagues meticulously copied his U.S. History lecture notes in his curious boxy handwriting onto the chalkboard. His students, who were much better readers of cursive writing back in those days, would squint and do their best to copy his notes in their own messy handwriting into fat notebooks, which they would then memorize for killer tests based on their ability to regurgitate content. Then my esteemed colleague would erase his carefully chalked notes and start all over again.

At the time, I accepted the commonly held notion, now debunked, that copying down lecture notes reinforces learning. But this kind of note-taking activity seemed senseless to me even then – why not photocopy the notes for the students, I thought, and at least save yourself a lot of painful recopying of the same stuff from year to year?

My distaste for mind-numbing note-taking sessions has grown over the years. We have so much we need to do with our students, I lose patience with how teachers squander time and their students’ attention in this way. Worse, these teachers put their students at risk of learning inevitably miscopied information that cannot accurately portray their true learning of a subject.

Instead, students should be learning note-taking as a way of organizing data and curating information they need for a defined purpose. Students should sift and cull, summarize and synthesize. Students should learn how to take notes in ways that correlate with real-life situations. Finally, students should master the skill of making meaning from their notes and finding the best ways to share that meaning with others.

Note-taking should have an authentic purpose.

After high school and college, when do we take lecture notes in real life, after all? On the back of an envelope from a phone call? In a list of “to-dos” from a meeting? As a summary of information – whether provided orally or in print – to be shared with others?

When does our note-taking have a real purpose? When we are collecting field notes, listening to a webinar or YouTube training video, scanning a book for nuggets of wisdom. When we attend workshops or conferences, or even when we meet someone for a networking lunch.

A quick perusal of the vast numbers of college websites dedicated to teaching note-taking skills forces me to accept that we must prepare those students who still must sit through hour-long lectures. This is a practical skill students do need, but in the age of online learning, for how long?

What are the actual skills students need in order to organize the vast amounts of information they must cull through to make meaning and solve problems? Is note-taking from the Internet, from Twitter, or from texts really a different kind of animal? Won’t students buy into the note-taking process if they understand that it matters for something more than spitting back a professor’s lecture notes that haven’t changed in the last twenty years?

Note-taking should be the beginning, not the end, of knowledge curation.

Taking lecture notes, the most common note-taking activity I witness, is an end point. The teacher has used his or her years of taking notes from college lectures, reading in textbooks, and independent research to summarize key facts or points for students to ingest. I have a theory that teachers do this because students refuse to read the boring textbook (another issue), so the teacher digests it for them and then conducts a forced walk through the material. Many teachers, unfortunately, think this is what they are supposed to do; sadly, they think it’s what teaching really is.

But they’ve got things totally backwards.

Students need to be gathering the information from sources and close observation themselves. Part of this may involve traditional note-taking skills to summarize and synthesize material in succinct, sharable chunks. But a more important skill involves sifting through the information itself, selecting the most important elements, and organizing it in a way that makes sense. That’s where the learning really happens. If the teacher does all of this up front, then what is the student actually supposed to be learning other than what a traditional outline looks like and a bunch of facts that will have to be upchucked on a test?

Note-taking should be interactive and absorb multiple formats.

Now, I see nothing wrong with teachers providing their own brief notes of certain background points to provide a jumpstart for their students’ forays into deeper investigations. This can actually save valuable time, as well as provide important modeling of how to summarize, how to select key points, and how to arrange information to group ideas or concepts. But at the very least, such notes should include hyperlinks, should be posted in a shared digital space, and should be open to amendment and annotation by the students themselves.

Likewise, we need to think of note-taking as something more than the traditional Cornell style. Note-taking should include brainstormed lists, diagrams and drawings, photographs, and other artifacts of learning. We should rethink note-taking not as outlined material for the test, but as blogs, wikis, backchannels, discussion forums, and status updates. The form of the notes should suit their purpose; the tool for taking the notes should do so as well.

Note-taking should be shared.

Although we may take notes for individual purposes now and then, it is much more likely these days that we would collect notes for a common purpose or project shared with colleagues. Google Drive has made the means for doing this as ubiquitous as email, so why aren’t more classes embracing the idea of collective and collaborative note-taking?

