The role of the private sector in edu

The WSJ reported that “The US government doled out $502 million for a dozen wind and solar energy projects.” The big winner was Iberdrola, a Spanish wind giant. Coming in second was Horizon, a subsidiary of a Portuguese firm. Third place went to a UK owned firm. These grants will likely result in an energy efficient infrastructure, but two things strike me as interesting:

1. the big winners were all foreign owned, an indication of where public incentives have encouraged private investment over the last decade, and

2. all the grant recipients were for-profit companies, an opportunity that the US Department of Education doesn’t share with it’s $100 billion stimulus.

The education sector bias (and related legal prohibitions) against investment by private companies is remarkable in contrast to other public delivery systems. Innovations in health care, energy production and transmission, and transportation are often the product of private investment in government requested, sponsored, or incentivized project. We don’t mind if textbook publishers update versions, but hackles go up when private operators propose school management. Most of this is just disguised job protection; the rest is historical bias.

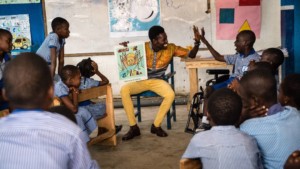

Yesterday I visited Atlanta Preparatory Academy, a new school run by Mosaica, a private charter school operator. After only a month access to an old school building, the place was updated, orderly, and clean. On day two of a new school, it was clear that a common instruction vision and curriculum framework were a guiding force. Classrooms were colorful and organized and featured products of the rich art and history curriculum. A talented principal (trained by New Leaders for New Schools) introduced me a to an amazing teaching staff, some of whom had transferred from a Washington DC Mosaica school. The instructional day was an hour longer than local schools with 12 extra days of school each year.

You’d see the same at a National Heritage Academy, a privately operated network of 70 public charter schools. Mosaica and NHA are offering a service that is clearly superior to near by public schools and doing it for less money. They usually have to provide their own facility with no public funding. Yet they are prohibited from holding charters directly in most states. They find or construct a non-profit corporation which seeks a charter and then contracts with them for school management services. They run the risk of being kicked out of a school that they invested hundreds of thousands of dollars to open.

The $650 million Invest in Innovation Fund (i3) that will soon be doled out primarily to school districts—folks with very little ability to invest in, manage, or scale innovation. Unlike the Department of Energy, public-private partnerships are prohibited. If USED was able to invest half of i3 in private ventures, it would be multiplied several times over by private investment (10x in some cases), it would fund scalable enterprises with the potential for national impact, and the innovation would be sustained by a business model.

The barriers and prohibitions erected against for-profit companies in education weaken American competitiveness. Many of the interesting schools and learning tools are being developed internationally—all with private investment.

This isn’t a hypothetical argument for me. I spent the last year raising money, starting companies, and hiring staff (during the worst recession in 60 years). Worse than the recession are barriers to entry that inhibiting the tools and schools that will mark the next generation of personalized learning.

We send our kids to privately run hospitals, we travel over privately constructed roads, we buy power from private companies. Private sector investment and innovation should play a more important role in American education. Private companies have built-in incentives for speed, quality and scale. Visit Atlanta Prep or an NHA school if you want to see private capital providing a great service for less.

0 Comments

Leave a Comment

Your email address will not be published. All fields are required.