Can We Ditch AP for More Engaging Courses?

Key Points

-

Offering AP courses can be an important part of a school’s value proposition to learners, families, and the community.

-

Replacing them with more engaging alternatives requires a community agreement around a new value proposition–and that typically takes a lot of time and effort.

-

Below are six tips for education leaders thinking about how many AP classes to offer and what alternatives to consider.

A school administrator asked me if he could drop all or most of their school’s Advanced Placement courses in favor of more experiential courses. (Revealing the bias of both parties, he asked the question at a conference on real world learning.) The answer is yes, but…

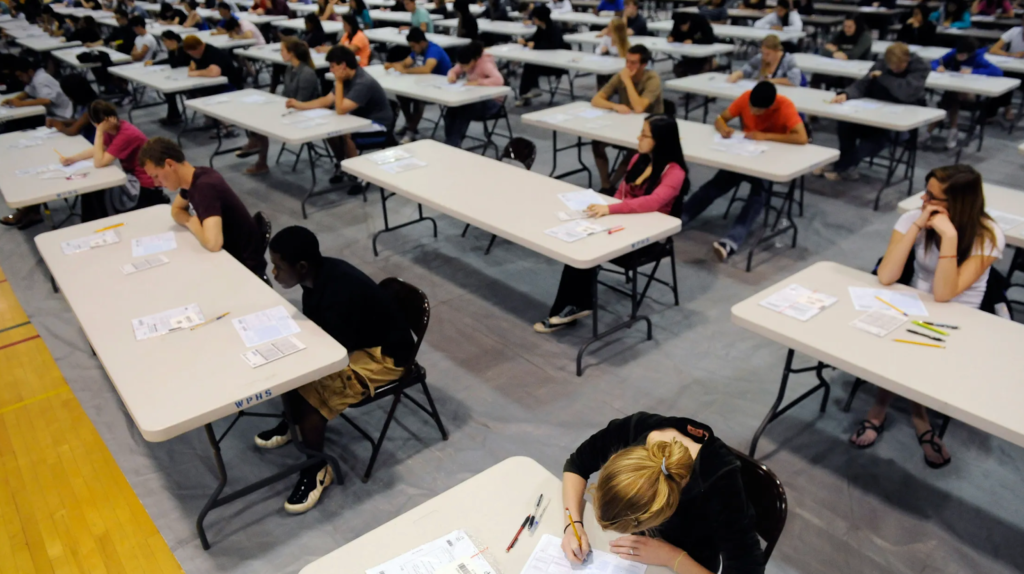

About 1.2 million students took more than 4 million AP exams in 2020. With a score of 3 or better (on a scale of 5) many colleges will accept some AP courses for credit making them an attractive and affordable way for students to get started earning free college credit or to boost chances of enrollment in selective universities (where they’re not likely to grant credit).

Offering AP courses can be an important part of a school’s value proposition to learners, families, and the community. Replacing them with more engaging alternatives requires a community agreement around a new value proposition–and that typically takes a lot of time and effort.

The World is Changing Faster Than AP

The market value of AP classes lies in the consistency of the big paper and pencil end of year test. The downside is that these tests encourage cramming and regurgitating facts. It’s an outdated testing model that encourages an outdated content-focused pedagogy that, with each passing year, grows further out of step with what young people should know and be able to do and what powerful learning can be.

The International Baccalaureate system is a comprehensive K-12 course of study that requires more reading and writing than AP. The high school Diploma Program includes a beneficial theory of knowledge class, a 10th grade project, an extended essay, and service learning. But, like AP, the IB Diploma Program relies primarily on end of course exams for quality assurance.

Neither IB or AP leaves much room for individual explorations or community connected projects. Neither encourages collaborative projects using smart tools. Both encourage cramming for tests that don’t benefit learners or teachers with feedback.

AP and IB offer the benefits of consistency and recognition but their relevance and value will continue to erode throughout this decade. As a result, school leaders can’t put off the question of whether and how much they rely on AP or IB for long.

While context matters a lot, following are six tips for education leaders thinking about how many AP classes to offer and what alternatives to consider.