Making our notes public means we are more accountable for their content – and others will surely correct us if their learning is at stake as well. This kind of sharing can also be the nexus for learning to be transparent, another 21st-century skill, as we honestly put forth what we know and what we don’t know, providing the basis from which we can ask questions, learn from one another, and innovate.

Isn’t that how professionals build knowledge together in the real world?

A Challenge

I know that old habits die hard. I only want to challenge teachers to think about how they really want to spend their precious time with their students. Can we find ways to teach meaningful note-taking in our classes? Can we give this skill the attention it deserves by thoughtfully constructing lessons that incorporate note-taking in authentic ways with the best tools for the job?

I’m excited by the opportunities for inspired note-taking suggested by the iPad app Notablility and its syncing ability to Dropbox, by Sky Pens and their connection to Evernote. We still have plenty to explore about the best practices for collecting and sharing information in Diigo or via Livebinders.

If we stop doing the students’ work for them, maybe we’ll have time to reinvent note-taking for the digital age.

Photo Credit: lorda via Compfight cc

Jeremy Greene

I think this gets it wrong.

And the study linked does not say anything about note-taking - does it??? Or were you writing about summarizing from a book? So the debunking link misses the mark.

In the business world, I took notes at meetings. I still take them at faculty meetings for things to remember. Remembering things is vital - see E.D. Hirsch for this.

In history classes your notes should be different than the textbook - so good point there.

It might not be note taking, but the key is how do you retain things said to you whether in a meeting, on a lecture, on-line (I am taking Coursera courses right now - many students state they are taking notes).

And the argument that we are taking notes to share underlines the fact that it is important to take good notes!!!

A wiki is one way. But I fiind at the high school level, yes, I've tried it. That everyone goes with the minimum. And forced requirements on the wiki are anti-wiki to me.

Lastly, I don't get the doing it for them. The key is to write a few things, have visuals and videos as needed and have students get what you SAY. DO NOT WRITE EVERYTHING. Again the key is how do you retain things said. Writing them down seems to work. Why we know what Socrates probably said and don't know anything any Australian aborigine said...

My thoughts...

Susan Davis

Thanks for your feedback, Jeremy. In the original study from Psychological Science in the Public Interest, summarizing and note-taking are closely linked. Both still rank low, as far as reinforcing learning is concerned -- which is noted in the article I link to.

This passage from the original study goes to the heart of the issues I raise here: "summarization and note-taking were both more beneficial than was verbatim copying. Students in the verbatim-copying group still had to locate the most important information in the text, but they did not synthesize it into a summary or rephrase it in their notes. Thus, writing about the important points in one’s own words produced a benefit over and above that of selecting important information; students benefited from the more active processing involved in summarization and note-taking (see Wittrock, 1990, and Chi, 2009, for reviews of active/generative learning)."

Thus, the distinction between meaningless note-taking and purposeful synthesis.

Samuel Hollis

Hi, I am currently a student at Cal State Northridge and completely agree with you. Could you point me to more resources about this topic? I'm currently looking for note-taking techniques with digital media. In my search I came across ideas such as my basic skills in note-taking are not efficient enough when taking notes digitally such as Onenote. I had no clue that was even a thing until after unsuccessful semesters at school. In theory, Onenote seems perfect. But in practice, it hasn't been and I use it on a tablet(and phone) with pen input so that's not the problem. I've been learning that there's different ways of taking notes and these different ways effect how one learns. I got this idea from Mitchel Resnick in this video: http://serious-science.org/videos/761

Anything to help me out?

Susan Davis

Samuel,

I think it's important to assess each situation and find the right tools for that particular purpose. Sometimes teachers will provide digital notes for their students to annotate. Sometimes students find ways to create collective notes in a Google Doc or some other shared space. The bigger question becomes "what purpose do the notes serve?" There's a difference between taking notes for a particular purpose and taking meaningless notes that are just meant for regurgitation on a test (though the latter is a purpose we unfortunately force students to live with).

Good luck!