1. Given Diminishing Returns, Offer Fewer AP Classes

Some parents assume that admissions into selective colleges requires a transcript packed with AP courses but there are limits to the benefits. The Singapore American School used to offer every AP course and routinely had students graduate with a dozen or more AP classes. After interviewing a hundred college admissions officers, they found diminishing returns after five or six AP classes. And, many schools limit the amount of credit they will accept from AP courses.

2. Choose Useful Classes with Updated Tests

College Board has updated some of its 38 AP tests to encourage classes that are more engaging and relevant. One example is AP CS Principles, a good introduction to Computer Science that all students would benefit from while the old AP CS class is a Java programming class of some value for those interested in careers in web development but less broadly applicable, particularly for young people interested in data science. All Sophomores at Washington Leadership Academy take AP CS Principles as part of a coherent four year CS course sequence.

3. Offer Project-Based AP Classes

Research suggests that teaching AP classes using a project-based approach produces better results. The project-based Knowledge in Action program, developed by University of Washington researchers, showed improved results on AP exams in AP U.S. Government and AP Environmental Science.

Some schools teach AP courses in integrated project-based blocks. Crosstown High in Memphis combines AP Geography and English in a block that empowers students to select local problems to study and to address with proposed solutions. Some schools block AP U.S. History and AP English Literature and Composition and incorporate integrated projects.

4. Consider Dual Enrollment Courses

Most states have provision for dual enrollment courses that count for both high school and college credit. These may be offered in high school by a college certified instructor or at a community college. Some states fund dual enrollment (while a few require student payment for college credit) and ensure credit transferability between state institutions. Where funded, transferable, well taught, and a part of a coherent pathway, dual credit courses can be preferable to AP courses. Dual enrollment may come with the added benefit of study on a college campus and experiencing success in what’s next.

Neither IB or AP leaves much room for individual explorations or community connected projects.

Tom Vander ARk

5. Consider Applied Alternatives and Start with a Microschool

Well regarded diverse public schools of choice like High Tech High have long offered challenging project-based courses instead of AP or IB courses. Decades of compelling exhibitions of student work and student success in higher ed led to a strong reputation with selective colleges.

A school offering AP or IB courses with a history of graduates admitted to selective institutions has some flexibility to replace some of those courses with dual enrollment courses or internally developed experiential courses after engaging with stakeholders.

For a high school without a strong reputation to move away from known standards of quality would require making the case to parents and learners that experiential courses could be taught consistently well and would better enable students to achieve the school’s learning goals.

A transition away from a high school curriculum dominated by AP or IB can be initiated by demonstrating the benefits of team taught project-based learning in an academy or microschool.

For example, EDGE is a global studies microschool opened in 2021 in a converted wing of Liberty High School, a well regarded comprehensive high school north of Kansas City.

6. Start Working on New Signals

With many colleges going test optional, there is an opportunity to equip learners with new forms of evidence (with or without AP classes) including a portfolio with artifacts of learning and a Linkedin profile complete with work experiences and endorsements.

Credentialed skills and experiences (such as client projects, internships, and entrepreneurial experiences) will become valued signals in the second half of this decade. Digital credentials and learner records will reduce dependence on traditional signals (GPA, class rank, and AP scores).

Conclusion

Replacing AP (or IB) with more experiential courses requires a new bargain with the community, one based on clearly defined goals, perhaps illustrated by demonstration, and with a commitment to consistently strong execution.

If the school mission is reimaged as equipping difference makers, it suggests moving away from traditional compliance courses and metrics and toward leadership and contribution opportunities–more big problems, fewer right answers, more adding value, fewer year end bubble sheets. More real world learning and fewer AP classes may eliminate a few selective colleges from consideration but it will expand access to new pathways.

The New Pathways (#NewPathways) campaign will serve as a road map to the new architecture for American schools, where every learner, regardless of zip code, is on a pathway to productive and sustainable citizenship, high wage employment, economic mobility, and a purpose-driven life. It will also explore and guide leaders on the big education advances of this decade–how access is expanded and personalized, and how new capabilities are captured and communicated. When well implemented, these advances will unlock opportunities for all and narrow the equity gap. You can engage with this ongoing campaign using #NewPathways or submit an idea to Editor using the writing submission form.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.